Preserving Memory: A Conversation with Julie Masis

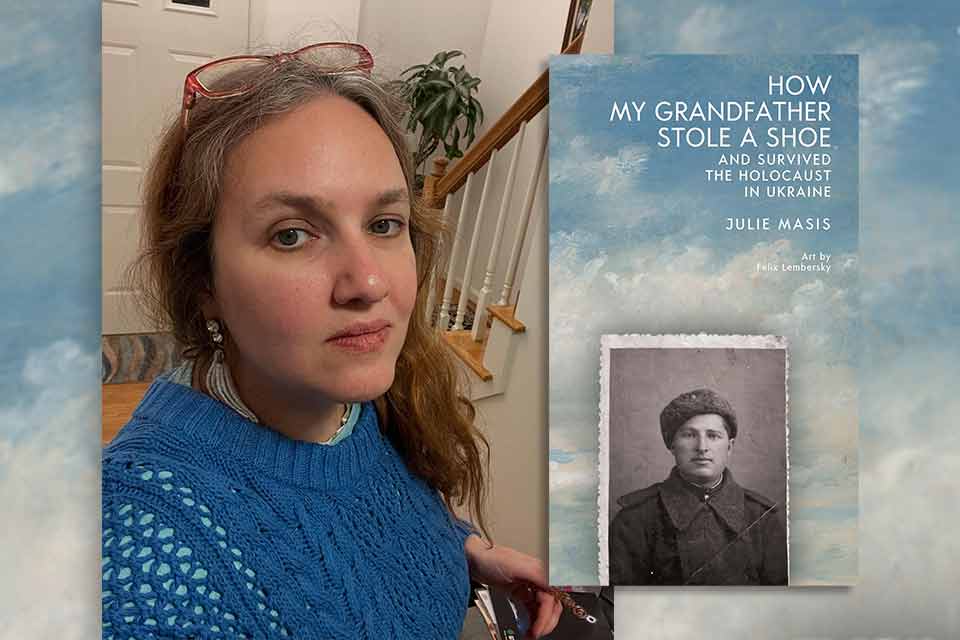

Julie Masis is the editor and publisher of the Russian Boston Gazette, a newspaper for Russian-speaking immigrants in Boston. She is also a freelance journalist who has written extensively about Jewish history. Her stories have been published in the Times of Israel, Jerusalem Post, Boston Globe, Christian Science Monitor, Montreal Gazette, Globe and Mail, and in other newspapers and magazines. She has taught English to Buddhist monks in Cambodia, organized tours to the Khmer Rouge tribunal, and is currently learning to ice-skate. Julie holds a degree in international development studies from McGill University and speaks, reads, and writes fluently in English, French, and Russian and can get by in Khmer. Her book How My Grandfather Stole a Shoe (And Survived the Holocaust in Ukraine), published by Academic Studies Press, has just been released.

Susan Blumberg-Kason sat down over Zoom with Masis to discuss her new book, her journalism, and her years in Cambodia.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: Congratulations on the publication of your book, How My Grandfather Stole a Shoe (And Survived the Holocaust in Ukraine), which tells the story of how your grandfather Shlomo escaped death more than a few times. I love how he said he wanted to survive World War II to find out who won. He seemed so full of life and humor. Do you think his humor helped him live through such grueling circumstances?

Julie Masis: I think so, but my dad has more of a sense of humor than my grandpa. My dad is absolutely talented when it comes to telling stories, and usually they’re stories from real life. The way he tells them makes sad things funny, so it’s funny and sad at the same time. One time after my great-aunt Lisa passed away here in the US—she was ninetysomething years old—we were having dinner and remembering her. All of a sudden the phone rang and people asked who was calling. My dad said it must be Lisa calling us. And everybody started laughing. It was a way of using humor to deal with a really sad situation, to get through it.

Blumberg-Kason: Do you think that’s a Jewish thing? It seems like a lot of Jewish humor takes dark situations and makes them into humorous ones.

Masis: I don’t know how much it was Jewish, but it was also Russian. Russian humor is very different from American humor.

Russian humor is very different from American humor.

Blumberg-Kason: Your grandparents were from Moldova, and during World War II they were sent to a ghetto in Transnistria, a part of Ukraine that was controlled by Romania. Before I read your book, I’d never heard of Transnistria or the Jewish ghetto there in Obodovka. It just goes to show there are still so many Holocaust stories that have yet to be told. What were your main reasons for writing your book?

Masis: Well, my main reason was just to preserve other people’s memories. I have a really bad memory. Sometimes I don’t recognize people or I don’t remember what they told me last time I talked to them. So when my dad started coming home in the evening and telling stories, retelling what he heard from grandpa during his lunch hour when he visited, I felt like I had to write it down. If I didn’t write it down, the story would just disappear.

It’s oral history, and that only stays for as long as people are alive or for as long as they remember, so that’s why I wrote it down. I also didn’t know about Transnistria or the role that Romania played during World War II. I didn’t really know that they were on Hitler’s side or that their attitude toward exterminating the Jews was different from the German approach, and that thanks to that, my grandparents survived. I’d never read a book on that topic. When I recently gave an interview to the Jewish Museum of Moldova, I asked if there have been other books written about the Holocaust as it pertained to Moldovan Jews, and they told me no. I think this book had to be written for that reason.

Also, sometimes history is told based on what we think should have happened rather than what really happened, in the sense that all Germans are bad and all Jews are good. But in reality, every person is an individual and every story is unique. It was interesting that a German soldier helped my grandmother survive in the camp. Also, I didn’t try to present my grandpa as a perfect person. He just told it like it was, like the story about him stealing a shoe.

Blumberg-Kason: I wanted to ask you about the shoe! There’s a chapter in your book that is also your book title. Can you talk a little about that story and why you chose it to be your title?

Masis: I wanted something catchy and bizarre to pique a reader’s interest. I’m working on another book about my other grandpa, and I want to title it How My Grandpa Fell from an Airplane, which is also a true story. I just wanted something that would catch people’s attention. During that time in 1941, shoes made a difference between life and death. My grandpa said that they fed his whole family for a month when he exchanged those shoes for a bag of corn flour later on. He took one shoe when someone left it behind. He got the other shoe because he saw someone with it and he told a police officer that it was his shoe. It was his word against the other man’s. So he was just lucky. That was one of the other reasons he survived. It was because of his wit.

During that time in 1941, shoes made a difference between life and death.

We don’t know if the other guy survived. My grandpa never used the word stole. That was my word. He never said he stole the shoe because that pair of shoes didn’t belong to anyone. It was something he found, but he kind of used his quick thinking to get the second shoe. Yelena [Lembersky] wanted me to take that story out of the book because she said it doesn’t show my grandpa in the best light. But I left it in because I feel that every person has good points and bad points, and that’s what he had to do to survive.

Blumberg-Kason: I love how you said that people are not all good or all bad, that people are layered. There’s another part of your book that also I didn’t know about before. It was when you had just come back from Ukraine for your book research, and then you found out that a synagogue in Moldova was vandalized, which was shocking to the Jewish community. But not too long after, that town elected a Jewish mayor who was born in Israel. When I read that, I also thought about how you said you feel very uncomfortable being outwardly Jewish in Ukraine because of the anti-Semitism there. But there’s also the fact that Ukraine elected Zelensky as their president. So it’s kind of like Moldova has anti-Semitism and that town elected a Jewish mayor, and then Ukraine has anti-Semitism, but they elected Zelensky. Can you speak more about this contrast?

Masis: I remember I was writing a story for the Times of Israel when Zelensky was first elected. I tried to reach out to his office to see if he would give an interview to the Times. At that time nobody in his office would confirm to me that he was Jewish. He refused to comment on it, and they didn’t want to say anything about him being Jewish. He was a very famous actor in Ukraine. There are situations where if a person is very famous, people will still elect them even though they’re Jewish. But a lot of times when I was traveling in Ukraine, I felt that as soon as I told somebody that I was Jewish, all of a sudden people would just see me as a Jewish person, and I didn’t always want to be seen as any kind of category because you don’t know when some people might not like Jews. I just didn’t feel comfortable with it. And just because they elected a Jewish president, I don’t think it means that they don’t have a problem with anti-Semitism. We elected Barack Obama here, and we still have racism.

Blumberg-Kason: Yes, that’s a really good point. I wanted to talk about your dad because he also grew up in the same town as your grandfather. Before World War II, this Moldovan town had a population of 3,000 people, of which 2,500 were Jewish.

Masis: It was like a shtetl.

Blumberg-Kason: Yes, and now all that’s left of the Jewish community is a cemetery. When your father was young, other kids would taunt him for being Jewish and would tell him to go back to Israel. He was really confused because Moldova was his home and he hadn’t been to Israel. Moldova was all he knew. How did he end up leaving Moldova? You were born in St. Petersburg, so he must have gotten to St. Petersburg at some point.

Masis: He went to university in St. Petersburg, and I think he considered that it was easier for a Jewish person to get into a university in St. Petersburg or Moscow than in Moldova, for some reason. There were quotas for Jews, and it might have been that Moldova had a higher population of Jews, so it was harder.

Blumberg-Kason: I want to turn to the structure of your book and the paintings you include with every chapter, all from Felix Lembersky, who is also featured in his granddaughter, Yelena Lembersky’s, memoir. How did you decide to use his artwork, and had you always envisioned an illustrated book when you started thinking about writing your family story?

Masis: I want to show you this book I’ve had since I was little. It’s called When Daddy Was a Little Boy, a Russian book by a Soviet Jewish author named Alexander Raskin. This book was an inspiration for my book because every chapter is short and has a little illustration. I think my book is similar because my chapters are very short and their memories of the past are like a story told by a family elder. And because my chapters are so short, I wanted to have illustrations. It was like it came from my subconscious because after I wrote my book, I thought it reminded me of something. And then I realized that Raskin’s book probably influenced it.

Blumberg-Kason: Did Raskin’s book include his Judaism, too?

Masis: It was never mentioned, but I know he was Jewish. And the funny thing was that at one point a year ago, I decided to look up the author on Wikipedia because I was wondering about his life story. And on the day I looked him up, it was in February and the exact anniversary of his death. It was just random. Now it’s just past the anniversary of his death again, because he died on February 4, which was two days ago. That other time when I looked him up, it was the exact date, which was really random. So I thought maybe he’s trying to communicate to me from the other side that I should get my book published.

Blumberg-Kason: I want to leave the topic of the book for a bit. I’m really interested in your work in Cambodia because I spent a couple of weeks there in 1991. But you lived and taught there and gave tours to the Khmer Rouge tribunal. What sparked your interest in Cambodia? And do you think you were drawn to another war-torn area because of your family history during World War II and even your own early years in the Soviet Union, when people could be taken away without warning?

Masis: I would say no. I am a journalist, and I just wanted to work abroad because I thought it would be interesting. So, I started sending my résumé to different English-language newspapers around the world. I had a desire to explore and travel and to have more adventure in my life. I started with the Caribbean because I wanted to go to the tropics, but that didn’t work out. And then I tried every newspaper in South America and didn’t get anything there.

Next, I thought I would try Asia. I tried India, but their websites were down, so a lot of the email addresses didn’t work. And then I found a newspaper that was called the Cambodia Daily. By the way, the Cambodia Daily was founded by a Jewish guy, I think a Holocaust survivor from Germany. The newspaper no longer exists, but at that time it was a daily English newspaper and I got a job offer. I didn’t even know how to pronounce the capital of Cambodia, so I had no idea what I was getting into. But they provided free housing in a villa, so I said okay. I spent about five years there and miss it. Maybe I’ll move back someday. I had a Cambodian boyfriend, which was probably the longest relationship of my life. It was from the age twenty-nine to thirty-four, so from 2011 to 2016.

I also taught English, and a lot of my students were Buddhist monks. And I did the Khmer Rouge tribunal tour. Because the Khmer Rouge tribunal was an hour’s drive outside the city and most tourists wouldn’t know how to get there, I offered these tours and hired a tuk tuk driver and did a little introductory talk. I wouldn’t say that I went to Cambodia because of my interest in genocide, but I think when I did learn about the Khmer Rouge period, it probably hit a nerve.

I wouldn’t say that I went to Cambodia because of my interest in genocide, but I think when I did learn about the Khmer Rouge period, it probably hit a nerve.

I grew up with stories about the Holocaust, and when I would bring these groups to the Khmer Rouge tribunal there would be survivors testifying about what happened to them. It was very powerful. I have been to Auschwitz for the March of the Living, and compared to the genocide sites that I’ve seen in Cambodia, I was just completely shocked by the scale of Auschwitz and the way everything was built and designed specifically with the intention of murdering the greatest number of people. It was on a huge scale, and it was all very well designed, very well organized, versus in Cambodia where it all just felt very random. It wasn’t like those schools were built specifically to murder people or that scientists were coming up with a plan of how they could kill the most people in the shortest amount of time. Not to say that one is better than the other or worse than the other, but I was just shocked by the scale of Auschwitz when I saw it.

Blumberg-Kason: Can you talk a little more about what you’re writing next? You mentioned earlier that you’re writing a book about your other grandfather.

Masis: My other grandpa, now ninety-six or ninety-seven, lives in Boston. He is the only one in my family who is actually from Russia. He was in the Siege of Leningrad, and his father starved to death in the siege, which you probably know about. A million civilians died from starvation. But the book is more about my grandpa’s work in Soviet aviation for fifty years, which is very rare. He had a very long career. Originally he was in the air force, and then he worked for Aeroflot, the civilian passenger airline. He was involved in investigating all the air traffic accidents where there were no human casualties. He told me a lot of interesting, funny stories. There’s a true story about how he fell from the airplane. The airplane was parked on the ground and he was on the wing servicing the plane. It was a cold day, and I guess the wing was iced over, so he slipped and fell from the wing onto the ground. It was pretty high up, so he became paralyzed on one side of his body for a while. My grandpa was stationed in the Far East, very close to Japan. He was on the very edge of Russia, close to the Pacific, and grandma was in Moscow. He wrote letters to her, and after his accident he couldn’t write because his right hand had become impossible for him to use. That was a story he told. There are other stories having to do with airplanes, and at that time the Soviet Union was the first to send a man into space.

And in terms of aircraft, in the 1950s they were also at the forefront. At some point they had the only jet engine passenger plane in the world, or the first one. It actually had a really terrible safety record because it was the first model. So my grandparents have a story about how they almost died when my they flew back to the Far East with my mom when she was a baby. For my book about my grandpa’s shoe, I wrote it about ten years ago and self-published it for my grandpa’s one hundredth birthday. Now the Academic Studies Press is republishing this book. It got good reviews and people liked it. It’s an old project, but the one about my other grandpa is something more interesting to me now, and that’s what I’m finishing up.

Blumberg-Kason: I am looking forward to reading it! Thank you for chatting with me about your fascinating books!