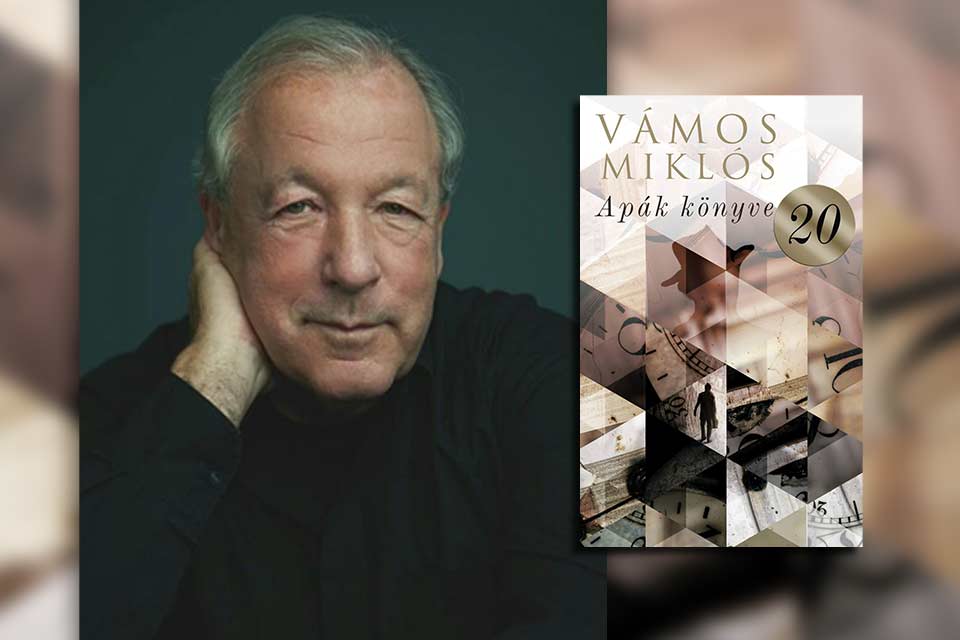

Jubilee Musings on The Book of Fathers

This year marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of Hungarian author Miklós Vámos’s most successful work, Apák könyve (2000; The Book of Fathers, 2006). In this essay from the twentieth-anniversary edition of the novel, Vámos touches upon the craft of writing and the laborious research that goes into bringing a tome like The Book of Fathers to completion. He also shares anecdotes that give us a glimpse into his life, including lunch with Péter Esterházy at an Australian restaurant.

Once upon a time there was an author who, many moons ago, published a widely acclaimed novel, The Book of Fathers. One night, after a particularly hard day, he finds himself in a dream where he is celebrated worldwide for having turned a hundred years old. At this phantasmagoric global soirée, he is the only one unaware of his advanced age, and, with a series of ad-libbed moments, he startles his fans by insisting that he is only fifty. After more awkward twists and turns he awakens, his pillow drenched in saliva, his forehead beaded with sweat. He sifts through his thoughts, the fog lifts from his brain, and when he is finally wide awake he reminds himself that he was fifty when his novel came out, and now he is in his seventies. Surely not a hundred yet, though he is slowly inching his way toward becoming a centenarian. Hence, The Book of Fathers is a quarter of a century old, which, he concludes, is something else.

Now, from dreamland to reality. My readership knows that I wrote a book about my mother in the early 1990s, so it seemed only fair that I would dedicate one to my father as well. My father spent more time in World War II than what was the duration of the war. He graduated from university prior to the war breaking out, and soon after he was enlisted as a private and forced to partake in various movements, which included invading neighboring territories that belonged to Hungary before the Treaty of Trianon. Because of anti-Semitic laws, my father was transferred during the war from a regular army unit to a labor service battalion. Along with other unfortunate souls, he was stripped of his weaponry and was routinely sent ahead, straight onto the minefields, to “clear the road” for their army unit. By a fortunate twist of fate, he was one of a handful of survivors. After the war, the Russians captured him and detained him as a prisoner of war along with others from Germany, Italy, Hungary, and elsewhere—there was no investigation or a trial. He escaped from that hellhole and walked his way to freedom. The arduous walk lasted for months. When he arrived in his hometown of Pécs, he learned about the fate of his relatives—his entire family had been murdered in the Holocaust.

I was in my late teens when I found out about these horrific events. Furthermore, it came to light that I was a Jew, which was a complete shock to me. In elementary school I unwarily cursed and called out names with my classmates left and right, thinking that the word “Jew” was just another swear word. Stupid! Idiot! Schmo! Jew! My first high school girlfriend had asked me if I were a Jew. Who, me? Don’t be silly! How could I possibly be a Jew? But when evening rolled around, I mentioned to my father that she thought I was a Jew. He pushed his reading glasses up and rested them on his forehead: My dear son, there is some truth to that. I stared at him aghast, unable to speak. He summed up everything he wished to say about this topic in two short sentences. He never uttered another word about it for the rest of his life.

Don’t be silly! How could I possibly be a Jew?

“Jews” or “Judaism” were not words that passed anyone’s lips in my family throughout my childhood. In socialist Hungary there were no Jews or Gypsies or Swabians or, for that matter, Hungarians. What we had were proletarians of the world who needed to unite. My classmates were not better informed either. Decades later, I still don’t know a word of Hebrew or Yiddish, and I am clueless about Jewish prayers, kosher foods, culinary or other traditions. Regardless, when Jews are on the chopping board, I feel the need to stand up for my people—given my family history, that’s the least I can do for my ancestors whose past had been so star-crossed. If you ever forget that you’re a Jew, a Gentile will remind you—wise words from the Talmud.

I am humbled that The Book of Fathers is considered my masterwork both at home and abroad. It’s been said that it is one of the most prominent works of Hungarian prose in the twentieth century. Kate Saunders wrote in The Times that it is “a superb family saga that draws the reader effortlessly through nearly three centuries of turbulent history. . . . It records the political upheavals of an entire nation. The characters are fascinating and Vámos’s writing is a magnificent, seamless blend of the general and the personal.” This warmed my heart to no small extent. I cracked open a bottle of champagne to celebrate with my then-best friend. Additional encomia followed, one of them from the American writer Tama Janowitz: “Reading this you feel as if Márquez had a lost younger brother long exiled in silence to Eastern Europe. We are so lucky to have this talented author—and The Book of Fathers—translated into English at last.”

I can’t help but wonder how the book engages and influences its readers nowadays, twenty-five years after its publication. Books written back then and translated into Hungarian sometimes can seem slightly outdated by now, especially if their narratives contain a lot of slang, the part of prose most prone to deteriorating. Fortunately, this is not a subject of contention in The Book of Fathers, whose narrative is written so that with each ensuing chapter the language changes gradually, seamlessly morphing from old-fashioned into modern-day Hungarian, not vitiated by colloquialism and slang. It is my sincere hope that my work will stand the test of time.

It seems like only yesterday that I spent untold hours, day after day, gathering materials in the Library of the Hungarian Parliament. To my dismay, my laborious undertaking took place roughly thirty years ago. The Library of the Hungarian Parliament at one time used to be a favorite stomping ground for me and my fellow students of law. The preparation to write my book required an immense amount of research, so I was chained to library desks for seven years straight, both figuratively and literally. Back then the internet was an unknown marvel of technology, and therefore important quotes had to be copied by hand or photocopied. My collection of binders grew thicker with each ensuing week. For a change of scenery, sometimes I visited the cozy library at the Society of Hungarian Authors, or the grandiose National Széchényi Library located in Buda Castle. After seven years, it took me another three years to organize everything and write the actual manuscript by hand.

The preparation to write my book required an immense amount of research, so I was chained to library desks for seven years straight, both figuratively and literally.

Having meandered across the novel’s ever-changing landscape for a decade with my pen in hand, I was ready for its publication. What better time, I thought, than during the Budapest Book Week, in the highly anticipated year of 2000. Coincidentally, that was the year I turned fifty, so my timing seemed fortuitous. The year prior I was invited to several book fairs abroad. I flew back and forth, making use of the now-defunct Hungarian airline MALÉV. One of the airline magazines featured an interview with Péter Esterházy. He was asked about his upcoming book, also due to be out during Budapest Book Week. His novel, he explained, was about his family’s eight-hundred-year-long history, with a focus on his parents. Centrifugal forces arose inside of me and almost made me choke on my bland airplane sandwich. I suddenly feared that he might have also come up with the same idea of archaizing the language of his narrative. This was a very real possibility, since his book covered an extensive time period, too, and he has always been such a juggler of words, a shining literary star. I spent endless nights mulling over the complications this might cause regarding the timing of my book.

Centrifugal forces arose inside of me and almost made me choke on my bland airplane sandwich.

My patience was wearing thin, so upon my return to Budapest, I called him immediately and proposed a lunch meeting at an Australian restaurant, of all places. We met a few days later. By dessert, I was anxious to find out from him about his project. He said it was practically completed, and he was happy to share details. The more he shared, the less anxious I became. Before long, my reservations vanished—he mentioned nothing about language. In between taking small sips of his coffee, he inquired about my forthcoming book. I summed it up in about ten sentences, briefly hinting at my stylistic idea. He looked at me through his glasses, his glare ever so piercing: But that is extremely risky! He was, of course, referring to the archaizing of the language. I switched topics, not wanting him to deter me from my idea, especially because mine, too, was practically completed. If I may humbly say so, it became a raging success in Hungary, and when it crossed the borders, readers lapped it up abroad, too. To say that I was overjoyed would have been an understatement—I felt like I was on top of the world.

The next time Péter and I talked was at the Frankfurt Book Festival, in the middle of a cacophonous pavilion. He had no memory of alluding to the dangers that might have lain in my playing with the language. It no longer mattered, yet it felt reassuring to know that his comment didn’t play as important a role as I thought it did—he didn’t even recall saying it.

It was back at the Australian restaurant that an idea came to me: if Péter planned to publish his Harmonia Celestis during the Budapest Book Week, I would let him go ahead, then publish The Book of Fathers later in the year. It would be best not to take the spotlight away from each other. Four months later mine came out. A deluge of interviews followed, and despite my novel weighing in at nearly five hundred pages, it never stopped any reporter from asking: Now that Esterházy wrote a book about his father, why did you suddenly decide to write one, too? Perhaps I shouldn’t have postponed my publication, I thought. There is a price to pay for generosity.

How anyone could assume that this monumental task could have been accomplished in four months was incomprehensible to me. Furthermore, on the last page were printed the years it took to write it. This used to annoy me back then, but by now it’s all water under the bridge, and it warms my heart to be associated with him in this or any other respect. I wholeheartedly recommend Harmonia Celestis to everyone, and if they find the first part too demanding, they could start with the second one. Esterházy would surely forgive them for it.

This labor-intensive book has an ethos and fundamental message.

But to whom would I recommend The Book of Fathers? Sometimes I feel like everyone has read it already. But there are always the younger generations. How will they like it, and what feelings will arise in them? Heaven only knows. One thing is certain: this labor-intensive book has an ethos and fundamental message. Literature in the twentieth century began to heavily focus on how difficult life was (true). In the twenty-first century, it went further: life is unbearable (true). At the forefront of my narrative, the embedded message is unmistakable: despite worries, problems, and tragedies, life is also wonderful, and we must remain hopeful. If readers believe that, then perhaps everything will be a little better. Let us hope so.

Translation from the Hungarian