An Oblique Take on War’s Carnage: Siegfried Kracauer’s Ginster

“When the war broke out, Ginster, a young man of twenty-five, found himself in the provincial capital of M.” He goes out to the town square, where a crowd has amassed, waiting for something. The bright afternoon light makes “a person yearn to take a walk on their heads, which [shine] like asphalt.” All of a sudden, the nation becomes “one folk,” though Ginster never recalls having “been introduced to a folk, merely to individuals, single human beings.” That single folk. As for war, only in school had Ginster heard of it, something that “lay in the distant past and came furnished with dates,” though something that now had people talking about “defending the Fatherland” and “our supreme commander” and not “about important things.”

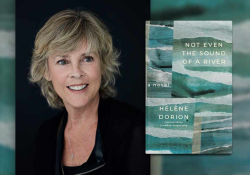

The Ginster in question is the eponymous character in Siegfried Kracauer’s 1928 novel Ginster (subtitled Written by Himself), now available from NYRB in its first ever English translation. The novel follows its titular character over the four years of the Great War (namely, his efforts to stay out of the war), with an epilogue set five years after the war’s end. The novel and its principal character take their name from a German name for the plant commonly called broom or gorse in English, which was also the (apparently disparaging) school nickname for Kracauer (1889–1966) himself. The novel’s mischievous, evasive character may first be seen in this strange choice of name for the protagonist (who, as the “Written by Himself” subtitle would have it, is also author of the text) and in the fact that by the end of the novel’s first paragraph, the narrator has explained that Ginster’s “real name was not Ginster at all.” What that real name is never emerges; and what real might mean for a fictional character with many similarities to his author is characteristic of the novel’s wryly intelligent form of play.

What real might mean for a fictional character with many similarities to his author is characteristic of Ginster’s wryly intelligent form of play.

Ginster’s defining characteristic, and the one that most markedly differentiates this novel from other war novels (perhaps especially All Quiet on the Western Front, which was published the same year), is his desire to remain aloof from life. Soon after the war begins, he travels from M. (a thinly disguised Munich, according to translator Carl Skoggard) to the family home in F. (Frankfurt), where his mother, aunt, and uncle insist “on a livelihood” (since every “human being has a calling, and the first money one earns brings such happiness”). Ginster, though, “would have felt happier if the money were given to him as a present,” and, rather than choose a profession, he “would have preferred to become nothing at all.” Ginster is more than a mere slacker; like Bartleby, he seems to want to opt out of life altogether. Ginster tells one character he “would really like to dribble away to nothing,” and at another point, he thinks to himself that “he would have liked to exist as a gas” because “he could not imagine ever solidifying into something so impenetrable” like conventional men, with their “heavy body masses confidently asserting themselves and refusing to share.”

As one who positions himself outside society (almost as if outside humanity entirely), Ginster perceives the world in a highly defamiliarized way. His landlady in M. “consists of three spheres stacked on top of one another to form the outline of a bowling pin,” and when she laughs, her apron “[lurches] back and forth across her belly like the carriages of an amusement park ride.” Ginster’s perception of other characters often takes this form of jarring comparison, distortion of spatial relationships, and extreme metonymy/synecdoche such that characters become wholly identified with a single feature. The soldiers become uniforms, and when Ginster and his friend Otto visit a pond in a park after the latter has enlisted, Otto’s uniform towers “like a monument over the lonely expanse, out of which [rises] a clamor of frogs.” Indeed, joining up for the war effort “was already desirable for the sake of the homecoming, when the uniforms would celebrate a triumph.” And when Otto salutes passing officers, he does not “swing the arm” himself; rather, his arm “must have been inserted into his body, along with little wheels,” a system “activated remotely, by the uniforms passing by.”

Later in the novel, during an evening outing with members of the intelligentsia, one man’s beard is “transformed into a specially illuminated waterfall like the one at Triberg,” which becomes the man’s single feature, even when eating at a restaurant, where “the waterfall [plummets] into the plates.” This mode of description sometimes alludes distantly to the war’s carnage, as when at a party, Ginster describes dancing as “music and noise [hacking] the human mass to pieces and leaving behind limbs and body parts that really should have been carted away.”

Ginster is ultimately a novel that, by design, resists tidy explanation.

As guides on this literary journey with Ginster of two-hundred-some pages, readers have translator Carl Skoggard’s notes and Johannes von Moltke’s afterword. Kracauer was known in his own time, and to English readers of today, mainly for his writing on film, and von Moltke’s remarks on the cinema of Kracauer’s era, the possible influence of Chaplin (especially the Tramp as a means of comic social critique), and inclusion of still images from the 1924 French experimental film Ballet mécanique are particularly illuminating in thinking through Ginster. It is, however, ultimately a novel that, by design, resists tidy explanation, so the notes and afterword, though quite good, do not solve the intriguing, often hilarious puzzle that is Ginster.

Like the comedy of Chaplin’s Tramp, Ginster’s hilarity is also tragedy, from early in the war, when the eponymous character works at designing a military cemetery (for the “many soldiers who had lived in the city formerly and were prevented once and for all from returning home,” who in life had been housed “along with their wives and children in miserable holes” but will now, in death, “enjoy better quarters”) to the government’s appeals for support of the war effort (asking people “to surrender their copper utensils and their sons for melting down”) and, eventually, to a night in November 1918, shortly after the kaiser’s abdication and the armistice, when Ginster wonders what “sort of war comes now” as he weeps “for his dead uncle, for himself, for countries and human beings.”

Goodyear, Arizona