Repentance and Moral Reckoning: Akiyuki Nosaka’s Grave of the Fireflies

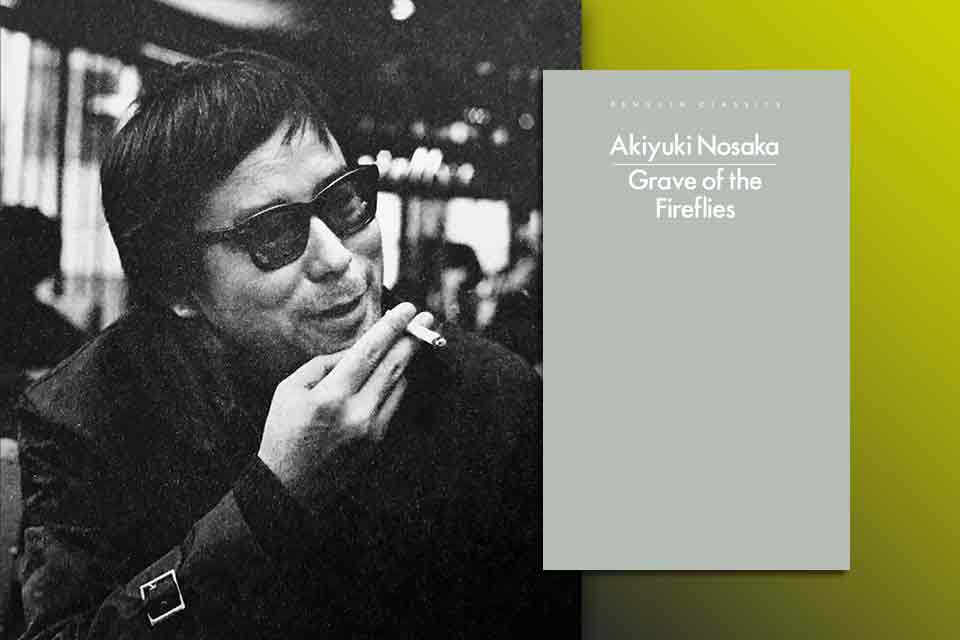

Akiyuki Nosaka’s (1930–2015) semi-autobiographical short story “Hotaru No Haka” (Grave of the Fireflies) is a searing portrayal of war, hunger, and the desperate struggle to survive. Drawing on his own experience of a harrowing wartime childhood, Nosaka crafted a devastating narrative.

“Hotaru No Haka” has appeared in several forms and gained considerable attention. The story was first published in the literary magazine Ōru Yomimono in 1967. It was awarded the Naoki Prize in 1968, sharing the honor with another of Nosaka’s stories, “Amerika Hijiki” (American Hijiki). The first English translation, by James R. Abrams, appeared in 1978 in Japan Quarterly under the title “A Grave of Fireflies.” The tale gained international renown through its 1988 Studio Ghibli anime adaptation directed by Isao Takahata, though the original short story remains comparatively little known in English. Finally, a new, refreshing translation by Ginny Tapley Takemori was published by Penguin Classics in September 2025.

Nosaka had a remarkably diverse career as a fiction writer, essayist, lyricist, singer, and politician. His debut novel, Erogotoshitachi (The Pornographers) (1963), marked the beginning of his success as a writer.

Nosaka’s early years profoundly influenced his work. In Grave of the Fireflies, Nosaka presents a semifictionalized account of these experiences. He grew up during Japan’s aggressive militarist expansion, beginning with the 1931 seizure of Manchuria shortly after his birth. He lost his mother during childbirth, and his father subsequently distanced himself. He was adopted by his maternal aunt and uncle, who later also adopted a baby girl named Keiko.

Japan descended into all-out war in the Pacific after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. In 1945 the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) intensified its campaign against Japan with two major operations: the incendiary raids codenamed “Operation Meetinghouse” and the mine-laying campaign “Operation Starvation,” which effectively strangled Japan’s shipping and supply lines. Entire cities were incinerated in Operation Meetinghouse and similar firebombing attacks, and civilian deaths rose into the hundreds of thousands. Indeed, the cumulative firebombing deaths (around 300,000) far exceeded those caused by the atomic bombs, which were estimated at 210,000 by the end of 1945.[i] The charred streets of Kobe after the firebombing of the city by the USAAF, along with the widespread hunger and despair of wartime Japan, form the backdrop of Grave of the Fireflies. To quote Nosaka, “The air raids, the burnt-out ruins and the black-market trade made me what I am.”[ii]

The story follows two siblings—Seita and Setsuko, who are based on Nosaka and his sister—as they lose their parents and struggle to survive in a city reduced to ruins. Keiko was only sixteen months old during the events that inspired the story, but her fictional counterpart, Setsuko, is depicted as a four-year-old, while Seita is fourteen, Nosaka’s own age at the time.

The narrative functions both as wish-fulfillment and an act of mourning.

The narrative functions both as wish-fulfillment and an act of mourning. Unlike Seita, Nosaka was not the devoted, self-sacrificing brother the story depicts. He claimed to be a war orphan for years and remained deliberately vague about how his sister had died of malnutrition. It was only after the birth of his daughter, Mao, that he revealed the truth. When Mao reached Keiko’s age, an old sense of guilt resurfaced, prompting Nosaka to publish a series of recollections between 1966 and 1967. In these, he recounted the actual events as they had happened—including how he mistreated his little sister and devoured the food meant for both of them.

Grave of the Fireflies offers the reader insight into the hardships Nosaka endured. He witnessed terrible devastation during the raids on Kobe and throughout the war. Unlike Studio Ghibli’s anime, the book goes into the minute, nightmarish details of a ravaged earth and the erosion of humanity.

In the story, Seita and Setsuko personify a heartbreaking loss of innocence. After their mother dies and their home is destroyed, the siblings are taken in by an aunt. The arrangement soon deteriorates as her resentment toward the children grows. She considers them a burden, especially Setsuko, and the siblings find themselves unwelcome in their temporary home. Eventually, Seita and Setsuko move into an abandoned bomb shelter, where they capture some fireflies: fragile, luminous creatures symbolizing the transience of life and a faint, ultimately doomed hope. The consequences of their isolation spiral downward to an inevitable, overwhelming conclusion. Ultimately, this story highlights the unimaginable reality faced by countless children who perished and suffered—not only during the war but also in its catastrophic aftermath.

Reflecting years later on his real-life experience, Nosaka would later write, “Children suffer most in war. The expression on the faces of famished Nigerian children, Jewish children in Auschwitz and Vietnamese children was no different from that of my sister who died of malnutrition” (qtd. in Stahl). The trauma, hunger, and the animal instinct to survive had transformed him into a selfish, even cruel, youth. For Nosaka, writing Grave of the Fireflies was more than a reconstruction of his own past; it was an act of repentance and moral reckoning. Fiction is used to reveal the human cost of decisions made by those in power and to question how survivors should live with what they did to survive. In “Milepost of Hell: On Receiving the Naoki Prize,” Nosaka observes that the book was the product of a deep sense of guilt.

For Nosaka, writing Grave of the Fireflies was more than a reconstruction of his own past; it was an act of repentance and moral reckoning.

Translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori to engage contemporary readers, Grave of the Fireflies remains an enduring story. Takemori’s translation is set apart from the earlier version by Abrams in her handling of the dialogue. She doesn’t try to replicate the quirks of Nosaka’s Kobe dialect (or “Kansai dialect” as Abrams mentions in his translator’s note), favoring a more contemporary prose that feels entirely natural to an English-speaking reader. In addition, she avoids replicating the stream-of-consciousness style that Abrams tried to translate in his work. Instead, Takemori splits the sentences, making the story easier to read without losing its urgency or the “breathlessness” of the original prose, as she mentions in her translator’s note. Takemori provides a fresh voice that will resonate with modern readers while maintaining the story’s timeless essence. The story is essential—if challenging—reading for adults and young, though perhaps too intense for younger children, and this new edition would be a valuable addition to any library.

The current translation has been published exactly eight decades after the end of the Second World War. As technology continues to evolve and advance, the scale of human casualties also rises, particularly in a world where intense conflicts still break out with alarming frequency. Grave of the Fireflies serves as a reminder that war’s true cost is always measured in civilian lives, especially those of innocent women and children.

Kolkata, India

[i] Mark Selden, “American Fire Bombing and Atomic Bombing of Japan in History and Memory,” Asia-Pacific Journal 14, no. 23 (2016): e1.

[ii] David C. Stahl, “Victimization and ‘Response-Ability’: Remembering, Representing, and Working through Trauma in Grave of the Fireflies,” in Imag(in)ing the War in Japan (Brill, 2010).