Responding to Nezahualcóyotl: A Conversation with Ilan Stavans

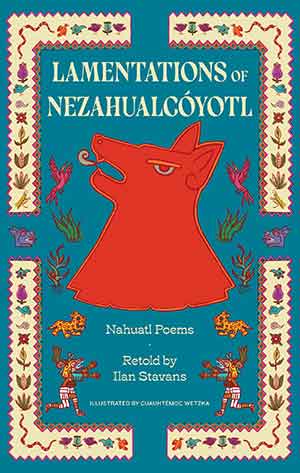

Lamentations of Nezahualcóyotl: Nahuatl Poems (Restless Books, 2025), by Ilan Stavans, is a collection of poems that capture, from original Nahuatl songs, the voice of Aztec warrior, king, poet, and philosopher Nezahualcóyotl, who lived half a century before the arrival of the Spanish. The following is a conversation with Stavans about the inspiration for his work, the texts he consulted, and his influences as he sought to find new ways for audiences to connect with Nezahualcóyotl.

Susan Smith Nash: I really liked the fact that, as you pointed out that over time, Nezahualcóyotl has achieved almost mythical status (at the very least, legendary) as a warrior-poet, philosopher, and, above all, king who foretold the coming arrival of the Europeans and the great suffering to come. As a kind of apocalyptic prophet, how much did the apocalyptic narrative shape your understanding of him? If you deliberately strip out the apocalyptic narrative, how does your perception of his work and his ideas change?

Ilan Stavans: Nezahualcóyotl, in my view, was a kind of prophet. One of the distinctions of prophesy is its apocalyptic nature. He died fifty years before the arrival of the Spaniards, yet in my eyes he foresaw the cataclysm that awaited his people. Of course, my Nezahualcóyotl is as much a creation as is the one of previous generations. Therein, I believe, lies the nature of historical figures: it isn’t so much who they were but who we want them to be.

Ilan Stavans: Nezahualcóyotl, in my view, was a kind of prophet. One of the distinctions of prophesy is its apocalyptic nature. He died fifty years before the arrival of the Spaniards, yet in my eyes he foresaw the cataclysm that awaited his people. Of course, my Nezahualcóyotl is as much a creation as is the one of previous generations. Therein, I believe, lies the nature of historical figures: it isn’t so much who they were but who we want them to be.

Nash: His themes, concepts, and historical references take the reader to another world, and I appreciate the readerly journey. Where did you find the source documents? Are they in codices? Were they translated into Spanish? Much is mentioned in your foreword. Was it hard to find the originals?

Stavans: Growing up in Mexico in the 1970s, Nezahualcóyotl was an icon with a profound influence. A semi-autonomous “subcity,” adjacent to Mexico City, popularly known as Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl (abbreviated as Neza), becoming an independent municipality in 1963, was named after him. With an estimated population of over one million today, Neza sits over what once was Lake Texcoco, one of the five connected lakes over which Tenochtitlán, the capital of the Aztec Empire, was built. Neza used to be a slum, but it is now an astonishing place where one witnesses the capacity of Mexicans for self-reliance.

I remember learning in school that Nezahualcóyotl was a forward-looking leader as well as a poet, a philosopher, a warrior, and an urban planner. But much of the work about the Mexica past is conveyed to us by Franciscan priests like Fray Bernardino de Sahagún and Alonso de Molina, in places like Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco and other Spanish-language centers of learning during colonial times. The poems of Nezahualcóyotl are compiled in almost a hundred Nahuatl songs known as Cantares Mexicanos. I first read it in the Spanish translations by Ángel María Garibay and subsequently accessed the Nahuatl versions.

It is important to be cautious about the poems for a couple of reasons: first, like the biblical King Solomon, for instance, the poetry attributed to him was likely written by scribes within his court in Texcoco but attributed to him; and second, the transcriptions in Nahuatl and Spanish were produced in the sixteenth century, long after Nezahualcóyotl died in 1472. In other words, what we have are echoes of the poet.

What we have are echoes of the poet.

Nash: Are all the poems written in Nahuatl, and did the poems appear as they do in the collection, or did you take blocks and chunks and create the “retelling”? What was the process, and how did you make the decisions that you made?

Stavans: In 1985 John Bierhorst, who once edited an anthology of Latin American folktales, did a scholarly translation of Cantares Mexicanos. He called it Songs of the Aztecs. It wasn’t a poetic translation but an archaeological one. Reading him and Garibay, and exploring the códices where Nezahualcóyotl makes an appearance, I felt he was calling me, asking to be brought back to life, rescuing the figure of my childhood that has gained in size and influence as I have grown older. In order to accomplish that, I set myself the task of learning as much as I could about Nezahualcóyotl’s time: his language, his culture, his legacy.

Nash: There are many poems that describe the action of self-reification, and the conditions that lead up to the need to reinvent oneself. What are some of the different ways, and precipitating factors, that make Nezahualcóyotl shape the notion of self-creation?

Stavans: He isn’t an innocent leader—no leader ever is. In fact, he is not only narcissistic but transactional: since he knows he will be remembered, he wants to manipulate that legacy to the best of his ability. Still, fame is always a betrayal.

Nash: There are many references to the power of language—they seem almost Wittgensteinian at times (“the limits of language are the limits of my world”), and at the same time, there is a current of animism and shape-shifting. I’m reminded of the Mayan poets who use language as invocations, to animate inanimate objects. This could contribute to the atmosphere of “lo real maravilloso,” but even more powerfully, it seems to reflect back to Indigenous Mexican beliefs and how they are built into the language so that prayers and invocations result in casting spells to harness the spirits in everything around one to help with life. What are your thoughts about that? How did you meld Indigenous ways of viewing language with your translation?

Nahuatl must have been like Sumerian at the time of Gilgamesh, Latin in the Middle Ages, French during the Enlightenment, and English in our age of besieged globalism.

Stavans: I am weary of the way the Indigenous past is romanticized. The Mexicas—the term “Aztec” wasn’t used by them—were as manipulative and self-interested as we are today. What intrigues me, though, is their language. How did they use it? Or better, how did they abuse it? Nahuatl was the lingua franca in Tenochtitlán, a neutral tongue that allowed merchants, warriors, priests, slaves, and others from a variety of backgrounds to interact with each other. Scholars believe that when Hernán Cortés conquered the city, there were sixty-eight languages spoken in the region. Nahuatl must have been like Sumerian at the time of Gilgamesh, Latin in the Middle Ages, French during the Enlightenment, and English in our age of besieged globalism.

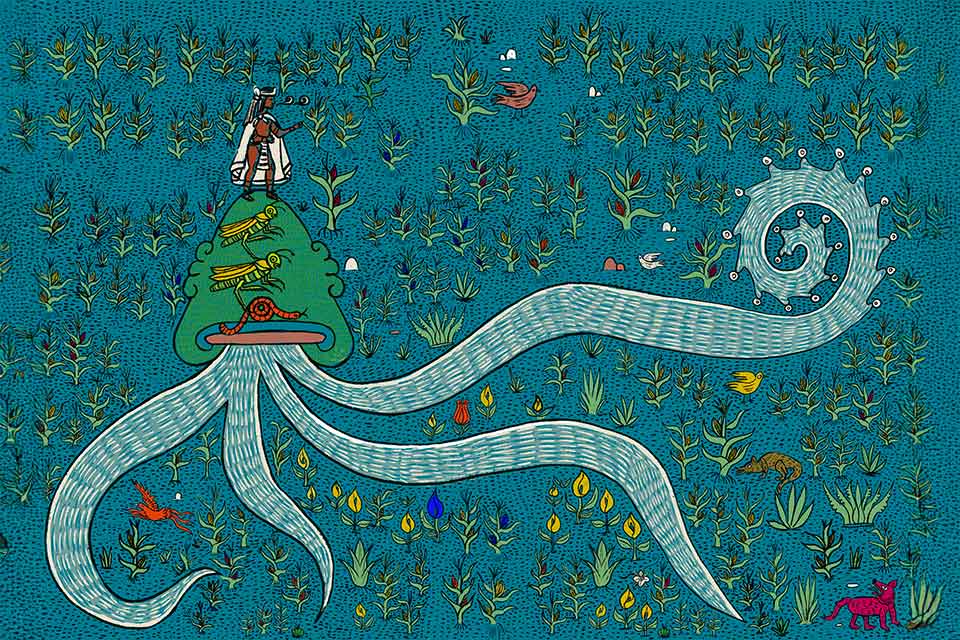

As for magical realism, to me Nezahualcóyotl’s voice is a forerunner to Jorge Luis Borges, Alejo Carpentier, and Gabriel García Márquez. His imagery intertwines the real with the dreamlike, though not in a cutesy way. He interrogates what is authentic and what is imagined, often concluding that the thin line separating the two is itself fictional. He is like Cortázar’s axolotl. Yet I also recognize in him countless other echoes. In short, Nezahualcóyotl for me is a universal poet whose work paves the way—anachronistically—to Rumi, Shakespeare, Quevedo, John Keats, Cavafy, Pablo Neruda, and Seamus Heaney. Why not? In poetry, none of us is imprisoned in the present.

Nash: There are several passages that refer to punishment—and punishment for different offenses and types of people. In many ways, it is a way of identifying the “Other”—but for what? For example, is it for punishment? Or, for opening the door to at least admitting the ideas of the Other?

Stavans: There is no civilization that isn’t complex. The Mexica world, like ours, was obsessed with rules: how to placate the ire of the gods, who should live and who should die, what is a worthy life, the chaos of nature, and so on. There was a strict legal code that condemned alcoholism, pederasty, and other deviations from the norm. In their catechism, the Spaniards called this behavior sinful. The Mexican didn’t believe in sin, which doesn’t mean they didn’t have a concept for abhorrence.

Nash: There are so many different concepts—so profound! I have made a list of at least a dozen, and I’d love to explore them. Some include the ambiguous nature of reality, the ephemeral nature of our own lives, the foolish quest to own the earth (which belongs to no one), the way we set ourselves up to be conquered by first vanquishing ourselves through self-destructive behavior . . . and these are just a few.

Stavans: The Spanish believed the Mexica to be barbaric, just as the Mexica saw their unexpected visitors from the sea as barbaric. It was a colossal clash of cultures. The Spanish killed millions, yet today they carry the burden of those atrocities. In truth, there are no winners and losers in history. Things always appear to happen just now, yes, right now. But the present is a mirror: malleable, evanescent, and fragile. There are countless ways to interpret it.

The present is a mirror: malleable, evanescent, and fragile. There are countless ways to interpret it.

Nash: After working with so many texts and immersing yourself in time-travel (rather than “history,” because what you have done has the intensity of an immersion), and a union with the texts and the idea of the person, what are the top four or five concepts that consistently rise to the top?

Stavans: I am an immigrant from Mexico to the United States. And I am from a family that came from Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine to Mexico. My life has been about motion. Yet it’s the roots of my childhood that ground me. I sometimes see Nezahualcóyotl appearing before me at night: vigorous, emblematic, resonant in his silence. We are all what others make of us. Through this immersion, I have used the languages that were granted to me, the languages at my disposal, to pay the enormous debt I owe to Mexico.

Ilan Stavans is the Lewis-Sebring Professor of Humanities, Latin American, and Latino Culture at Amherst College, the publisher of Restless Books, the co-founder of the Great Books Summer Program, and a consultant to the Oxford English Dictionary. His award-winning books include, most recently, Sabor Judío: The Jewish Mexican Cookbook (2024, co-written with Margaret E. Boyle) and, due out soon, Lamentations of Nezahualcoyotl, Jorge Luis Borges: A Very Short Introduction, and the children’s book The Secret Recipe. His work, adapted into film, theater, TV, and radio, has been translated into twenty languages.