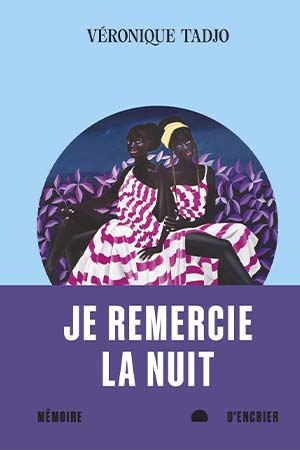

Je remercie la nuit by Véronique Tadjo

Montreal. Mémoire d’encrier. 2024. 303 pages.

With time, the greatest of bards, alone able to unveil how this text—literally without a full stop—will conclude, Je remercie la nuit (Prix Ahmadou Kourouma 2025) is a work of infinite care nursing the life-stories of Ivorians and South Africans, at home, out of place, and in exile, fervently expectant and caught up in the indictment of the consequential turmoil of the nation-states’ twenty-first-century identity politics and graft.

Journeys course the narrative’s trajectory, which opens its first sequence (2010–2011) with a bus journey back to Abidjan, from Korhogo, in the north of the Ivory Coast, where Yasmina had invited her roommate, Flora, to meet her parents and discover her region during their university break between the two rounds of the presidential elections in 2010; and closes it with Flora’s friends succeeding in getting her safely to the airport in time for her escape flight to Johannesburg. The second sequence (2011–2016) follows her as she makes her way figuring out the South African metropole’s own cartographic pulse, guided by the African refugee population of Yeoville, monitoring intently both the political situation back in Abidjan and the fallacies of the postapartheid nation-state.

Character-like, both cities’ scapes inhabit the text—populous, dangerous, scarred, traffic-ridden, and yet proud or alluring, harboring havens among the botanical garden’s trees or Sandton’s eye-popping city mall. Similarly present, the disembodied messaging of the ubiquitous radio and its contemporary social media analog, Facebook, interlock the political protests on and off the university campus in Abidjan with the lives of the two protagonists, master’s students in biology and in francophone literary studies, respectively; whereas in JoBurg, it is the TV at the Maison des Ivoiriens that gives a blow-by-blow narration of the events unfolding in the Ivory Coast alongside emails that keep Flora in touch with her family and friends. Other accounts—voiced, watched, heard, and read—intervene to recount how questions of identity intersect with the history that undergirds the Ivorian civil war and to relate the born-free’s disillusionment with the racialized economic inequities and access to higher institutions of education and to the concomitant violence and xenophobia that haunt South Africa’s transition to a rainbow nation.

Various textual genres, too, register the (language) poles that underwrite the human aspirations and conscience of the times as exemplified by a marketing flyer for “Tagtracking,” listing what to do when carjacked; the framed preamble to the 1955 Freedom Charter that Flora receives as a birthday gift from Xolile, the Sowetan artist whom she falls in love with; and the two first-person emails she finally receives from Yasmina announcing her choice to become her husband’s third wife for the freedom and independence it offers her to resume her studies at the university being built in Korhogo. They stand on the page in italics alongside such passages as the description of Flora’s thesis about the first Ivorian woman writer, Simone Kaya, earning a master’s with distinction at Wits, or her critical appreciation of Xolile’s paintings and her father’s art collection, and together they fulfill the imperative of Je remercie la nuit’s epigraph in bold capital letters: take hold of life, wring fate’s neck.

With spare poetic truths and moralist fables, Véronique Tadjo’s intimate, diary-like narrative arranges Flora’s notebooks to re-present multifaceted viewpoints on entangled histories-in-the-making. Tadjo conjoins reflections on the practices of artists and women authors in the ferocious, spirited hope that this generation of Africans will retain their impatience to break with the past, cross divisive borders, and embrace a relational coming together.

Sarah Davies Cordova

University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee