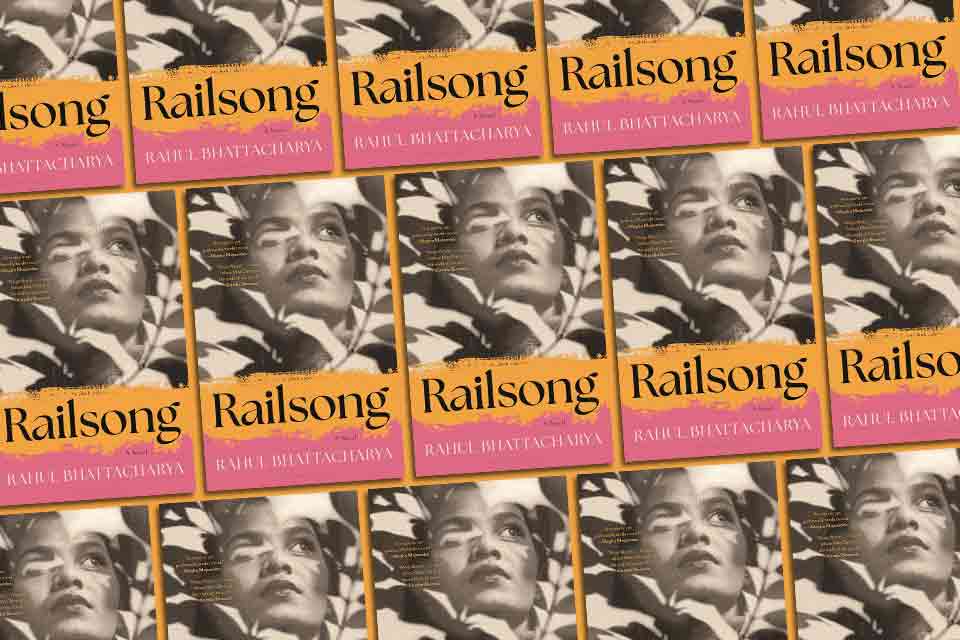

Bombay Dreams: Rahul Bhattacharya’s Railsong

We’ve become accustomed, maybe even resigned, to the long wait for big, new novels from our favorite authors. Kiran Desai’s The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny, at nearly seven hundred pages, was a sensation when it came out last fall, almost twenty years after her 2006 Booker Prize–winning The Inheritance of Loss. Rohinton Mistry, that great chronicler of Bombay, hasn’t published anything since his 2002 magnum opus, Family Matters. We can only hope there’s a new book on the horizon soon.

Rahul Bhattacharya, meanwhile, a journalist and cricket writer raised in Bombay, wowed readers with his 2011 debut, The Sly Company of People Who Care, a sly, audacious excursion into the interior of Guyana. It was a revelation, alive to the rhythms and mysteries of the country’s landscape, history, and people. Now, fifteen years later, Bhattacharya has returned with a follow-up just as astonishing and enigmatic. Railsong (Bloomsbury, 2026) is a sprawling, rhapsodic ode to a changing India in the final decades of the twentieth century, seen through the eyes of Charu Chitol, who from an early age is enraptured by India’s “great railway system whose railsong plucks at our souls no less musically than a sitar string.”

The railway system, clearly, is a symbol of modernizing India, a unifying force that draws passengers from all walks of life regardless of caste, class, and religion. But trains represent something else, too—a sense of freedom and escape. For Charu, who grows up in the small station town of Bhombalpur in the 1960s, the “distant whistle of trains” calls to her, offering a way out. At sixteen, after her mother’s death and seasons of draught and famine and worker unrest, she strikes out on her own. Her destination is Bombay, that glittering, Oz-like metropolis several nights’ journey away.

And yet her arrival at Victoria Terminus is more than she imagined. “The thousands of inhabitants emptied out like a plagued village,” Bhattacharya writes. “Migrants, runaways, their boxes, bedding rolls, slippers, infants, ambitions, compulsions pouring out on to the platform underneath a tremendous roof of steel and light.” Bombay: a stampede of humanity (“a mutiny in every heart”), marching to its own polyphonic beat.

Bombay: a stampede of humanity, marching to its own polyphonic beat.

Before long, Charu falls into step with her colleagues at the Kings & Queens Shoe Emporium, her first job: “Adrenaline coursed through their blood, lactic acid lulled their muscles, freedom sang from their hearts, heaviness weighed upon their souls.” The 1970s will be full of changes, for her and the country. Charu transforms into “Miss Chitol” (her new selves are reflected by her new names in the text). She is hired as an office clerk with the Indian Railways, a dream come true, even as Indira Gandhi’s state of emergency casts a pall over the country.

Nevertheless, it is the internal transfigurations of Charu—or “Miss Chitol” or, after she marries, “Shrimati Chitol”—that is Bhattacharya’s principal subject. Like Kiran Desai, Bhattacharya is acutely sensitive to the travails of the heart and shades of loneliness. Love affairs flare up and fizzle out; Charu continually feels on the cusp of something, though not exactly sure what. She is riven with self-doubt. “Life was a strange and unpredictable journey indeed,” she thinks, “but what exactly was she doing with hers?”

Throughout it all, Charu is accumulating experiences, keeping a record of the people she meets: their backgrounds, histories, struggles, peculiar mannerisms and moustaches. The city impresses itself upon her, molding her into a true Bombayite: “Yet, bit by bit, the Western, Central and Harbour were laying down their tracks across her mind; the tangles of bus routes were lodging themselves like nerves; neighborhoods were mapping themselves on to her brain. She was inching her way up to the city’s eyes to meet them as an equal.”

Charu’s quest for equality, or at least some form of independence, compels her forward. She thrives in her work in the railways’ “sea of bureaucracy,” eventually becoming a welfare officer and traversing the country to file reports from remote locations. It can be grueling and dangerous work—especially for a woman, which her in-laws never fail to remind her. But, for Charu, it’s also exhilarating, liberating. She finds a sense of herself on those long, dusty treks, perched by the window, watching as the 1980s lurch forward and Hindu nationalism begins to gather steam in the distance.

It is the familiar, unremarkable details that are most moving, especially in Bhattacharya’s immersive telling.

Is her life extraordinary? Or is she just one of millions of witnesses to the daily tremors of her time? In some ways, it is the familiar, unremarkable details that are most moving, especially in Bhattacharya’s immersive telling. Charu is achingly alive, fueled by dreams and adrenaline, and so is Bombay. Bhattacharya, like Mistry, is a master at evoking the city’s myriad wonders: the pavement sizzling with scents, monsoon rains, rooftop Divali celebrations. In one crucial scene, the soaring, ecstatic notes of an outdoor concert—like Bhattacharya’s own virtuosic prose—proves transformative. The city keeps churning, the trains keep running—a small miracle in itself.

“Yet watching the trains pull in and out,” Charo reflects, “the crissing and crossing, thousands of people making their way, their hearts in transit, their languages on the go, their origin stories, mythologies and migrations and conquests possibly in stark conflict with those of another, the gods and heroes of one the demons and villains of another, she became vividly sentimental and felt sensationally alive.” Rahul Bhattacharya’s Railsong truly sings.

Queens, New York