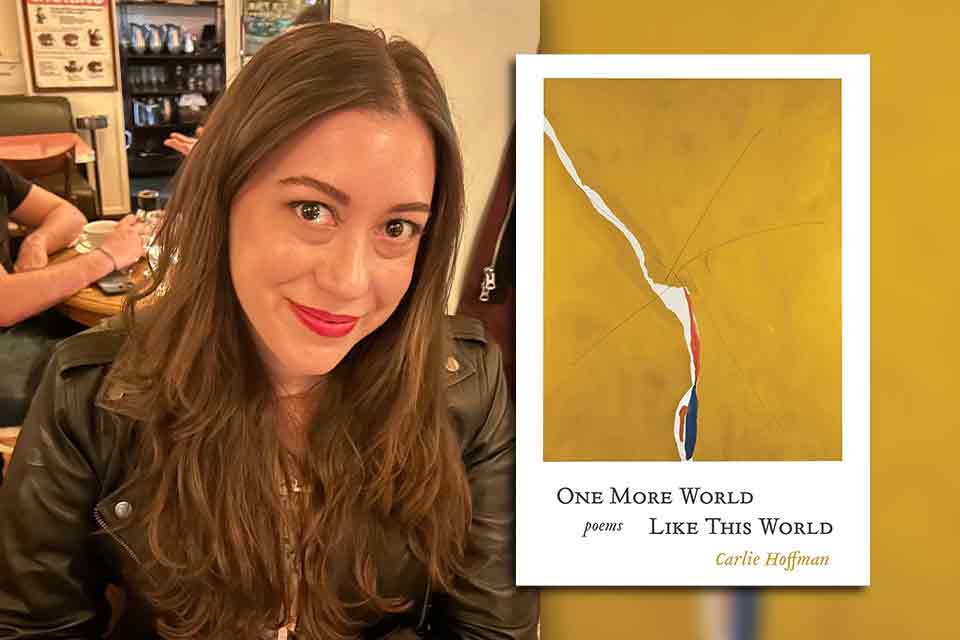

Emotive Pictures: Carlie Hoffman’s One More World Like This World

I have never been able to hear music in my voice so much as I have in reading the lyrical wonder of One More World Like This World (Four Way Books, 2025), Carlie Hoffman’s third poetry collection. To read her poetry is to sing this song of another, so brilliantly is the meter placed; and importantly too, as you hold the words on your tongue. Across three parts, One More World Like This World evokes arresting questions of how women have been squished to fit what the narrative needs from them and asks how they may have just yet retrieved a line for themselves to call home—regardless of which hand holds the pen.

Young to poetry, I often question myself, a standing outsider from the lines as I attempt to make sense of them. However, with Hoffman’s work, I could not help but fall into the richness of her imagery—at once enamored by the power of the speaker in “A Condo for Sale Overlooking the Cemetery in Kearny, NJ,” who grows beyond the swell of the “life on her hands” to consume it: “swallow[ing the light] / [and] demanding a better song.” This poem particularly is compelling, the opening piece from the first section, The Garden, for how it works to contend with Eurydice’s original narrative, pulling her from the flat page and granting her substance—the autonomy of choice in story by saying that the listener “must imagine [her] happy.” Yet there is an ironic tilt working beneath the surface of the line, rippling out concretely with the rest of the work, as Hoffman states that “hell, too, / is an industrious world: round.” There is a dichotomy between the space each takes up, and here in Hoffman’s redress of Eurydice’s narrative, they have a give-and-take, and she “g[iving] something to herself,” rather than being robbed of it.

It is as if Hoffman uses her lines to paint emotive pictures that rely upon remembrance, dragging up the anger or loneliness a listener carries with them unheard, and underscores the truth of that feeling by connection through the speaker.

It is as if Hoffman uses her lines, these specific words, to paint emotive pictures that rely upon remembrance, dragging up the anger or loneliness a listener carries with them unheard, and underscores the truth of that feeling by connection through the speaker. In “At the CarMax in Maryland to Sell Your Used Civic That Doesn’t Have Air Conditioning but Was Your Grandmother’s and the Only Place You’ve Ever Owned,” Hoffman writes:

You love rain when there is none.

You hate November with its dying sun.

. . .

You love this car though it’s gone bad.

Bad like an apple.

Bad like your blues.

. . .

Sign here, says the salesman.

I’m giving you all I’ve got.

There is no one way to feel grief and therefore no tidy way to capture every person’s understanding of mourning. However, Hoffman bridges that distance by blurring it, and again, rhythm works as a key invitation into immersion.

Hoffman’s continual usage of “you” creates a staccato mantra connection—almost like a ticking clock. This meter drives an insistence on time passing, and Hoffman’s use of punctuation and syntax drives the tension by bringing the reader to a halt with each full thought and making them stew on it. Yet there is also a building of intimacy within the listener as we all but become the speaker. The most arresting piece for me was coming to comprehend the abstract, as Hoffman weaves together lines that paint a verbal picture for big feelings, such as this absence here: “rain when there is none,” or a season’s “dying sun.”

The layering of the everyday and the profound is a hallmark of Hoffman’s voice.

The emotions of these images demand that the listener draw in the weight of this feeling so that they may understand the totality of it. Yet the slight irony returns with the mundane setting—a car dealership—which stands in sharp contrast to the emotional magnitude of what’s being surrendered. The car is not merely a vehicle, just as Eurydice’s hell was not as lifeless as once foretold; Hoffman transforms the two into vessels of memory and identity—here, heritage. This layering of the everyday and the profound is a hallmark of Hoffman’s voice.

In reading One More World Like This World, I felt that I was being given the right to join in on the recasting of the narrative: to take it on as our own without any effort on my part beyond allowing the distance to fade. That is a beauty of Hoffman’s writing, a tone of toeing the line between contending emotions, our own irony of arresting rage and mournful melancholy, that these poems conjure to act as an answer to the question why and it shouts, I see you. I, too, have felt that, deeply, but could not figure what to call it: “but it is not language / clearing the landscape / of what I’ve known,” as the poet ends “Ode to the Sudden Forgetting of Your Grief.”

Wilkes University