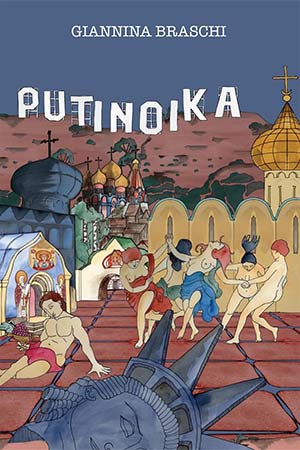

Putinoika by Giannina Braschi

McAllen, Texas. FlowerSong Press. 2024. 294 pages.

From its title, Putinoika, the fourth novel by Puerto Rican writer Giannina Braschi, delivers some of the most urgent literature imaginable. Against the crushing waves of an endless despair-inducing ocean of news, it offers sailing over it in pure textual delight—the here and now of wordplay, the release of hilarious dialogues, a slow reveal of literature as a treatise of epistemology to oppose the banality of evil.

There is the sheer pleasure of witnessing a character called Bacchus talking with antagonists named Melania, Ivanka, and their husband. There is a secret group of women called the Putinas, which infiltrates classical mythology to argue with the Furies to finally push Medea, Antigone, Clytemnestra, and their peers to take charge. The author herself appears under her own name—or masked as Tiresias, Nietzsche, Greta Thunberg, and countless other voices—to savor the joy of calling the president who hates the Spanish language a “Pendejo” a thousand times, simply because he lacks the capacity to recognize when he is being irrelevant in the realm of beauty. “The method of your madness is not precise,” adds the voice of Bacchus, also addressing the fact that this novel was originally written in English with crucial interpolations of slurs in Spanish. “You don’t have what it takes to make humanity tickle again,” as the ancient god of trickery pinpoints to remind the reader that the classics used to be part of a flammable civic debate before being sculpted in marble.

Accordingly, this shapeshifting novel celebrates the grand tradition of seeking wisdom in dark times through the lens of mischief rather than tragedy. The echoes of its title also make its title a paranoica novel, circling back to its obsession with troika. Add to this the layer of the implicit reference to a Russian oligarch’s name—one that, in Spanish, hints at the “world’s oldest profession,” the one you are likely smiling about when reading the title: the profession of dominating while letting oneself be governed by the sum of money.

How does one grasp, in the deep urgency of Braschi’s narrative project, the importance of the old-fashioned word perestroika embedded in the title, except as a denunciation of today’s inability to articulate a collective—nationwide—will for radical openness? A society that once clenched shut like a fist for decades now sees communism, capitalism, and social democracy as interchangeable practices, wielded by authoritarian oligarchic groups for convenience. Can reality be manipulated simply by renaming things via government decree? Is not the act of writing political literature the opposite of totalitarianism—an unstoppable power over reality?

Putinoika defies the logic of weaponizing everything by offering, generously, a deep sense of belonging through the beauty of words—a beauty available to anyone whose only residency papers are this novel in their hands, the possibility to migrate freely into the joy of creation through collective listening and reading. Braschi proposes a strategy for survival in response to the rhetorical aggression of US media and omnipresent power, akin to how Palestinian poetry, Ukrainian fiction, or Boricua reggaetón, confront genocide: before disappearing, let’s take inventory—a palinode of what still makes us happy among death threats, a bacchanalia of what is being taken from us, an orgy with all the materials that once defined what we called the culture of life. “We can’t discover love in the patterns of disintegration of senses and control,” as the character Giannina declares.

“They think it’s all about storytelling,” she says earlier in the novel. “But I say it’s about geometry and architecture.” While Putinoika explores different strategies to deceive power, it also interrogates the nature of narrative itself. In a moment of bot farms, when the political event is a never-ending propaganda rally, the exposed polyphonic nature of Braschi’s book—to the point that it can be read as a theatrical play as well as an essay on freedom—asks aesthetically relevant questions: Is a novel just a monologue that erases the name of its characters, a disembodied stage—which also reminds us of contemporary masterpieces like those of Jon Fosse and Diamela Eltit—a tragedy without resolution, no catharsis in sight, just a constant buildup?

When “language controls thinking process through plot,” liberation of the body in apparent madness seems like the realism of the current era, bringing to the fore the perils of a novel without a story but made of a myriad of fake narratives, in search of voices that can only offer truth when it becomes interrogatory:

I want the manifestation of the thinking process to express itself loud and clear—not to be subjugated to any past tense method but to clear its throat of any method to express its voice—the singing of its voice loud and clear—and the being that has been subjugated to the language—to the citizen—to the nation—to the system—to the method—to liberate itself from the shackles that contain a structure.

If plot is everything, voices are also at risk of becoming mere puppets. Then, Braschi asks, is there such a thing as creative freedom? Her own version of Bacchus responds: “I am pregnant with a chorus. . . . The masses want to become godly.”

At the launch of Putinoika in Manhattan in fall 2024, I raised my hand to ask a question to the author: “Giannina, aren’t you afraid that Putin might read your novel, that his local agents might retaliate against you?” What I witnessed in her response—and this is why she is one of the living masters of Caribbean literature—was how her performance seeks to transcend notions of difference, rejecting literary indifference in favor of a quest for all sorts of universal justice. Following the hidden tradition of the best picaresque tricksters and prophets, her answer captured the zeitgeist as a mystery that everybody understands: “It’s Putin who should fear me. Because what I do—my language, my work, my art, this literature that belongs to everyone—is something neither he nor his Putinos will ever be able to achieve or exploit to their advantage.”

Carlos Labbé

Machalí, Chile / Brooklyn