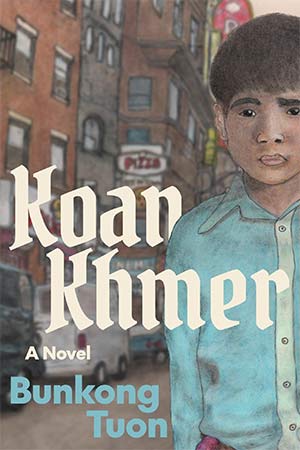

Koan Khmer by Bunkong Tuon

Evanston, Illinois. Curbstone Books. 2024. 256 pages.

Bunkong Tuon’s debut novel tells the coming-of-age story of a Cambodian American writer, Samnang Sok, written in the first person. Tuon’s bildungsroman is divided into four parts: “A Cambodian Family Portrait,” which tells the harrowing story of life under the murderous regime of the Khmer Rouge, the family’s flight to the refugee camps in Thailand, and the sponsorship of an American family in Massachusetts that enabled the family to immigrate to the United States when the protagonist was nine years old; “Surviving in America,” which covers that roughly ten-year period of adjustment in the Boston suburbs, the struggle to make a life, the brutal racism they experienced; “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Cambodian American,” in which members of the family, including Samnang, move to Long Beach, California, where Samnang discovers his passion for writing; and the final part, “Koan Khmer,” in which Samnang achieves his dream of becoming a university professor, in which role he can pursue his goals to write and preserve Cambodian culture for future generations. Each section is made up of short chapters that are more like vignettes or stories. “Stories are my way to suture the wounds of history,” Tuon writes, in the voice of Samnang, in the epilogue to Koan Khmer. Koan, by the way, means “child” in Khmer, the Cambodian language.

Each section is jaw-dropping in its own way. Getting out of Cambodia alive after the chaotic disruption of the Khmer Rouge regime is traumatic. Samnang’s mother actually dies when he is only three years old, owing to the fact that medically trained physicians in their village were all killed by the Khmer Rouge and replaced with peasants who offered bark dipped in honey. Samnang’s grandmother, Lok-Yeay, the family matriarch, carries him on her back through the jungle to the refugee camps.

Life in America is no less fraught. The family moves to Revere, Massachusetts, north of Boston, and is immediately beset by racist violence. At one point, the police come to Samnang’s family’s home in Malden, saying that they need to search their home because some dogs in the neighborhood have gone missing. Sound familiar? It’s an American urban legend that’s followed immigrants all over the world, from Chinese to Haitians.

Samnang feels so alienated in Massachusetts that he even considers suicide. He’s a bright kid, but despite the encouragement of adults both in his family and in school, he turns to skateboarding instead. When his uncle and aunt move to California to open a donut business shortly after Samnang graduates from high school, he goes with them.

His downward spiral continues until one day he has a dream while working the graveyard shift at a cleaning company. He goes to the public library, where he discovers Charles Bukowski, and the whole world of literature opens for him. Dreams are an important motif in Koan Khmer, from a vision of a mermaid in the Gulf of Thailand to the recurring dream of a man on horseback wearing a golden crown. How these all relate to the “American Dream” is a potent theme of the novel.

While this is the story of one man’s coming of age, it would have been nice to learn the fates of some of the other refugee characters in the story, like Bopha, another orphan who is like an older sister to Samnang. Inspired by the suffering she saw in Cambodia, her ambition was to be a doctor, but she drops out of the story in high school. But make no mistake, Koan Khmer is a remarkable novel. (Editorial note: WLT nominated Bunkong Tuon’s poem “How to Defeat Pol Pot” for a 2023 Pushcart Prize.)

Charles Rammelkamp

Baltimore