All the Sublime and Not So Sublime Tales That Make Us: Olinda Beja’s The Shepherd’s House

Olinda Beja was born in the city of Guadalupe in 1946, on the island of São Tomé in the small equatorial archipelago country of São Tomé e Príncipe, a former Portuguese colony. She is the daughter of a San Tomean woman and a Portuguese man living in São Tomé e Príncipe during colonial times. Beja’s writing discusses and celebrates Africa and Europe, exploring the tensions and richness that result from miscegenation and the encounter of cultures. Beja holds double citizenship (Portuguese and San Tomean), often describes herself as a daughter of São Tomé e Príncipe, is regularly engaged in promoting San Tomean culture, and was named a cultural ambassador for the country in 2022. She has written over twenty books in different genres: poetry, short and long fiction, and children’s books. Her creations have received various awards, and several of her children’s books are included in national reading curricula and have been dramatized in schools in Portugal, São Tomé e Príncipe, Switzerland, and Luxembourg.

When she was almost three years old, Beja was separated from her biological mother and sent by her father to Mangualde, in Portugal—the northern interior highlands region known as Beira Alta—to live with paternal family members and pursue her schooling. She was raised by a paternal cousin who became her adoptive mother and was told her San Tomean mother had died. At the age of thirty-seven, Beja met her biological sister (from the same father and a different San Tomean mother), then living in Portugal, who told her that her mother was alive, and that she ought to visit São Tomé e Príncipe, to regain acquaintance with her lost family and cultural traditions.

Beja reflects on coming to terms with a part of herself that had been stolen from her: her bicultural and biracial identity.

This voyage of return is recounted as an engaging saga by the author in her emotional and colorful autobiographical novel titled 15-Dias-de-Retorno / 15-Day-Homecoming (Pé-de-Página Editora, 2007). Beja describes and reflects on her difficult and painful—but also very joyous—stay in her homeland for fifteen days, detailing the exuberant sites, the language, sounds and smells of the island, the unbound love and attention she received from her mourning mother and extended family, who had awaited the return of a lost beloved daughter. All of this—places, sounds, people, the voice of the mother—Beja tells us, still lived in some part of her unconscious, just waiting to be brought to the surface. In this book, she also reflects on coming to terms with a part of herself that had been stolen from her, her bicultural and biracial identity, the racism she suffered growing up in Portugal, and the reasons why she was sent there to live.

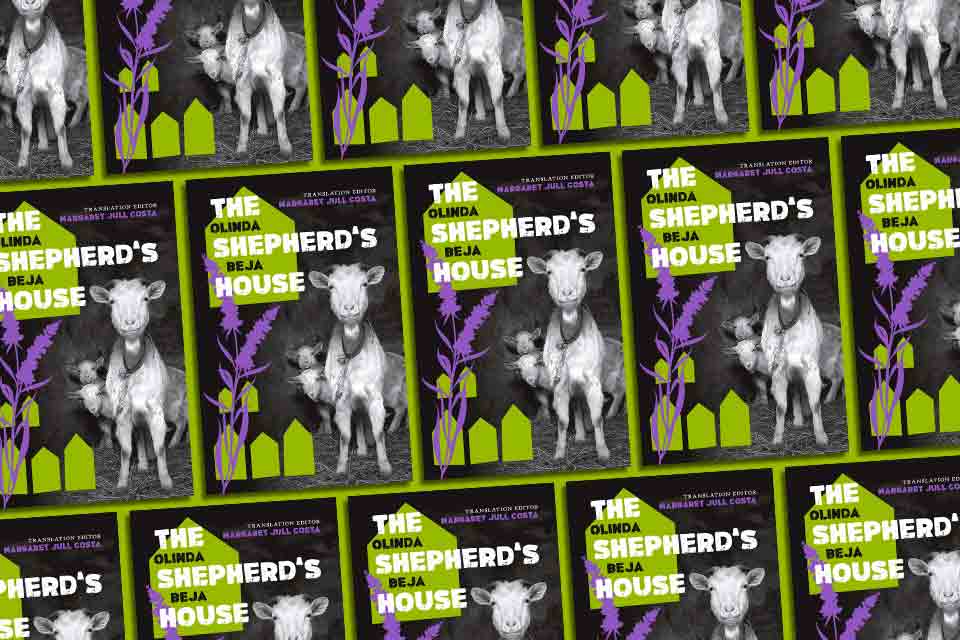

Despite being an undeniable daughter of São Tomé e Príncipe, Olinda Beja is certainly also very much a daughter of Beira Alta—those rugged and twisted highlands in the northern interior of continental Portugal, where she grew up, which possess immense natural beauty and are haunted by the dreams, experiences, and memory of intense human suffering and poverty. Beja’s Beiran genealogical link is explored in the collection of short stories The Shepherd’s House (Arquipélago Press, 2025), originally published as a Casa do Pastor by Chiado Editora in 2011. In this sparkling collection, Beja’s deep love for and attachment to Beira Alta are very present. Despite the cold and despair that she felt growing up in this region at times—a cold and despair born out of the mystery that was her own life, and also the poverty (physical and mental) of a region deeply affected by Salazar’s fascist regime. Beja often felt racism there too, reminding her that she was not quite a daughter of the land. Despite all this, the highlands of Beira Alta hold their own incendiary magic for Beja, constituting an intrinsic part of her identity. These tales of trials and tribulations, of joys and sorrows, of transcendental, mystical, and mythic visions and ways present in The Shepherd’s House will make you love these highlands too.

One of the fundamental objectives of this collection is the preservation of memory—of traditions and professions that have been replaced with modernities. The book presents you with a wealth of fascinating characters who live in the rural settings of Beira Alta, witnessing to ways of life that have almost disappeared. The shepherd João Grilo feels this loss, mourns it, and is thrilled with the idea of having his stories recorded for others to read:

“All my skills are in danger of extinction,” he joked with a sad, ironic smile. “Extinction!” he repeated, with a long yawn like someone wishing he could go back in time. In that bucolic Virgilian setting, João Grilo spoke of his regret in words filled with both indignation and longing, more appropriate to a man condemned to death than a free man like himself. (2)

Olinda Beja’s goal in The Shepherd’s House was to honor the many stories she heard from the old shepherd João Gilo, her paternal (adopted) grandmother Marquinhas, or others, which she herself experienced as a child growing up in Beira Alta. She wanted to give these stories a house where they could live and carry witness of other times, as she notes in the preface: “I brought them all together because it seemed to me that these stories were very lonely. They needed a house full of light and joy where they could hear the chirruping of birds and the tinkling of sheep bells and where all the children of the world, young and old, would be welcome” (xvii).

The translation of the book goes back to 2012, to UK author Anne Morgan’s Year of Reading the World project and her desire to read a book from every county in twelve months. Since she could not find a book translated to English from São Tomé e Príncipe, she put out a call for translators and eventually chose Olinda Beja’s A Casa do Pastor to be translated. The stories were translated by many translators, including, among others, Anne Flecther, Claire Keats, Ana Cristina dos Santos Morais, and the renowned Margaret Jull Costa, who also edited the full collection. There is a sort of irony here: the fact that the content and setting of The Shepherd’s House are not related to São Tomé e Príncipe but rather to Beja’s upbringing in Beira Alta. But it should not matter since Beja is indeed a daughter of many stories, worlds, mothers, fathers . . . As Ann Morgan writes in her foreword to the collection,

Setting wasn’t a decisive factor for me in qualifying Olinda Beja’s narrative for consideration as being “from” a particular place—as British writers have always roamed the globe in their imaginations, I didn’t see why writers elsewhere should stick within certain borders—the focus and perspective of this collection defied easy categorisation. [. . .] “From” is and ought to be a problematic concept. (xii–xiii, xv)

And in actuality, most of us, if not all, yearn to be part of many settings, many nations, many worlds. We yearn to connect, to find meaning, neighbors, and friends—extensions here and there. We are multitudinous. Multinational. We desire to break borders—physical, mental, spiritual, cultural, epistemological—and dance with strange siblings from outer universes. We are from Heaven and Earth, like the boy in the story “The Sower of Stars” who took off one morning with his grandfather, supposedly to work as a mason and build houses, but then decided to ascend to heaven, becoming a sower of stars instead.

We desire to break borders—physical, mental, spiritual, cultural, epistemological—and dance with strange siblings from outer universes.

This desire to expand ourselves beyond our immediate confines, present in “The Sower of Stars,” appears in a myriad of other ways in several other stories of the collection. The characters need the magic of art to combat the bareness of their existence. This desire is iterated by the narrator in the story “Belarmino, the Cow and the Bean Soup”: “Today, I know that the value of a story depends on the magical way it can transport us, because only magic can free us from the heavy burden that life places on our shoulders every day” (28). Like the iconic modernist Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa, the narrator of this story, though a person of humble means and little formal education, also knows that “literature, like all art, is a confession that life is not enough” (“Impermanence – A mesquinhez”). Pessoa is the one who has voiced this statement, but he also seems to insinuate, in the celebrated poem “Tabacaria / The Tobacco Shop,” by his heteronym Álvaro de Campos, that only intellectuals can really feel deep existential anguish. Such insinuation would be misguided.

The need to combat the bareness of existence is present in many other characters in The Shepherd’s House, who, for the most part, are not formally educated. We see it in João Grilo’s tales of transhumance. The beauty, freedom, excitement and joy that such a nomad life entails can be felt in the way he details his experiences to the narrator. This existential need is further revealed in tales where reality and fiction become indistinguishable, or barely distinguishable—the magic appears narrated in the same tone as the real or with little explanation as to why it happens, making this collection slide into the genre of magic realism. This merging of the magic and the real allows for a holistic understanding of existence that goes well beyond the confines of realist writing or pure reason, permitting us to see, understand, and conjure up meanings and ways of being that have transcendental and sublime affiliations—ways that go beyond what the eye can see, and, in that sense, these narrations take us out of the mundane and habitual.

The Shepherd’s House offers readers a multitude of endearing and engaging characters: dreamers, nomadic shepherds, hungry boys who eat bread crumbs and a quarter of a sardine, gluttonous priests, businessmen who are con artists, bandits, witches, dead women who come back to life to work as fortune-tellers, young women who fall in love and patiently await their beloved’s return from the war only to die before their arrival, and other characters that will make you laugh, cry, love, empathize, yearn . . . We are also gifted the sublime natural beauty of the highlands of Beira Alta: the mountain ranges with open vistas and horizons, the genistas, the heathers, the rivers, the fog, the snow, the oak trees, the cuckoo, the doves, the sheep, the goats, the cows, and so much more.

The stories’ tone ranges from magical realism to social realism, the picaresque, children’s tales, and fairy tales (albeit often with unhappy endings), bringing to us a multitude of narrating feats and characters to enjoy and spend time with. We can find in these tales hints of the writing of Miguel Torga or Isabel Allende or even Charles Dickens. This interlacing of tones bestows the collection with tremendous richness and attests to the writer’s versability. The language is often crystalline, possessing a simplicity that brings forward a narrative aesthetic which combines well with the social reality of Beira Alta that it portrays.

Toronto Metropolitan University

Works Cited

Beja, Olinda. 15-Dias-de-Retorno. Pé-de-Página Editora, 2007.

Beja, Olinda. A Casa do Pastor. Chiado Editora, 2011.

Beja, Olinda. The Shepherd 's House. Arquipélago Press, 2025.

Pessoa, Fernando. “Impermanence – A mesquinhez.” Arquivo Pessoa.

Pessoa, Fernando. “The Tobacco Shop.” Translated by Richard Zenith. The Iowa Review, 31, no. 3 (Winter 2001/2002): 75–80.