Ways We Survive (or How Fiction Helps Us to Understand Violence)

Looking at the work of three writers—Han Kang, Mariana Enríquez, and Margaret Atwood—Catalina Infante Beovic finds stories that allow readers to freely exorcize the fears inherent to our times.

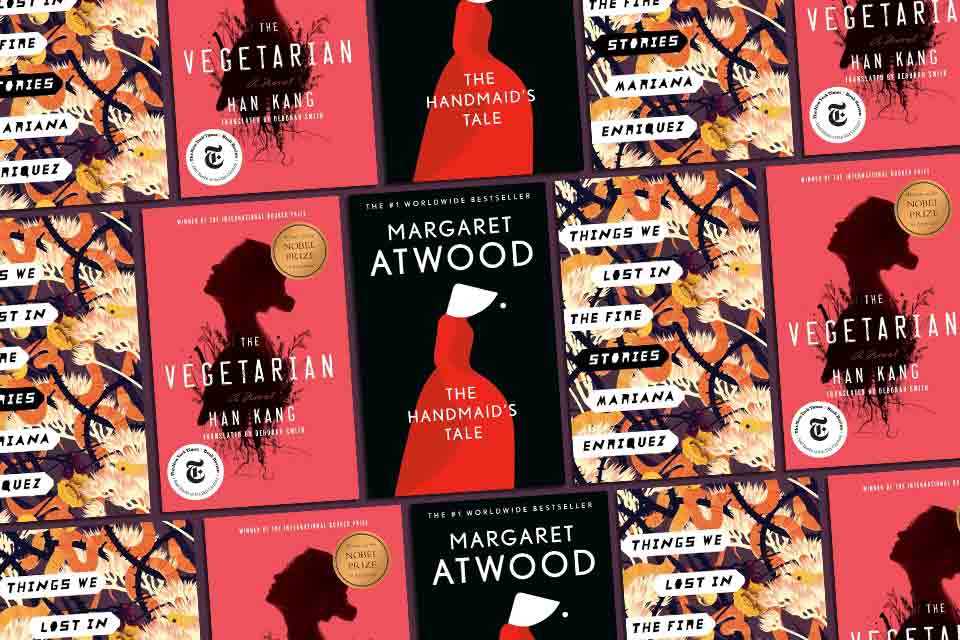

Yeong-hye wanders naked through a forest. She’s skeletal, doesn’t eat, hardly speaks, but she’s free. Free of her husband and her family, free of what’s expected of her, free of an entire culture’s violence and control. Yeong-hye’s body will all but disappear throughout the course of her resistance, but at least no one will be able to wield control over her. I’m talking about the protagonist of The Vegetarian, South Korean author and 2024 Nobel Laureate in Literature Han Kang’s most well-known novel (see WLT, July 2016, 91). (Translator’s note: The Vegetarian was translated into English by Deborah Smith, and La vegetariana was translated into Spanish by Sunme Yoon.)

The story is sufficiently outrageous with elements of the fantastic, despite not being classified as such: an everyday woman decides to stop eating meat and finds herself at the mercy of her family’s objections. In the wake of this simple decision, she’ll experience such violent backlash that she’ll wind up pushing her body to the extremes of anorexia, releasing herself from the human condition in pursuit of becoming a plant. The Vegetarian is now considered one of the greatest books of this century, a contemporary classic with sales success around the world. And I wonder—beyond the obvious interest a Nobel Prize drums up in the book industry—what special thing this story has done to connect with so many readers globally. The answer, I think, is in Han’s ability to narrate something as complex and yet commonplace as violence, approaching it as something intrinsic to human beings as opposed to some calamitous outside force, as something we experience and perpetrate daily and that, nonetheless, is so difficult for us to recognize in ourselves. That the victim of this violence is a woman, and the perpetrators those closest to her, I dare say, is what draws women readers in particular to this book; they’ve found in it a certain insight into the violence they themselves experience when they defy conventions. As with Yeong-hye, any woman making a personal choice that challenges what’s expected of her can unleash, depending on context, a sweeping range of violences from the most subtle to the brutal, just like in the book.

Han Kang is of course not the only author currently using elements of the fantastic to depict violence against women. Over here, an ocean away, the Argentine author Mariana Enríquez, in her story “Things We Lost in the Fire,” translated by Megan McDowell, tells of a group of women who decide to burn themselves in protest of their violent reality, a reality in which women are burned by their partners to punish and control them. We know, from the author herself, that this story was based on a real-life case: Wanda Taddei, an Argentine woman who was doused in alcohol and burned alive by her husband. The news, which sent shock waves through Latin America, drove Mariana Enríquez to pen a fictional tale where, extrapolating from an already extreme situation, women use their bodies to engage in an act of resistance: they burn themselves as a sign of liberation, so they are no longer objects of desire and so those men have no one left to burn. “Burnings are the work of men. They have always burned us. Now we are burning ourselves. But we’re not going to die; we’re going to flaunt our scars,” says one of the characters in the story. As in The Vegetarian, women use their bodies as a means for liberation, even when that resistance destroys them.

As in The Vegetarian, women use their bodies as a means for liberation, even when that resistance destroys them.

I’d hate to turn this essay into a list of already known facts, but it never hurts to reiterate a truth we forget far too often.

Around the world:

every ten minutes a woman or girl dies at the hands of her partner or another member of her family;

nearly half of all women do not control decision-making in regard to their own sexual and reproductive health;

one in every ten women lives in extreme poverty;

women experience greater food insecurity than men;

women have fewer chances to access financial institutions or a bank account;

women have fewer chances to participate in the labor market than men all over the world.

I could spend the rest of this essay adding to this list, but I don’t want to get too offtrack: coexisting with these facts, for any woman, is a violent experience. And literature, ever a reflection of reality, turns out to be a good way to channel that anguish. It’s no surprise that women storytellers of today are echoing this reality in their work across different genres. And perhaps it’s the genres with elements of the fantastic—psychological terror, science fiction, or “the uncanny”—that are offering the freedom needed to reflect this reality and rebel against it; meanwhile, these stories allow us as readers to freely exorcize the fears inherent to our times.

Another standout example of an author who, for decades now, has tackled gender violence through fiction is Margaret Atwood. Her dystopian/futuristic—and, as she’s spoken of, prescient—saga, The Handmaid’s Tale, is a clear critique of the oppression of women. In the novel, due to a global birth rate crisis, women are stripped of their rights and liberties, and more well-to-do families treat them as objects to be used in procreation. Blaming terrorism, the political and religious class seizes power in the United States, pouring their core values into a totalitarian regime that controls women and punishes dissidents. It’s curious that despite its 1985 publication date, this work is really having a moment, gaining popularity with its adaptation to television. The Handmaid’s Tale channels collective fears about the erosion of women’s rights due to the increase in traditionalist and even fascist discourse. What was already a fear in the 1980s seems today to take on even greater significance for its alarming proximity to reality.

The Handmaid’s Tale is a clear critique of the oppression of women.

Currently, and perhaps in response to more radical feminist discourse, the rights of women and girls are increasingly under threat throughout the world, from the highest levels of discrimination to weaker legal protections and decreases in funding for programs and institutions that protect women. In fact, in the United States—the very setting for Atwood’s novel—the constitutional right to abortion has been eliminated. “Nothing changes instantaneously: in a gradually heating bathtub you’d be boiled to death before you knew it,” says one of the characters in the novel—a chilling statement.

Historically, the fantastic genre in literature has served as a tool for social resistance.

Historically, the fantastic genre in literature has served as a tool for social resistance by breaking with normalcy and an established world order through a liberating approach that subverts it. At the same time, it is one of the genres that most exposes the social and cultural contexts from which it grew—such as Stalinism and other dictatorships for George Orwell’s 1984. When Han Kang, Mariana Enríquez, Margaret Atwood, and so many other women take, consciously or not, aspects of reality to represent the oppression of women or violence against them, when they decide that their characters will rebel against that, they make literature shake the foundation of a patriarchal culture, presenting a break with that established order. Whether these stories are written as dystopian scenes of hard science fiction or as psychological fiction pushing a character to their limit, they are drawing a significant audience of women and gender-nonconforming people because they represent a safe space to process for those of us who often feel bereft of tools to make sense of the world’s violence.

Translation from the Spanish