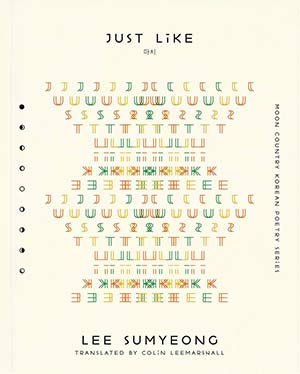

Just Like by Lee Sumyeong

Boston. Black Ocean. 2024. 80 pages.

Amid the endless expanses of our systems, the texts in Just Like are thought experiments that seem to strive restlessly toward decentralizing the primacy of human knowledge. In this precarious historical moment, in which we are beginning to experience diminishing returns on generations of unchecked ecocidal violence, and paired to the ever-impending arrival of machine superintelligence (AGI, viz. the singularity), Lee Sumyeong intuits repetitions everywhere: “into a complex / crying children enter and because the complex spills out // there are so many complexes so / they are living in the same complex.” These are not lyrical poems but instead something arguably far more fascinating: Lee’s existential incredulities defamiliarize language, and, while wholly refusing to judge the mess we’ve made, her book nonetheless steadfastly refuses to avert an epistemologically querulous gaze.

In the foreword, translator Colin Leemarshall suggests that, “like elusive dreams, Lee’s poems are often no more than semi-apprehensible”; certainly, these texts will exercise a reader’s imaginative faculties, though time and again narrative imperatives guide us toward arresting dénouement. Inside grammatically defamiliarized domains—“A man runs a field and the field of the man running the field caves in”—we arrive at surfaces, not depths, irreality amid our absurdly unvarying social structures. As Leemarshall avers, this writer’s style prioritizes “disintegrative logic, isomorphic grammar, surreptitious homophony”; gazing into the spheres, Lee intuits the impossibility of knowing. Her style resolutely and often hilariously works actively instead toward unsettling and unknowing.

Indeed, in the interview at the end of this book, the author asserts a strict anti-anthropocentrism, in which her writing “moves closer towards an attenuation, an abandonment, or even an erasure of the self.” By these means, Lee “instantiate[s] a kind of parity between self and object.” A local version of Charles Olson’s field poetics, then, but with a twist toward attempting “to escape from the abyss of meaning and into surface.” Arguably ecopoetic, Marxian, and posthuman in their inflections, these texts nonetheless hold back from mere critique, and the endgames (indeed, the ethics) of our unshifting paradigms are left largely unexplored. Instead, Lee hopes that “the objects contained in my poetry are sufficiently diverse as to preclude a single interpretive lens.”

In texts where the narrator wants “to cry because there were so many blanks,” Lee’s scenes are always permeable, chaos shifting constitutionally in myriad arrangements, as if a presiding impetus inside this book of textual adventures. At the conclusion of one narrative, readers are told “the village was difficult to know,” and this captures a definitive focus: our systems have worn wonder from the places we inhabit, perhaps even from our minds and hearts. Just Like reminds us just how automated we may have become. This is a book to struggle with, and its profundities cannot be easily framed: were I to be foolhardy enough to make the attempt, I’d venture that Just Like may be a book attempting to rouse its most engaged readers from soporific indifference.

Dan Disney

Sogang University (Seoul)