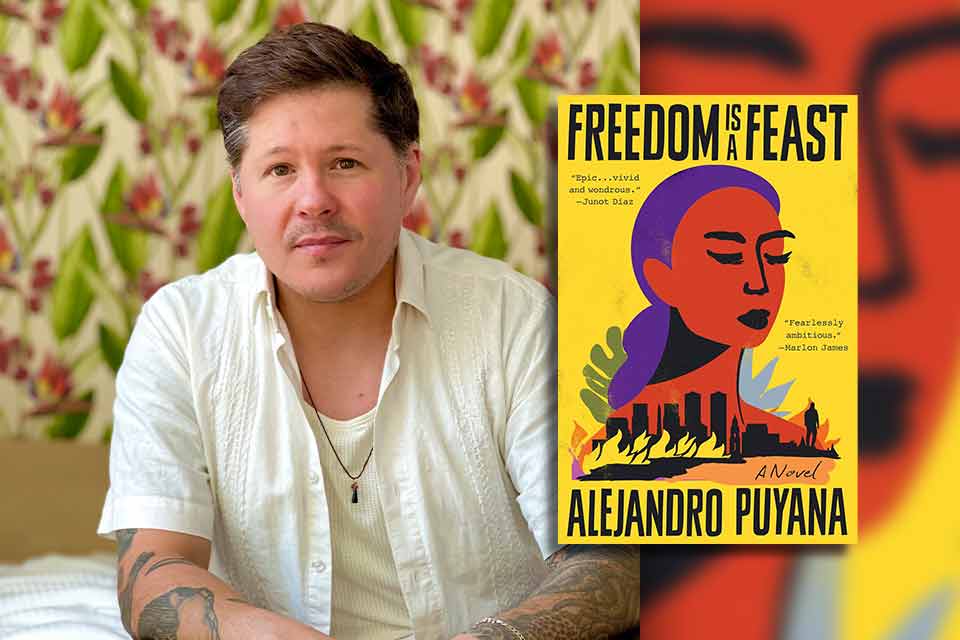

Telling a Complete and True Story of Venezuela: A Conversation with Alejandro Puyana

Alejandro Puyana didn’t anticipate his debut novel, Freedom Is a Feast (Little Brown, 2024), coinciding with daily headlines about deportations of Venezuelans from the US. Yet he is intimately familiar with the strife that has led many, including his family, to leave the country.

A multigenerational epic, Puyana’s novel opens a wide lens into how the last half-century has created today’s Venezuela. Most of the book’s cast is just trying to get by day-to-day, and Puyana is keenly aware these are the people who often pay the highest price for injustices perpetrated by those in power.

His novel, however, also includes a protagonist inspired by a family friend with a larger-than-life story. Stanislavo joins a guerilla movement against the dictatorship in the 1960s, escapes imprisonment, founds an influential newspaper, and befriends Gabriel García Márquez.

I corresponded with Puyana about writing a novel whose cast of characters presents a wide range of ideological perspectives, some of which deviate far from his own. The paperback edition of Freedom Is a Feast comes out on August 5, 2025.

Geoff Graser: After the prologue, your book begins in 1964. Why did you decide to start at this point? How did you research the political climate and history of that time period?

Alejandro Puyana: The first pages I wrote of this book—well over ten years ago now—were set in 2013, through the point of view of Eloy, a young man in the process of committing a kidnapping. But as I kept writing the book and expanding its cast of characters, I realized that the novel wanted, among other things, to tell the story of the rise of the modern left in Venezuela—to answer the question: “How did Venezuela get to where it is today?”

In order to answer, I had to go to the 1960s. The Cuban revolution had shaken the world, especially Latin America. It had inspired thousands of Venezuelans to stand up against a new version of American imperialism, more subtle than before, masked by consumerism and a promise of modern comforts.

The Cuban revolution had inspired thousands of Venezuelans to stand up against a new version of American imperialism.

I had grown up hearing stories of that time, told by my father, including many stories about Teodoro Petkoff (a guerilla fighter, turned USSR dissident, turned presidential candidate, turned renowned journalist), who was a close family friend. His real life became a very loose template for the ’60s portion of the book, or at least a launching point for me to explore the ideology of the time. He was a prolific writer and journalist, so I had a lot of material there to lean on, but I also watched a lot of Venezuelan documentaries recounting that era. Several books interviewing the protagonists of the Venezuelan revolutionary movement of that time by Agustín Blanco Muñoz were also helpful.

Graser: In a prior interview, you said Emiliana is one of your favorite characters. In one scene, the young woman visits Stanislavo, who’s recently escaped from being a political prisoner, to tell him she’s pregnant with their child. How did you manage to write this scene with such tenderness and sensitivity?

Puyana: It was such an important moment in the novel. When you are learning to write, teachers and craft books always stress the importance of characters making choices. Here was a scene where both Stanislavo and Emiliana are forced to make a choice that will dictate the way their life will look moving forward.

Stanislavo is in hiding and has no idea that Emiliana is pregnant. Emiliana has gathered her courage and gone behind the back of the movement’s leadership to tell Stanislavo and give him an opportunity to come with her. They both love each other. They both want to do what’s right. And they both fuck it up.

I didn’t necessarily set out to write the scene with “tenderness and sensitivity,” but I did feel it necessary to explore both characters’ humanity to the fullest. They are in conflict against each other in this portion of the book, but they are also battling themselves. I think the power of the scene lies in the fact that the reader can understand both of them, and the choice each of them makes, and still be left heartbroken that they couldn’t make it work.

Graser: How much do you think Stanislavo fears raising a child during the uncertain times of an authoritarian government?

Puyana: I think part of him is terrified of raising a child, period. But Stanislavo is not a coward. His choice of turning his back on Emiliana has less to do with his fears of being a father and more with walking away from the movement, from the captured friends he’s promised to help. He genuinely believes he can do both. But Emiliana knows that if she allows him to do that, she and her daughter will always be secondary, and she won’t allow herself to be put in that position. In the end, pride sinks them both and what they could have built together.

Graser: In a previous interview, you spoke about the challenge of writing characters with political perspectives different from your own. Can you elaborate on that challenge and maybe give an example and how you overcame it?

Puyana: Look, I think Chávez, and certainly Maduro, have been the worst things that have ever happened to Venezuela. Our country is in shambles, and yes, one can argue that US interventionism has played a large role in that, but for decades the Chávez/Maduro regimes have sunk Venezuela, allowed for corruption to run rampant, and made themselves billionaires many times over. Almost eight million Venezuelans have fled in the process, making it the largest displacement crisis in the world. But Chávez came to power in 1998 in a wave of overwhelming popular support. He spoke to people in our country in a way that no one had ever done.

Almost eight million Venezuelans have fled in the process, making it the largest displacement crisis in the world.

I knew that to tell a complete and true story of my country, I had to find the hope that Venezuelans felt every time they saw someone like Chávez, so full of promise, capable of transforming the country for the better, speak directly to them. There’s a scene in the book where Emiliana and María go cast their vote in the first Chávez election, and they bring little Eloy along. It’s one of my favorite scenes in the book and one of the only scenes where Emiliana and Eloy are alone together, grandmother and grandchild. Even though they are in the act of bringing Chávez to power, something that would irrevocably change the history of Venezuela forever—inarguably for the worse—it was such an easy scene to write. It felt natural to fall into the sense of optimism that reigned during that time for the great majority of Venezuelans.

Graser: Eloy is Stanislavo’s grandson. He ends up in prison as well, but for far different reasons than his grandfather. At what point in writing this character did you realize that he was gay and how much this identity could put him in danger? Have you written or imagined the scene of Eloy talking with his mother about his sexual orientation?

Puyana: I didn’t discover Eloy had feelings for his friend Wili until deep into the first draft of the book. There’s a scene when Eloy and Wili are in prison, and Eloy, who’s a talented artist, sketches his friend. Wili is napping, and Eloy gets a pencil and paper and starts to draw. There was a sensuality in the scene that surprised me—the way Eloy noticed his friend, took him in. It made me look at their relationship in a different light.

It’s not like I made a decision at that point that Eloy would be gay or anything, but it opened a different side of him that I had not expected when I started to write the book. I let that side of him flourish as I kept writing.

By the end of the first draft, that part of Eloy was still there—it was subtle, but it became clear to me that Eloy loved his friend in a romantic way. In subsequent drafts I worked a lot at fine-tuning the way those feelings became apparent on the page, and also what it meant for Eloy to have to hide that side of him, not only because of the stigma being gay may have on young men, especially in a Latin American cultural context, but also the real danger it posed to his life and his well-being in a place like prison.

As for your second question, I know in my heart that Eloy and María talk to each other about Eloy’s sexuality. They talk also about Wili, about how much he meant to both of them. I don’t think I’ll ever write that scene, but I know for sure they both are at peace with all that.

Graser: Wili, Eloy’s best friend, grew up without parents who could support him. He recalls the street kids from your story “The Hands of Dirty Children,” which was included in Best American Short Stories 2020. As an adult, Wili is involved in a life of crime. How important is portraying this aspect of life in Caracas?

There are so many lines in Venezuelan society.

Puyana: Vital, I think, for this book. There are so many lines in Venezuelan society. There’s tremendous injustice. Where you are born, the color of your skin, how you are raised—it all slots you into an expected role and position in the hierarchy of the country. I wanted to portray how easy it was to fall into these roles. There’s a moment in the book when María is looking back at the way she raised Eloy—he was going to college when he commits the crime that eventually sends him to prison—and she thinks herself stupid for having believed Eloy was no longer in danger of falling ill to the “pox of Cotiza men” (Cotiza is the neighborhood beset by poverty where they live). And then you see the family María works for, the Romeros, and how impossible it would be for their children to go through what Eloy did.

Editorial note: Alejandro Puyana is a juror for the 2026 Neustadt International Prize for Literature. His book recommendations, “The Beauty of Debuts,” appeared in the September 2024 issue of WLT.