The Colors of Poetry: Anna Frajlich’s Lifework

Alice-Catherine Carls offers a career-spanning overview of the work of Polish writer Anna Frajlich.

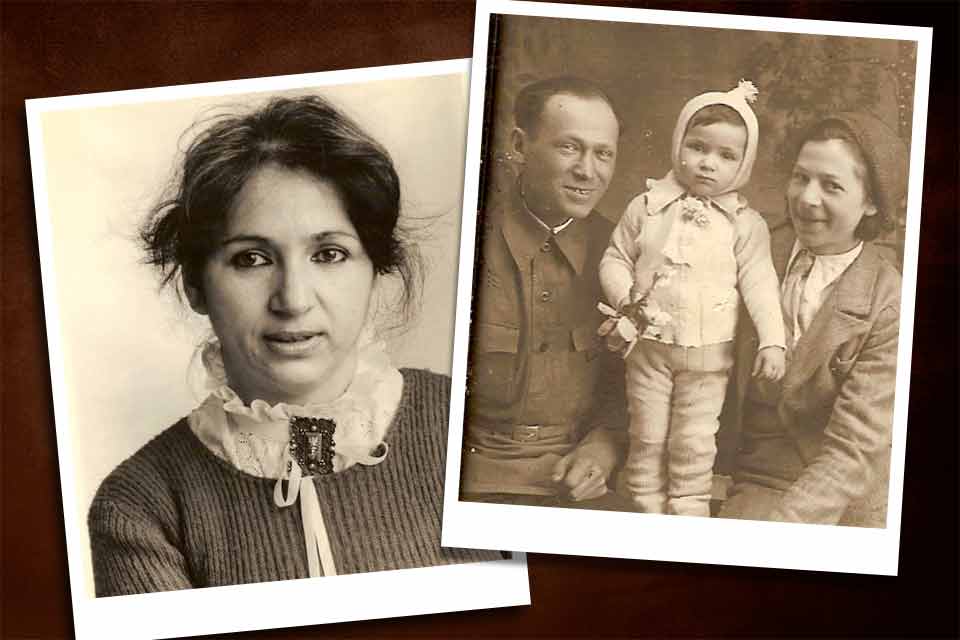

A few weeks after having been expelled from Poland on November 12, 1969, Anna Frajlich (b. 1942, Kyrgyzstan) arrived in Rome with her husband and two-year-old son. Facing her first Christmas in exile, living off care packages her parents had sent her, she wrote daily letters. On December 1, 1969, she wrote to her parents:

Most of all, I love to be in the kitchen. Cooking is best suited to satisfy my ambition. I buy various greens and herbs that we have not yet tasted, and I season everything with olive oil. Every night I make almost elaborate sandwiches, and I build salads that have at least five colors.[i]

A few months after settling in New York, while commuting by train from Brooklyn to Stony Brook for her first teaching assignment, she wrote to her parents on October 14, 1970:

The fall season is very warm here and exceptionally beautiful. I can appreciate this particularly during my travels. Today I couldn’t read; I could hardly take my eyes off the colors. Flowers still have their summer blooms, and the tree leaves take on fantastic colors, from celadon and yellow through all shades of red to crimson. And, strangely, for even in Italy it does not happen, the leaves do not fall. The trees look as if they had suddenly bloomed into huge, colorful flowers. It is truly beautiful.[ii]

Nature’s colors are all-important in Frajlich’s poetry, as seen in her first poems in Fołks-Sztyme. After she emigrated, nature provided her with a way to unite the life she had just lost with her new life. Colors represented both contrast and continuity in her life and her poetry. Contrast, because in Poland, fall colors range from yellow to brown, while in the United States they are brilliant and dazzling. Continuity, because the colors of food are the sustenance of life; artfully assembled in salads, they are both healthy and aesthetically pleasing. Nature’s permanence and memory were thus vital during Frajlich’s adjustment to the new world.

These two excerpts show Frajlich’s refusal to have her life cut in half and her determination to counterbalance the pain of expulsion from Poland, without hiding it, yet without letting it win. Her correspondence during the first two years of her life in exile shows that at the deepest levels of her being, the dynamics of her life in Poland—readings, food, and family—were unbroken, especially her close ties to her parents and close family. Her early reaction to pain illuminates her entire work and explains better than any theory how her most intimate feelings remained unbroken, allowing time to flow uninterrupted.

Frajlich’s limpid language contains a wealth of images with related metaphors and allegories.

Nature is an important theme in Frajlich’s poetry. It recurs in her poems about pearls, an organic creation that represents resilience and possesses an iridescent, translucent glow. Likewise, Frajlich’s limpid language contains a wealth of images with related metaphors and allegories. She uses French philosopher Henri Bergson’s description of events as isolated and unmemorable unless they are held together like pearls on a string, creating memory and meaning across time. If time is for Bergson a mechanical thought process, however, Frajlich considers it as the product of a fluid, organic buildup. Furthermore, a pearl starts with a grain of sand, an irritating wound that causes pain. In a striking comparison, Frajlich likens the pearl’s growth inside the oyster to the child growing in a mother’s womb, becoming a work of art and beauty in the fullness of time. In the poem “From Bergson,” we read:

Time is not a row of pearls

just one pearl

wrapped around

the seed of an unhealed wound

soaking a fluid mass

eternal and changing

and filling

the unnamed immensity

with its presence.[iii]

As noted by Jan Zieliński, Frajlich in this poem also refers to the Dutch master Joannes Vermeer’s painting Woman Holding a Balance.[iv] According to Zieliński, Frajlich sees the pearl as the woman’s unborn baby and the balance as a meditation on life and death. As for Frajlich herself, her “grain of sand” was the anti-Semitic campaign of 1967–69, during which her pregnancy was endangered, and which ended with her exile. Her personal pain resonates with the anguish of the persecution of Jewish communities before, during, and after the Shoah, and extends to the history of the Jewish communities of eastern and central Europe. It recedes somewhat, as we read in the poem “About Pearls”:

The pain that gave them their start

has stopped to hurt

why then do you subject

them to unceasing scrutiny

must they pay such a price

for their luster

or because

they hang coldly

around your neck?[v]

Dedicated to Renata Gorczyńska, this poem shows that the unfeeling cold of the pearls reminds us of the pain from which they were born and that their beauty, which represents victory over pain, can never let us forget it. Poetry likewise is born from pain and brokenness. A mirror, for example, reflects both time and color, can be broken, as we see in the poem “Hemorrhage”:

A fragile object linked

to the entire universe

is filled to overflow

dizzy with excess.

The mirror

that once crossed

wide spaces

lay broken by the roadside

and each of its fragments reflects

the fluffiness of maple buds

the immensity of the sky.

A bird’s wing shines

in a thousand fragments at once.

That which was united

is no longer united

that which was fragile and whole

has been crushed.[vi]

A broken mirror can no longer be useful in the ways for which it was intended. Its fragments must reinvent themselves even if, as the poem intimates, despair seems to prevail. A broken mirror’s ability to reverberate the world in a thousand pieces can create beauty despite the apocalypse of violence and pain to which it has been subjected. In the same way, a glass ceiling can and should be broken to make way for new creation. In the eponymous poem, we see birds often hit a patio’s glass ceiling. The poet then observes:

I, too, stubbornly hit

the glass ceiling of language

thus I planted a red flower

to attract hummingbirds

one morning they will hear

the promise of slender calyxes

unspeakably sweet

in purple splendor . . . [vii]

Frajlich’s awareness in building a delicate balance between pain and joy in her life is perhaps the most important lesson we can learn from her poetry. Her life is a long kaddish that respects, remembers, and empathizes with the past and yet firmly affirms life. The main themes of her poetry represent an act of defiance against the violence to which she and her family were subjected. They deal with what is most important in human encounters: friendship, love, empathy, community, memory, and time. It takes courage to break such a glass ceiling. Just as her life is quietly revolutionary in its affirmative choices, her work speaks directly from the heart to that which is most human in us and does it with a light footprint’s poignant beauty.

Frajlich’s life is a long kaddish that respects, remembers, and empathizes with the past and yet firmly affirms life.

This is why Sławomir Żurek’s Szklany sufit języka. Trzynaście rozmów (The glass ceiling of language: Thirteen conversations) is so important. The thirteen conversations let us hear Frajlich’s voice “live” and complement her discussion of a topic with poems and excerpts from numerous essays and diaries that are not readily available to the reader. In these conversations, she becomes a witness, giving indispensable first-person testimony about her life and work. Through thorough research, Żurek has intuited the well-rounded, wholesome nature of her creation, and his questions do not try to separate life experiences from poetic creation. Rather, they prompt Frajlich to delve deeper in her memory and to give greater detail. The result is a full genealogy of her poetry that is structured in two parts: “Dead Addresses with a Manhattan Background” and “The Price of Banishment.” In the first part, Żurek examines each of the seven places where Frajlich and her family lived: Lviv, Katta-Kaldyk, Szczecin, Warsaw, Vienna, Rome, and New York. In the second part, he examines her major activities: her first trips to Israel and to Poland after the end of the Cold War, her interactions with writers as a literary critic, the important people she met in exile, her view of poetry and poets, the fate of the émigré writer, and time/duration.

Regarding the well-rounded nature of Frajlich’s outlook on life, Żurek stresses the cosmopolitan community of her younger years. She grew up hearing and speaking Polish, Russian, Yiddish, German, and Hebrew. While in exile, she learned Italian and mastered English, and she modeled the community that her family was able to rebuild after World War II; she looked for surviving relatives, obtained genealogical and legal documents, established contact with Polish and Ukrainian émigré writers around the world, and created a unique diasporic literary community. As her thirty-two-year correspondence with Stefania Kossowska, the editor of the London-based Wiadomości, shows, Frajlich seamlessly wove life and writing, becoming a poet and prose writer, a journalist and essayist, a columnist and literary, film, and theater critic, a graduate of Polish studies, a literary scholar, and an academic.

How does one study a life that features so many aspects, stages, themes, and accomplishments? Is it possible to avoid repetition or to not miss something? Writers of traditional biographies will no doubt struggle to structure their approach. Anna Fiedeń-Kulak’s just-released excellent biography, Emigracja, tożsamość, pamięć. Życie i twórczość literacka Anny Frajlich (Emigration, identity, memory: The life and literary work of Anna Frajlich) provides an example of these difficulties. Fiedeń-Kulak deals with place in the first two chapters, distinguishing between the places where Frajlich lived and the representation of these places in her poetry. Using the poet’s essays and diaries, she deals with what she calls Frajlich’s “trifold” identity (Jewish, Polish, American), then delves into three themes (i.e., three forms of knowledge): of the world (memory, biology, and dreams); of man’s relation to the world and culture; and of nature (flowers, landscapes, nature vs. culture). Fiedeń-Kulak’s work, primarily academic, is heavily predicated on literary theories that are useful to situate it in the present state of scholarly research. While she deals with the same themes as Żurek, she portrays a completely different person.

Frajlich has created a life’s opus in the shape of a pearl.

With a literary career spanning more than sixty years, Frajlich has created a life’s opus in the shape of a pearl. Day by day observing, listening, expressing, processing, and nurturing the world around her, she has written about it with a footprint so light as to seem invisible. No matter what life threw at her, she overcame it, discreetly, patiently. One letter at a time, one poem at a time, one article at a time, she made a difference in countless numbers of lives, informing, educating, giving hope, providing support. Her parents’ legacy was their experience of several wartime exiles and postwar displacements. Her life mirrored theirs, from postwar displacement to her expulsion from Poland at the height of the anti-Zionist campaign of 1968–69. With her Polish passport and citizenship revoked, she, with her husband Władek and her son Paweł, were not unlike Mary and Joseph fleeing to Egypt.

Almost sixty years later, her publications have reached fullness. A few years ago, two volumes of her correspondence were published (2007, 2008). Jolanta Pasterska gave prominence to the diversity of her work in a collection of scholarly articles (2018), and Ronald Meyer edited a volume of her most important essays (2020). This year, besides the two biographies by Żurek and Fiedeń-Kulak, the third volume of her collected works has just appeared. It contains new and unpublished poems and rounds up a five-year project. If one counts the numerous journal publications, the sum of all her published work well exceeds three thousand pages.[viii] She is currently traveling through Poland for a series of twelve literary appearances, starting with an evening in Warsaw on October 5, and in Łódź, Poznań, Szczecin, Lublin, Rzeszów, and Kraków until October 29, giving her audiences a chart to navigate away from adversity into survivance.

University of Tennessee at Martin

Bibliography

Felicja Bromberg, Anna Frajlich, and Władysław Zając. Po marcu – Wiedeń, Rzym, Nowy York (Warszawa: Biblioteka Midrasza, 2008), 302 p.

Anna Fiedeń-Kulak. Emigracja, tożsamość, pamięć. Życie i twórczość literacka Anny Frajlich (Reszów: Bonus Liber, 2025. 495 p.

Anna Frajlich. The Ghost of Shakespeare: Collected Essays. Edited and with an afterword by Ronald Meyer (Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2020), 294 p.

Anna Frajlich. Wiersze zebrane. Tom 1: Przeszczep (Toronto, Szczecin, Bezrzecze: Wydawnictwo Forma, 2022), 207 p.

Anna Frajlich. Wiersze zebrane. Tom 2: Powroty (Toronto, Szczecin, Bezrzecze: Wydawnictwo Forma, 2022), 237 p.

Anna Frajlich. Wiersze zebrane. Tom 3: Pył (Toronto, Szczecin, Bezrzecze: Wydawnictwo Forma, 2025), 242 p.

Anna Frajlich & Sławomir Jacek Żurek. Szklany sufit języka. Trzynaście rozmów (Kraków, Budapeszt, Syrakuzy: Wydawnictwo Austeria, 2025), 404 p.

Jolanta Pasterska, ed. Studia i szkice o twórczości Anny Frajlich (Kraków: Księgarnia akademicka, 2018), 433 p.

Stefania Kossowska. Definicja szczęścia. Listy do Anny Frajlich, 1972–2003 (Toruń: Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika, 2007), 214 p.

[i] Felicja Bromberg, Anna Frajlich, and Władysław Zając, Po marcu – Wiedeń, Rzym, Nowy York, 25.

[ii] Bromberg, Frajlich, and Zając, Po marcu, 221.

[iii] Anna Frajlich, “From Bergson,” in Znów szuka mnie wiatr, 43. The poem is dated September 23, 2005.

[iv]Jan Zieliński, „Pojedyńcza perła,” Przegląd polski, August 25, 2008, 1, 11.

[v] Anna Frajlich, “About Pearls,” in W słońcu listopada, 40

[vi] Anna Frajlich, “Hemorrhage,” in W słońcu listopada, 30.

[vii] Anna Frajlich, “The Glass Ceiling,” in Łodzią jest i jest przystanią, 40.

[viii] This year alone, two journal publications appeared. Anna Frajlich’s essay “Przesuwać granice rozumienia” followed by poems was published in Migotania no. 3/88 (2025). Poems appeared in Akcent no. 3/181 (2025): 7–8.