The Invisible Craft: Rewriting Human Origins through the Botanic Age

Long before I stepped into the dust of an archaeological trench as a professional, I was a student of architecture, mesmerized by the sketches of Altamira and Chauvet. At that time, I didn’t yet grasp the immense, staggering depth of Paleolithic time, but I felt a profound sense of “timelessness” in those images—the same meditative silence I experience today when I work with clay. I often recall the creative gap between myself and my sister, Asal; while she is a born creator, I often felt like a mere imitator of her brilliance. But looking at those cave walls through the eyes of an archaeologist, I realized that thirty thousand years ago, there were no “imitators.” There were only pioneers—the likes of a “Mrs. Chauvet” or a “Mr. Altamira”—who birthed creativity from a place of pure, inward necessity, long before Da Vinci or Picasso ever held a brush.

Long before I stepped into the dust of an archaeological trench as a professional, I was a student of architecture, mesmerized by the sketches of Altamira and Chauvet. At that time, I didn’t yet grasp the immense, staggering depth of Paleolithic time, but I felt a profound sense of “timelessness” in those images—the same meditative silence I experience today when I work with clay. I often recall the creative gap between myself and my sister, Asal; while she is a born creator, I often felt like a mere imitator of her brilliance. But looking at those cave walls through the eyes of an archaeologist, I realized that thirty thousand years ago, there were no “imitators.” There were only pioneers—the likes of a “Mrs. Chauvet” or a “Mr. Altamira”—who birthed creativity from a place of pure, inward necessity, long before Da Vinci or Picasso ever held a brush.

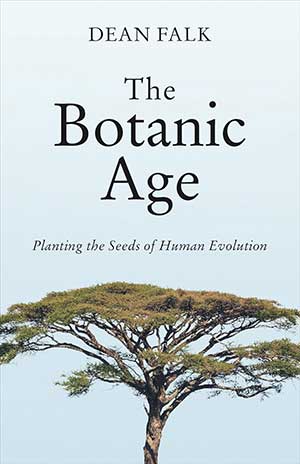

As an Iranian archaeologist specializing in human evolution and gender, I have spent the better part of my career trying to give a voice to these silent, “invisible” creators. In my own published volumes, such as Women and Gender in Prehistory and The Paleolithic Woman, I have argued that our discipline has long suffered from a profound “lithic bias”—a fixation on the durability of stone and bone that has systematically obscured the complexity of ancient life. We have mistaken the survival of flint for the totality of the prehistoric experience. This is why Dean Falk’s latest work, The Botanic Age: Planting the Seeds of Human Evolution (University of Toronto Press, 2025), feels like more than just a book; it is the missing piece of a prehistoric puzzle I have been trying to solve for years.

Falk offers a radical and necessary departure from the “Man the Hunter” narrative that has dominated paleoanthropology since the 1970s. For decades, models like Owen Lovejoy’s have suggested that bipedalism evolved primarily to free the hands of males to carry meat back to “passive” females waiting at a home base. Falk turns this lens upside down, focusing instead on “botanic” technologies: the woven slings, the fiber baskets, and the organic baby carriers. These were the truly transformative tools—innovations likely engineered by women—that facilitated the survival and brain development of our slow-growing infants.

These truly transformative tools—innovations likely engineered by women—facilitated the survival and brain development of our slow-growing infants.

The synergy between Falk’s biological arguments and my own field experience in the Iranian Plateau is striking. In my recent work at the Qaleh Kurd Cave—a site where recent discoveries have pushed the timeline of human presence in the region significantly deeper into the Middle Pleistocene—I have witnessed firsthand the evidence of cognitive sophistication that defies old stereotypes. While the specific Neanderthal remains discovered there, such as the child’s tooth, date back to approximately 175,000 years ago, the site itself hints at a much longer continuity of occupation. As I noted in my collaboration on The Return of Neanderthals, we have consistently underestimated these ancestors. They were not “evolutionary dead-ends” or brutish creatures; they were skillful hunters with complex social lives who mastered the harrowing glaciations of the Pleistocene. Falk’s botanic perspective adds a vital layer to this: if they had the cognitive power to master fire and lithic technology, they surely mastered the “soft” technologies of the botanical world—materials that rot and vanish, leaving us only with a skewed, stone-heavy record of their existence.

The revolution of the human mind wasn’t just carved in flint; it was woven in grass.

In my own books, I’ve often reflected on the “invisible sex” of history, noting that the erasure of women’s roles is often a byproduct of the materials they used. A wooden digging stick or a grass-woven basket doesn’t survive ten thousand years in the soil, while a spearhead does. Falk’s book is a masterful act of scientific restoration. She restores the dignity of the Paleolithic female, moving beyond the tired trope of the cave-dwelling cook to reveal the active engineer. She reminds us that the revolution of the human mind wasn’t just carved in flint; it was woven in grass. It was the “soft” technology of foraging and childcare that provided the high-calorie nutritional base and the social stability required for our brains to expand to their modern capacity.

For scholars and readers in regions like Iran, where we are still striving to modernize our archaeological narratives and move beyond the gendered biases of twentieth-century Western scholarship, The Botanic Age serves as an essential blueprint. It challenges us to look for the “invisible craft” and to listen for the voices echoing from the shadows of our ancient caves.

Falk’s prose is accessible enough for the curious public yet rigorous enough to satisfy the academic mind. This balance is crucial. As a university lecturer, I often see students who are eager for new perspectives but are held back by the dense, often impenetrable walls of traditional texts. Falk breaks these walls down. She doesn’t just offer a new theory of evolution; she offers a tribute to the human spirit—the same spirit I felt as a young student looking at those first cave paintings, realizing that our story has always been one of profound, original, and inclusive creativity.

By the time I finished the final chapter, I felt as though I had paid a small part of my debt to the art and the ancestors I have studied for so long. Falk has given us a mirror in which we can finally see the whole of our species, not just the half that held the stones.

Tarbiat Modares University