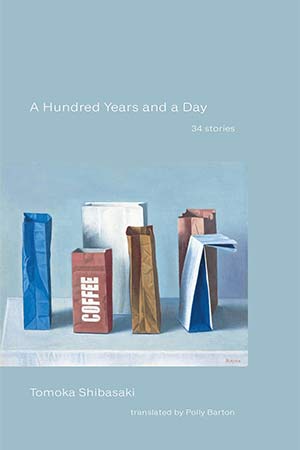

A Hundred Years and a Day: 34 Stories by Tomoka Shibasaki

Berkeley, California. Stone Bridge Press. 2025. 208 pages.

In the thirty-four stories in A Hundred Years and a Day, Tomoka Shibasaki paints a piecemeal portrait of her Japanese homeland, an ekphrastic collection of tales whose spare language and flashing brevity muralize and memorialize Japan—its countrysides and cityscapes, its competing ascent/descent into modernity. The inexorable passage of time haunts every story in the collection: buildings fall, landscapes change, and memories fade. In one story, a river floods a town and evokes the history of the land, rewinding time until the incisions of human activity and presence carved upon the earth are nothing but a distant future, a far-off dream.

Dreams contour the lives of Shibasaki’s characters, whose frequent anonymity belies their idiosyncratic particularity, their yearning humanity. Three young students skip school and discuss escaping their small town; a man moves between rooftop apartments, chasing a vision of home; an avid TV-watcher dreams of becoming an astronaut and, one day, finds her way to the moon. The slice-of-life longings of the collection’s variegated host of characters create a constellation of lives passing slowly and then in a sudden, rushing deluge of minutes, hours, days, years, until time’s surging floodwaters recede. Here, in the dried-out temporal floodplain, appears Shibasaki’s specter of change: the recurring image of a demolished or out-of-use building that was once bustling, thrumming with life. Apartments and temples, cinemas and ramen shops, train stations and shopping arcades—none are immune to crumbling into memory, to disappearing behind the encroaching, effacing sleekness of the modern.

Notably, single-sentence summaries comprise the table of contents, and these brief summaries appear as epigraphs preceding every story. For example: “A ramen shop called House of the Future stayed open for a long time; the other businesses around it vanished, apartments were built, and people came and went.” This rhetorical move insists that the reader know the story, unvarnished and simply plotted, prior to reading the story. This palimpsestic reading process imposed upon the reader creates an unusual yet effective balance between expectation and payoff. The stories unerringly follow their epigraphs but may invert or expand, inject nuance and complexity; the resulting pleasure of reading A Hundred Years and a Day derives from the epigraphic insistence on readerly foreknowledge, which makes the details laced into Shibasaki’s narratives all the more satisfying to discover. To read this collection is to shine a light through Shibasaki’s already-woven web of stories and to see new, surprising, enlightening colors glinting on the filaments. Illumination—that is the power of these stories.

In A Hundred Years and a Day, the quotidian reigns as the significant. Friends come together and drift apart; families gather and disperse; generations pass; legacies arise and unravel. Shibasaki curates a collection of stories that feel at once fragmented and full; demolished, decayed to their now-overgrown foundations; swelling with renewal, returning like the tide; aged and retrospective, mournful and wistful; brimful of unwept possibility.

Alex Crayon

University of Kansas