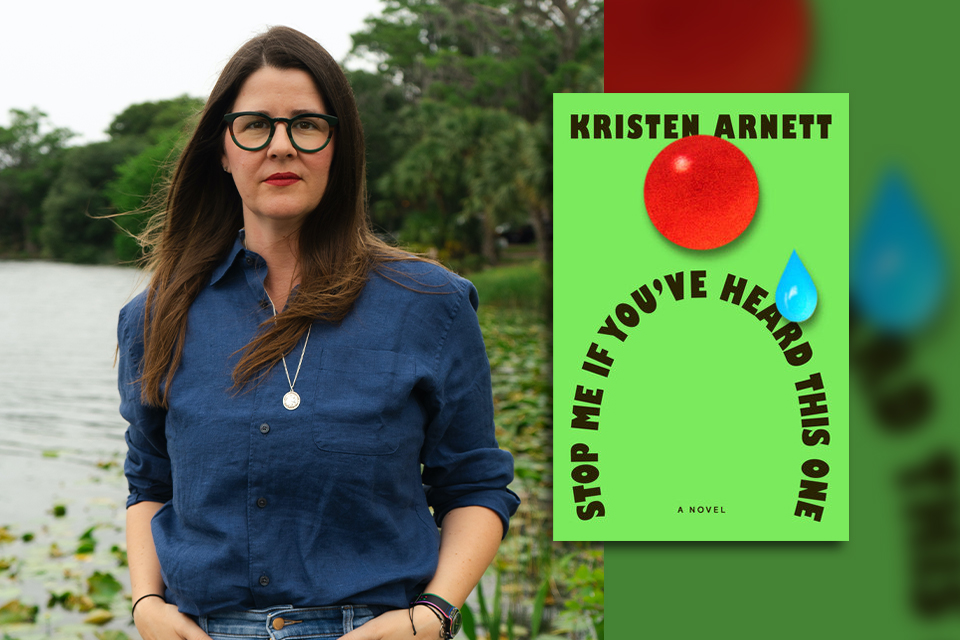

Finding What’s Hiding Underneath: A Conversation with Kristen Arnett

I encountered Kristen Arnett’s work soon after the publication of her debut novel, Mostly Dead Things, when I picked it up in a bookstore. I was immediately arrested by its premise: a woman picking up the mantle of the family taxidermy business after her father’s death. But after reading it, the things that lingered with me were the sense of humanity that underpins the bleak landscape of the protagonist’s grief and the masterful attention devoted to the process of taxidermy itself, which drives the novel into metaphorical spaces where death, the body, and dissection all take on resonant meaning.

Arnett’s latest novel, Stop Me if You’ve Heard This One (Riverhead, 2025), examines the craft of clowning with similar acuity and depth. As its protagonist, Cherry, navigates financial and personal strife as a freelance clown in central Florida, she also demonstrates devotion to her art, breaking down the mechanics of humor and performance in every area of her life through incisive, unforgiving self-examination. I spoke to Arnett on Zoom about her research process for the book, the power dynamics of queer sexuality, and the emotional cost of creating art.

Debbie Ou: Your new novel features a clown, and your debut novel is about a taxidermist. Did the research process differ for this book?

Kristen Arnett: Yes, absolutely. Each book requires its own writing practice, and the same is true for research. For my first novel, Mostly Dead Things, I did a lot of very heavy research. I needed to know the tools that a person would use; I was reading a lot of old manuals. I was going into chat forums where I learned stuff that I wouldn’t have learned reading a manual or googling things. Like, “If you really want to get an eye to look right, you just use Windex.” This is something you only learn from people who actually do these practices sharing information with each other. So it was a lot of in-depth lurking around, seeing people talk, and watching how-to videos.

For this book, I quickly learned that the research is based on my protagonist, because it’s not about what Kristen is interested in. What does Cherry care to learn about? Cherry is kind of a know-it-all about humor and clowning; she’s going to know just enough to get by. So I didn’t want to know too many practical facts. I spent time watching a lot of videos of clowns performing, because clowning is such a deeply physical act. I needed to know about how a body falls, how a body moves to maximize humor for an audience.

I spent time watching a lot of videos of clowns performing, because clowning is such a deeply physical act.

This one video was very nineties—a guy who looks like a youth group pastor is talking really seriously in a suit jacket and jeans—and he’s talking about how a person would slip on a banana peel, talking it through like how somebody would teach you how to do a dance move. Very serious, very practical, dry. And then he says, “Okay, now that I’ve talked you through it, we’ll bring the clown in.” The clown comes in and performs the act; he just slips on the banana peel and then leaves. I think Stop Me if You’ve Heard This One feels incredibly physical because it’s Cherry metaphorically tumbling through the book. She’s very physically fumbling through the trajectory of each chapter. The research was based in the body.

Ou: It’s so interesting to hear you describe that video, because it reminds me that behind every art, artists are trying to break down the process step by step. Is there a reason you feel drawn to write about jobs that a lot of people find peculiar or even a little off-putting?

I’m really interested in anything that people have strong opinions about. I’m a Florida writer, and people have a lot of strong opinions about Florida.

Arnett: I’m really interested in anything that people have strong opinions about. I’m a Florida writer, and people have a lot of strong opinions about Florida—people who don’t even live here or haven’t really been or, if they have, only as a tourist. And people think about these kinds of professions through the lens of tourists. People have a lot of opinions about taxidermy without ever having done it or without knowing any information about it. People have a lot of opinions about clowns, and some are very intense, right? People have a very real fear around clowns, but these people probably haven’t interacted with a clown. They’re basing their opinions off pop culture, social media, things like that. And so I thought, What is it like to be making art for people and they think what you make is tacky or inherently frightening or not funny? I think I’m drawn to characters who are othered in these ways. What’s the flip side of this coin? What’s the thing hiding underneath? That’s what interests me in fiction.

Ou: I didn’t think about the fact that clowning and taxidermy are both creative endeavors that are perhaps not acknowledged or validated by the wider arts community. Cherry even makes the point early on in the novel that many people don’t just think clowns are weird—people despise them. Of course, she’s also a queer woman in Central Florida. She almost seems to revel in the hostility she faces from other people. Recently I’ve been thinking about the intimacy of hostility and confrontation, which I find terrifying because you’re faced so intensely with other people’s desires and fears. Is that something you were thinking about as you were writing the character?

Arnett: I do think that since Cherry is thinking about herself as a performer in every aspect of her life, she needs to be able to pivot for the audience. She might be interested in pushing buttons or envelopes, but she doesn’t want to get her ass beat all the time, right? That’s a very real fear for her. So she thinks, How am I able to make art that doesn’t result in me having violence put upon me? How do I need to speak, act, look? But there are also times she’s not going to be able to de-escalate. I think Cherry’s the kind of character who thinks, This is who I am, so I just might get harmed. I’m willing to be conflict-driven. But even though she is very loud and can be confrontational, she’s not confronting some things because she’s using humor to deflect what she actually needs to talk about—like her relationship with her mother or her friendship with Darcy, which ends up exploding because she doesn’t do what she needs to do. She’s making a joke instead.

Ou: On the subject of intimacy, the book begins with a scene depicting sex between Cherry and a client of hers, a mom who has booked her for a birthday-party gig. It feels very transactional, part of a performance she’s putting on as Bunko the Clown. And when she has sex with the magician, there’s also a similar transactional—or at least conditional—element to it. What do you think Cherry feels about intimacy? Is she choosing to occupy a world where sex is transactional and intimacy is limited, or is she trapped there?

Arnett: I think it’s a question of what people think of queer sex and power dynamics. The opening of the book is this sex scene between Cherry, who’s dressed as Bunko, and a mom who has a clown fetish. The mom has hired Cherry to be a performer, but Cherry also gets off on the fact that this is an older mom because Cherry has a fetish for older women. So, they’re both getting something out of it.

The magician chapter in the middle of the book is the only chapter in which the POV changes. It’s focused on Margot, this mysterious, sexy, much older magician. Margot is in control, so Cherry has very little control. She doesn’t get to touch in the ways she wants; she doesn’t get to extend the sex act. It’s over when the magician wants it to be over. In writing those scenes, I wanted to be very specific about how they looked on the page, so it would mimic who had the power in the situation. Because that’s also a big part of eroticism: who has the power and who’s giving it up.

Ou: It makes a lot of sense that you were thinking more explicitly about power, because Cherry seems like someone who’s very attuned to that. She’s also focused on her relationship with her art, seeming to suggest at times that it’s not altogether healthy. At one point she tells us that “the clown is my id, greedy and impatient and uncaring of the mess it might make in its quest to get off a good joke.” This makes me think about the idea that what art demands from its creator is not limited to what is easy to give. While you were writing about Cherry’s relationship with art, were you also thinking about your own?

Arnett: Yes, I think this is a great question, because so much of this book is about what it is to be an artist and to give everything to making art. And I think that’s not limited to clowning—with writing, for instance, how much does it consume you? How much do you give it? When you make a thing you feel says something of significance, how much of you is required? I think that’s true for me, but I think it’s true for any kind of art. And I want this book to be thinking about capitalism. What does it literally cost you to make art? What does it cost you spiritually? What does it cost you in terms of intimacy and friendships and family? So yes, I was very much thinking about writerly practice, but I was also thinking about every other kind of artistic practice, like dancers who have strange relationships with food and their bodies. We’re all fumbling through, trying to figure out the right balance of art and lived life.

So much of this book is about what it is to be an artist and to give everything to making art.

Ou: Another observation Cherry makes about craft is when she marks a distinction between stand-up and clowning, asserting that stand-up is about the “I” rather than the “You.” Do you think there’s a difference between art that is and is not rooted in identity or the presentation of the self?

Arnett: When we make art, our fingerprints are on it, right? Even if we’re writing away from the self, ultimately it has to come through us as the conduit. If we think about art as a crime scene, if the police show up, they’re going to find our fingerprints on it in some capacity, no matter what we’re making. To bring the question back to Cherry, this twenty-eight-year-old thinks, “I know everything there is to know about clowning and humor.” Saying stand-up is about the “I” and clowning is about the “You”—that’s one small way of looking at how artistic practice functions. But it can be extrapolated further. Clowning is very much about reading the room and trying to give the joke that’s going to be right for that audience, whereas stand-up is—generally speaking—a standardized set that’s honed and practiced, but it’s performed to get the maximized laugh from an audience. These things are functioning the same way, just through different avenues. I think that’s applicable to other kinds of artistic practices.

Ou: You’ve been referencing Cherry’s personality a lot. I was really interested in her as a character because she seems self-aware at times, but there are moments in the novel that indicate she has blind spots, too, perhaps big ones. For example, at one point, her mother’s girlfriend accuses her of not paying attention to her mother’s life. Is Cherry perceiving the world clearly?

Arnett: This is something I very much think about when I’m working on a novel: things we know versus things we think we know. And parent-child dynamics are fascinating, because parents have expectations about how children will behave, but children also have intense ideas about who parents need to be or how they’ve failed. You get a lot of information from Cherry throughout the book about exactly who her mom is. So I didn’t want Cherry’s mom to directly say, “Here’s how you didn’t see me correctly.” I wanted an intermediary to say, “You know, you’re kind of self-involved. Your mom has her own life, too.”

Everybody has ways in which we think we know exactly how something is and how this person is. But that’s not the other person’s lived reality. So anytime I’m writing characters, I really want that to factor into how things happen. Because I do think so much of human revelation is, “Oh, I thought it was this way the whole time, but this person experienced it a completely different way.” That's the most interesting thing to me.

Ou: Do you think writing in the first person allows you to explore those limitations of perspective?

Arnett: This novel is an incredibly voicey, close first; it’s a lot of interiority. You’re really in Cherry’s brain. My second novel, With Teeth, is third person, but I would say it’s an incredibly close third; you’re getting a voicey third from Sammy, the protagonist. I supplemented the perspective with interstitials between chapters and sections, a paragraph from somebody who’s outside of the family who would say—in third person—their perspective on a moment of interaction with the family. It’s totally possible to do all these things in different points of view, whether third or first.

With Stop Me if You’ve Heard This One, it had to be through interactions with others, but also maybe Cherry says something so strongly that you’re like, Hey, wait a minute. What does this actually mean? Is the joke covering up something else? Or are you waxing philosophical about clowning as a way to not talk about this other thing? I feel like that’s the most exciting part about writing something: uncovering the ways the person is lying to themselves or not telling the whole truth.

May 2025