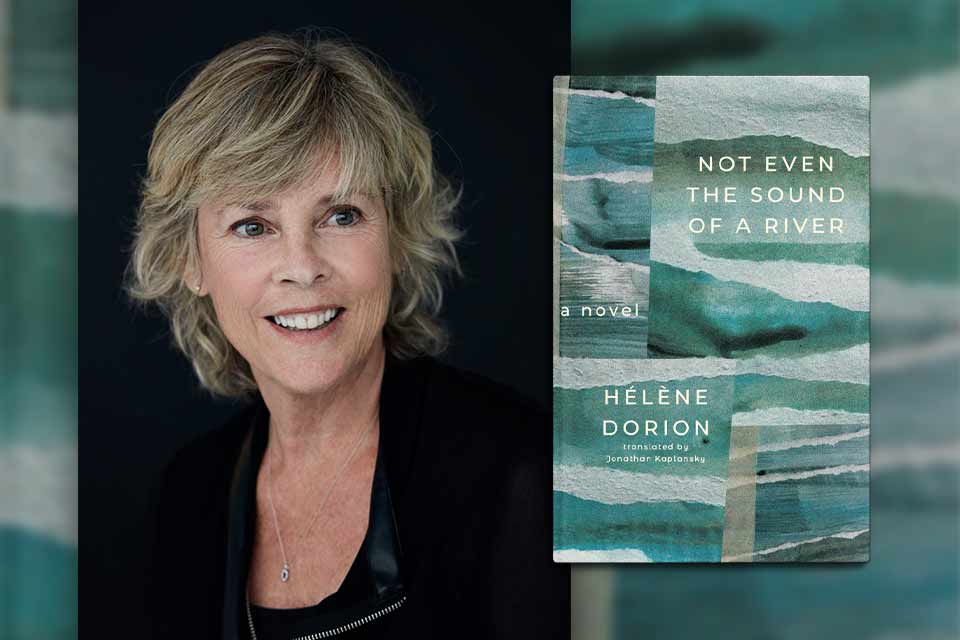

Long-Buried Depths: Hélène Dorion’s Not Even the Sound of a River

Hélène Dorion is a major figure of contemporary French-Canadian literature. Foremost a poet, she is known for her deep connection to the Québécois landscape, its forests, winds, sands, and waters. The fluidly elegiac Not Even the Sound of a River (Book*hug Press, 2024), is her fourth prose work; it is the second brought into English by Canadian translator Jonathan Kaplansky, whose deft style ebbs and flows with Dorion’s long, expressive sentences.

Not Even the Sound of a River interweaves the stories of writer Hanna (secretly a poet) and Juliette, her painter best friend, with the stories of Hanna’s mother, Simone, who has just passed away, and the cold, steady flow of the Saint-Lawrence River. Women’s lives in this novel appear fragile—one husband rapes his wife and impregnates her before starting to cheat on her systematically, another beats his wife regularly—and yet women are the survivors, the ones who hang on and tell their stories.

Part of the book is a reflection on how past suffering can be expressed: Who holds the pain of the past, and how can it inform our present? “We doubt,” Hanna writes, “and that’s what pushes us to explore, to let our gazes drift to welcome along our way what arises, the little wonders that transform us.” The novel’s artists (stand-ins for Dorion herself as poet-writer) struggle to understand and do justice to the tragedies that link people to the land.

Part of the book is a reflection on how past suffering can be expressed: Who holds the pain of the past, and how can it inform our present?

The title of the novel in French is Pas même le bruit d’un fleuve—which translates exactly to the English title, except for the lovely word “fleuve,” which refers to a specific type of river: one that opens into the ocean. And in the context of Quebec, it can only be one “fleuve”: the Saint Lawrence. The title contains a definite geographical point de capiton hundreds of kilometers long, both an anchor and a question mark: the river is, after all, not even producing a sound.

Dorion’s fiction begins when Simone swims out into the Saint Lawrence, an embrace of and by the frigid waters from which she returns to the shore, disappointed. The rest of the novel sets out to understand her will to abandon herself to the great river, her silence as well as the river’s. “Writing does not repair rifts, it only opens the paths needed for us to reconcile with them.”

Dorion’s novel commemorates the very real May 1914 sinking of the Empress of Ireland, one of Canada’s worst maritime tragedies; following a foggy nighttime collision, the Empress lost over one thousand of her passengers. Peeling back layer after layer of forgotten history, Hanna and Juliette recover the names of the victims and find connections that carve out the narrative space for scenes from Simone’s youth. The novel never clarifies who has access to Simone’s memories—whether they are in fact Simone’s, or whether they are narratives reconstructed by the writer Hanna in an attempt to understand her mother. But they give us access to Simone’s long-ago love for a man mysteriously linked with the Saint Lawrence, a man who liked to sleep in his anchored sailboat, out on the waters of the gulf, in all types of weather.

Hélène Dorion’s lyrical voice guides us along the shore of the broad estuary, then across its breadth—south shore, north shore—finally leading us, gently, to face its long-buried depths. “Absence has changed into an expanse of blue to never again close.” If we can be patient in our attempt to write the past, the novel suggests, the landscape will reveal it to us in all its tragic beauty.

University of Oklahoma

Editorial note: Alice-Catherine Carls's review of the French edition appeared in the Summer 2020 issue of WLT.