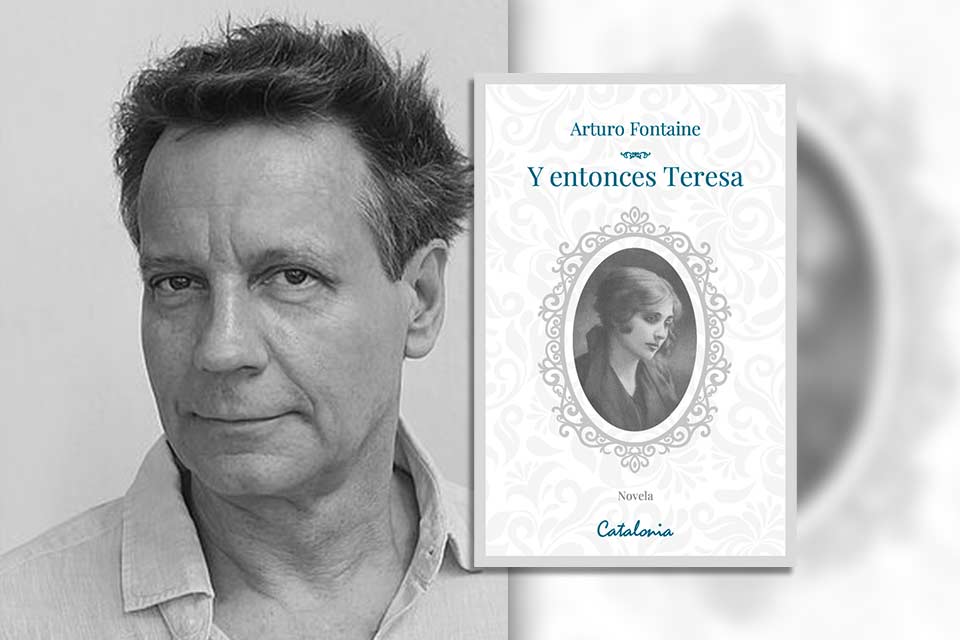

The Incoherence of Love: Arturo Fontaine’s Y entonces Teresa

In Y entonces Teresa (And then Teresa) (Catalonia, 2024), Arturo Fontaine (b. 1952) questions the need to dismantle myths, suggesting it is more valuable to draw on collective and personal heritage. He advocates novelizing events from archives, chronicles, and especially letters, as shown in the novel’s fourth part, which describes a cemetery romance with restraint, emphasizing metaphor over overt psychoanalysis. These and the diaries (written in the convent where she was locked up for “adultery”) are reliable sources. The real Teresa Wilms Montt’s documents “caused a huge scandal . . . because of their intimacy, as they were erotic. So, Teresa was punished as a writer,” Fontaine told El País. She was no Saint Teresa of Ávila, and when she reads The Interior Castle, one senses that she is not interested in chastity belts, stating that “for me, everything is mystical flesh.”

The section “Joaco” (based on the prolific memorialist Joaquín Edwards Bello) emblematizes the tensions between Wilms, her lover “Vicho,” and the society that oppresses her. Her personality is no less complex than that of the prominent men who surround her. There is elegance and compassion here, as if his most recent novel were reorganizing a life he did not design, delving into historical records and scattered works to weave a tale of courage, self-determination, and faith. Without depending on forms of revivifying Wilms Montt motivated by affection, generosity, or sympathy, he opts for novelistic imagination.

For devotees of her mythology, Wilms Montt remains willingly disappointing, deceitful, unknowable, prodigious, and fickle.

For devotees of her mythology, Wilms Montt remains willingly disappointing, deceitful, unknowable, prodigious, and fickle, like many forerunners. She and her fictional double were not Anna Karenina, Emma Bovary, or Mother Teresa, so she soon escaped from the convent, aided by the avant-garde poet Vicente Huidobro. Several women populate this novelization, especially Pauline, defined by her loyalty to the central character. Throughout the novel’s six parts, aesthetics consistently provide intellectual support for the protagonist, yet its influence is confined to her internal reflections. (In her day, she was not the influencer she could be today). Beside the Latin-American avant-garde of her day, she lived la vida loca and la dolce vita before it became commonplace to lump them together. Today, her “licentiousness” would make few people bat an eyelid.

Fontaine does not play with the neuroses of his readers or protagonists. Rather, he hints, “Watch out, even though you know what will happen to these characters, I will keep you turning the page,” and there is no shortage of premonitions about the outcome. Like the opening part in Santiago, the initial sections of the part set in Iquique offer an elegant, natural style with pointillist descriptions and a balanced rhythm that support the unfolding drama. The sections function as character sketches, medical records, literary opinions, or journalistic commentary; although at times the effort to be believable is conspicuous.

Obviously, Fontaine is not the narrator, but the lovers’ discourse he mimics is so accurate that it will dazzle readers with fixed ideas about the language of love, in the sections where the voice is Teresa’s, or in the final pages of the sixth part, where the conciseness of the conclusion of her life and Vicho’s is admirable. Fontaine incorporates or reimagines both historical personalities—such as the politician Arturo Alessandri and the Spanish feminist Belén de Sárraga—and literary figures like Valle-Inclán, Juan Ramón Jiménez, and Gómez de la Serna as well as, during Wilms’s Paris period, Jean Cocteau and Max Ernst, who were central to Latin America’s French-influenced elite.

Because genuineness constantly eludes the characters, questioning where reality lies, Y entonces Teresa is one of the most brilliantly controlled novels I’ve read.

Because genuineness constantly eludes the characters, questioning where reality lies, Y entonces Teresa is one of the most brilliantly controlled novels I’ve read. As an urban legend or fairy tale (she has been called an “anarchist feminist”), the character of Teresa Wilms carries the burden of nonliterary prophecy, the possibility of surrendering to the presumptions of the future. Fontaine’s is not a “biofiction” (a term used by other reviewers that limits his scope) that emphasizes, not without some philosophy, intense erotic desire and suffering; rather, it analyzes the arrogance of trying to manipulate destiny. If the first part introduces key figures, the novel’s final sections are biographical and based on historical records. Jorge Cuevas, a close associate, describes Wilms Montt as someone who resisted categorization, often questioned established norms and stereotypes, and demonstrated both rebellious and conservative tendencies.

There is no problem with fictionalized biographies of women “unsuitable for young ladies,” recovering them from cancellations, or discovering them as daring writers—the case of her contemporaries Gabriela Mistral (whose Los sonetos de la muerte Wilms mentions), Teresa de la Parra, Magda Portal, and María Luisa Bombal, or later Josefina Vicens and Alejandra Pizarnik—in which the storytelling splits between truth and plausibility, making the narrative seem excessive at times. Fontaine, who explains his approach in the preface “Before Beginning,” has written another unique novel, skillfully assessing how to distance himself from the historical facts and psychological conditioning often attributed to Wilms Montt. Although Y entonces Teresa makes the conservative last century more interesting, this is ultimately a nontraditional love story. The fifth part, in which Wilms is cloistered (there, like her mother-in-law, the real machistas are the women), is a wonderful account of the letters between her and Vicho, tense with his escape plan, with caricatured moments and her opinions about men.

The overriding impression is one of diligent and elaborate ingenuity, which gave Wilms Montt her authority, a power with which she was unable to confront her psychological wounds, although in her poetry (some of which has been translated into English and French in this century), she used those wounds to transform them. Fontaine’s great talent lies in revealing this progression, in not turning his novel into a recovery of a fetishized author still little known outside Chile (in 2023, a Spanish edition called Obras completas was published, and individual works have been recovered) or in showing the similarity of different worldviews, but rather in a reflection on the incoherence of love, a global tension in which no represented class rules.

San Francisco