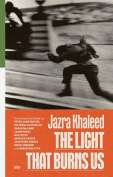

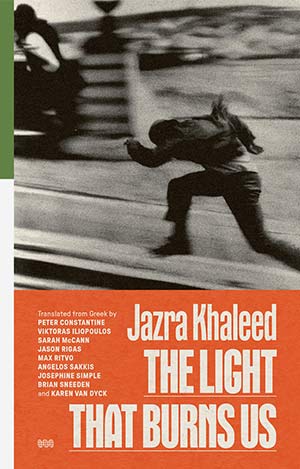

The Light That Burns Us by Jazra Khaleed

New York. World Poetry Books. 2024. 198 pages.

Jazra Khaleed’s second edition of The Light That Burns Us delivers a poetry of protest—raw, unrelenting, and necessary. Translated from Greek into English by a team of notable translators, this collection forges language into a weapon of defiance, introducing a “new poetry” to the English-speaking world. The distinct style of each translator aligns with Khaleed’s interest, as he points out, “in creating poetry through cut-up or collage, threading together texts from various sources, from poems to tweets, from articles in mainstream media, to lines or phrases from antifascist magazines.” Khaleed’s verse “repurposes” poetry into a fiery tool of protest, pulsing with the revolutionary energy of the Arab Spring.

The Chechya-born Greek Poet Khaleed channels the nightmare of the Syrian Civil War and its aftermath in a Greek refugee camp, transformed into a quasi-concentration camp through sheer suffering. This quadripartite collection bears witness to war and exile in harrowing detail. The first section opens with the poem “the war is coming (1),” followed by an epigraph dedicated to Chayath Almadhoun and his million Arab poets, painting a haunting picture:

I decided to leave Syria the day a stray bullet passed in front of my eyes. That day I realized that my homeland was not my homeland, my blood not my blood, and my freedom belonged to a freedom fighter who didn’t think to ask my permission before he shot me: a lack of courtesy we encounter often in wartime.

The recurring theme of war unfolds in three more iterations in this first part [“The War Is Coming (II),” “The War Is Coming (III),” “The War Is Coming (IV)”], warning readers of the imminent outbreak of war, both literal and metaphorical. Khaleed’s verses embody the poetic guerrilla war of a working-class refugee, fighting with stonelike words against racism, exclusion, violence, labor exploitation, hunger, death, and war. This section includes powerful poems set in distinct typography, such as the following in uppercase letters to amplify death and despair: “death tonight,” “somewhere in athens,” “class hatred is growing,” “a jobless man sits on a stone,” “first death of the poet j.k.,” “show peace no pity,” “my body is not a country,” “the light that burns us,” and “gone is syria, gone.”

A self-portrait emerges unlike any before:

Whenever I hear the word peace

I sleep with a gun under my pillow

Jazra Khaleed is my name

A holy whore

a bastard poet

a fighter sometimes, mostly a coward

I know who I am

I have stained the honor of every family

Similes are my strongpoint

I’ve collected curses from every cursed

poet.

Reclaiming his lineage from the poètes maudits (cursed poets), Khaleed is done with poetic decorum. He dares to insult well-established poets, including Nobel laureate Odysseas Elytis, who glorified the sun-drenched Aegean Sea. For Khaleed, the Aegean is “the anus of death,” and Greece’s light is blinding: “greece, what light you waste so that we do not see you.” His rejection of capitalization symbolically dismantles hierarchical structures, while the intertextual reference to Elytis’s famous line—“My God, how much blue you waste so that we don’t see you”—signals Khaleed’s radical break from past poetic mainstream traditions. He scorns traditional poets outright (“Fuck off, flower poets”), calling instead for an incendiary “new poetry (X1000),” a poetry that incites action: “Let’s become a poem / let’s become a beat / let’s become gasoline. / Poetry means this: attack.”

Yet his work is not devoid of lyricism. An unusual lyricism rises from the dirges and incantatory rhythms of “gone is syria, gone,” where anaphora and repetition echo the famous dirge about the fall of Constantinople, “Gone Is the City.” This tragic, bitter lyricism spans the second part of the collection, framed by “The War Is Coming (V)” and “The War Is Coming (VI).” One particularly striking moment captures this blend of poetic beauty and tormenting violence:

“Don’t worry,” said the bullet, “I’ll go in and out.” I explained to her that I couldn’t allow it since when she left she was bound to take some of my memories—like the face of the girl I loved in the fifth grade, the voice of the imam the first time my father took me to pray, the smell of the freshly baked bread in my grandmother’s house, the fingers of my teacher as she taught me to write the word “war” [in Arabic] and Van Basten’s final goal in the Euro of ’88.

These synesthetic memories function like a stasimon in a Greek tragedy—a choral song offering reflection between episodes, allowing the audience to process the unfolding catastrophe. The second part closes with the full irony of “hope has always a plan b,” a long poem structured into fifteen numbered aphorisms that dismantle illusions of hope, culminating in the defiant proclamation: “hope should die so that we can live.”

By the third part of the collection, the “war is coming” motto has transformed. The attacked becomes the attacker. This section, spanning pages 89 to 164, comprises thirty-six vignettes of violence, rebellion, and protest, illustrated by snapshots of riots and uprisings in the city, similar to the book’s cover image based on a still from the film Return to Aeolus Street (2013), by Maria Kourkoúta. Khaleed denounces the erasure of immigrant laborers from history books:

these words are the weight cupped inour palms

the chop just stopped but a new storm

is brewing

it’s war, we just started

my years beached on Elytis shores

like a starving lion living off rage

waiting

as a matter of urgency we must get

hold of and start circulating

an image of the worker-proletariat that

shows him as he really

is “proud and menacing”

my class my pride.

This segment concludes with a composition modeled after Nanni Balestrini’s Blackout (2001), a geometrically chesslike arranged text, encoding the suffering of Syrian immigrants and working-class laborers in Greece. Comprising three tables, each with twelve horizontal and seven vertical columns—referencing the twelve months of the year and the seven days of the week—this semiotic poetic puzzle requires constant decoding. Each letter corresponds to fragments of literature and newspapers on the daily suffering of Syrian immigrants. Through this experimental form, Khaleed rewrites history—exposing, rather than erasing, the voices of the oppressed.

The fourth and final part, “requiem for homs,” is an elegy for Homs, a historic city in western Syria, besieged for three years during the Syrian Civil War. Evoking Dionysios Solomos’s The Free Besieged, where he depicted the unimaginable siege of Missolonghi, this requiem bears witness to Homs’s destruction, ending with a stark realization: “‘Of all the beasts man is the most wild.’”

This is Khaleed’s unabashed new poetry—a poetry through which, as he asserts in the afterword/interview, he has been “increasingly pushing the limits of what is considered poetry in Greece.” With resounding success, I would add. Through The Light That Burns Us, Khaleed does more than push boundaries. He sets them ablaze. Jazra Khaleed’s poetry not only redefines Greek literature thematically and stylistically but also contributes to a global poetics of resistance.

Vassiliki Rapti

Harvard University