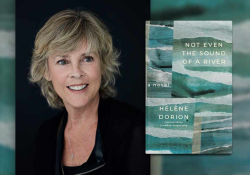

Erotic Alternative Histories: Ally Ang’s Let the Moon Wobble

In Let the Moon Wobble (Alice James Books, 2025), Ally Ang differs from other poets in how far they’re willing to go. For them, a universal subject like love, grief, or dystopia isn’t examined by holding the subject out far. They deliberately bring poetic subjects disquietingly close, and it isn’t a routine-ingénue-appraisal. It’s more inhabiting a concept’s belly, through claimed experience. When Ang pulls their heritage into the room, it is done with such an eye for haunting details, all of which possess greater meaning, much like Toni Morrison and other marginalized writers in the not-too-distant past. Each memory is a pin, deflating former clichés and harnessing the poetic-solace of cultural isolation and its call to us: “How spicy / do you want your food? And my father replies / make me cry.”

Ang’s writing has been called “fresh,” and that’s the simplest way of describing the experience of reading their work, as they question the purpose of humanity when we’ve harmed each other and the unerring world so completely; their final conclusion of whether we’re worth bothering about, returning us to love. Anyone queer will find a portion of themselves in Ang’s ability to speak to queer-love in such intense proximity, as the poem “Nobody Owns My Pleasure” conveys: “my blood shining, wet, no / body owns my pleasure, not even me.” Maybe because they’re not affected or pretentious, nor trying too hard, the writing lands as naturalistic but conversely dreamlike and occasionally achingly beautiful, such as the poem “Beginning with You and Ending with Everything”: “You make me soup with sweet potato / and lentils to soften my stools. So this / is it. I marvel every time I am undone / by another disgusting display / of devotion. This is what love asks / of me: to accept every gesture of care / no matter how humiliating it feels.”

Simultaneously simple and able to slay hard through the rarely admitted truth that most of us find accepting love challenging. Ang’s stories are like a play with minimal direction, allowing themselves to unspool and proffer their honest conclusions. While anger, angst, fear, and grief may create a rageful voice at times, what I took away reading Ally Ang was how nuanced their understanding of human nature was and how they’re able to mine humanity’s depths from a queer, multiethnic lens, which, until recently, was an almost invisible perspective. Yes, today it may appear ubiquitous, but that’s like assuming the gay district of the largest town is representative of a whole state. A trans or queer person remains a target, a social oddity and still unsafe. Ang is able to verbalize this without it dominating the quality of their other messages, which is a finessed art. When they say “who are you without performance?”, it’s a daring question for right now and this claiming of right now’s voice.

What I took away reading Ally Ang was how nuanced their understanding of human nature was and how they’re able to mine humanity’s depths from a queer, multiethnic lens.

The erotic, pared-down observations breathe life into alternative, neglected histories. Whether we’re considering the unanswered questions of the clever poem “The Truth Is” or, conversely, querying whether we should speak it, in “I’m Ashamed to Say It Out Loud,” there’s a consistency of courage and bare-bones acute observation that transcends ordinary brevity. Perhaps that’s patronizing, given that many startling writers have often been young. Perhaps it takes a “fresh” voice in terms of identity and how that translates into language to poke holes in any status quo and offer an actual new way of seeing the same things.

It would be easy for the unkind to dismiss Ang as another woke trans writer, as those facile labels negate the depths of their politics. It is not a stereotype to write poems called “More Americans Believe They’ve Seen a Ghost Than a Trans Person”; it’s a lived hardship. In “Kubaran Cina Bintaro,” Ang evidences their ability to tease equal meaning into a poem’s heart:

The house crumbles into ash like a body

crumbles into ash. What will be left? Kakek,

after everything has burned?

Again, simplicity pulls out organs and lays them next to the unknown languages and ghosts in Ang’s family. Uniquely the experience of the BIPOC, queer, and immigrant/first-generation writer, where location and identity cannot be taken for granted or always known. Though I have read poems on all these subjects before, it isn’t sufficient to say Ang’s contain an alacrity and nuance setting them apart. Moreover, this is a hybrid location of difference, which the general world does not understand.

The doctor

asks if I have a boyfriend, if he treats me nice

while she spreads my legs.

Earlier in this poem, Ang admits “I lie / like I always do” when asked how many sexual partners they’ve had and what gender. This isn’t purposeless obfuscation—this is the lived history of queer, BIPOC, and trans people, though nobody outside those groups will really understand the shame evoked by seemingly normal events like pap smears. Ang is talking about control, how historically, and even now, vulnerable, marginalized populations do not possess it. They take back a lot of that withheld control through their brightening truth.

Grasse, France