“Whipped by the Angel’s Wings”: French Writer Marc Alyn at the Pinnacle of His Career

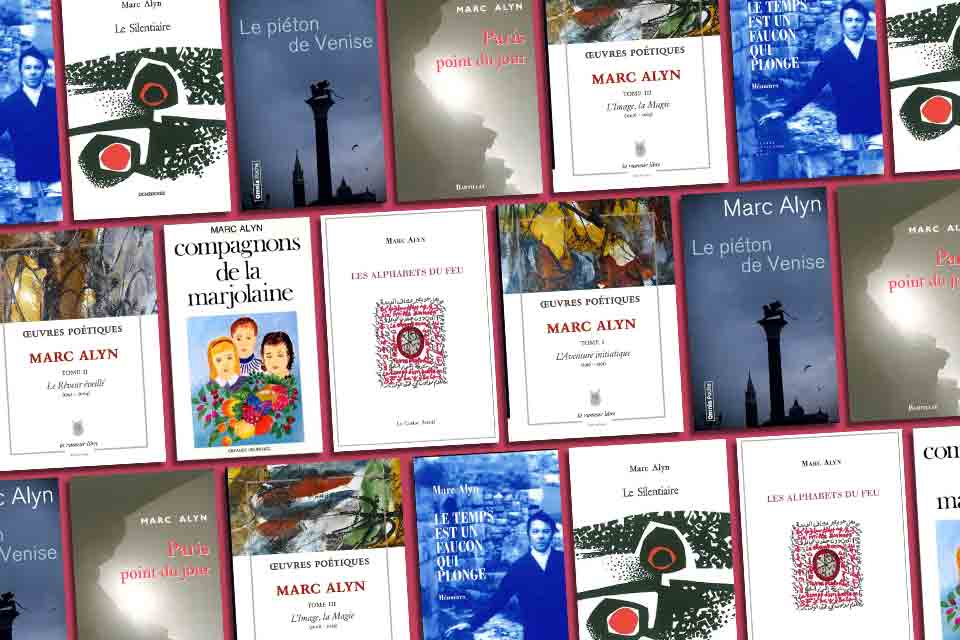

The year 2025 has been a remarkable one for French writer Marc Alyn (b. 1937). First, La Rumeur libre published his three-volume collected works, totaling nearly 1,500 pages. On March 27, during Le Printemps des Poètes at Paris’s Batignolles Library, the book’s launch was fêted by a concert of “Rêves secrets des tarots” orchestrated and sung by Marie-Hélène Dupêcher. On June 14, at the Brasserie Lipp on Boulevard Saint-Germain, an afternoon gathering honored the publication of Gwen Garnier-Duguy’s study of Alyn’s work. And on October 1, the Société des Gens de Lettres will name its main prize the Grand Prix de Poésie Marc Alyn. As of 2025, Alyn has been writing for seventy-one years, a remarkably long writing career. The following retrospective is an attempt to summarize a lifetime’s worth of work, both rich and varied.

The Importance of Childhood

All critics agree about Marc Alyn’s language skills. Bernard Fournier talks about “antithesis, sound effects, alliterations and assonances, inventive word- and image-play, and figures that enliven the mind and propel the poem forward.”[1] Such techniques are more than poetic strategy. They are like a child’s wordplay that brings forth the creative innocence of comptines, the ancient art of nursery rhymes and dancing riddles; their playfulness is that of the beginning of life. Carl Young’s phrase—“your inner child is your soul”—fits Alyn perfectly.

The poet’s childhood, as recounted by himself during a series of interviews with Marie Cayol who was the first to probe his work, was filled with word games. They begin with his first and middle names, Alain Marc (Fécherolle), inspired by his mother’s infatuation with the evil character of Fantomas created by Marcel Alain, a name that the poet eventually fashioned into his pen name. No doubt the rich literary landscape of his hometown of Reims—as well as his family that originated from the Champagne–Ardennes region and embraced a European awareness common to the region since World War I, in addition to his father’s profession as a bookseller—contributed to his proficiency with words. “My father’s house was built of books that dialogued with the sky,” remembers Alyn.

Alyn likes to say that “he was born in books.”[2] With a father who owned a bookstore and was a voracious reader, Alyn had access to a vast body of printed work. Words became his home, writing his passion, discovery his goal. Fournier discerns in Alyn’s adult poetry traces of an eclectic variety of past writers and poets. From his voluminous book culture, Alyn harvested the phrases, images, and techniques that most resonated with him, using them throughout his entire life’s work, producing effects not unlike those of the segments of a disco mirror ball. This is a distillation of iconic literary phrases, concepts, and images as well as a passion for grasping the universe in all its dimensions, from the minuscule to the cosmos, rather than a “parody,” as Robert Holkeboer, the reviewer of Infini au-delà, inferred.[3] Early reviewers of Alyn missed his desire to be “a word, a hyphen towards the Poem, the only habitable house for the ontological human being.”[4] They also missed important themes in his work.

Words became Alyn’s home, writing his passion, discovery his goal.

As a child, Alyn was fascinated by the morning sunrise as the promise of all things new, of a new beginning, a new birth. Later, he discovered the Orient through Algeria, Venice, Yugoslavia, Greece, and the Levant. The passing of time was a constant presence in his life; every physical voyage was paralleled by travel through time, leading him back to the ancient history of the eastern Mediterranean world. In so doing, he was not only deconstructing linear time but the straitjacket of the modern, industrialized, materialistic Western world in favor of a reconstruction from inside in which his relationship to nature was essential. Alyn’s symbiosis with nature was the corollary of the deconstruction of linear time; with his organic view of nature, he was also deconstructing the postmodern theories and returning poetry to its original form—of breath, chant, spoken performance. This iconoclastic and cosmic dimension of his work was truly revolutionary and freed poetry from its “convenances” (proprieties) decades before it became fashionable.

Having read a great variety of genres, Alyn practiced more than one. Besides poetic craft such as oxymorons, alliteration, assonance, counterpoint, striking images, wordplay, and unexpected detours of thought from a single word,[5] he practiced prose poetry, aphorisms, literary essays, prose, adaptations (not translations), newspaper chronicles about poetry, art criticism, administrative and editorial reports, memoirs, poetry for children, bringing a sense of rhythm and tone to his poems that resulted in several of them being put to music.

If one were to weave a tapestry from the threads of Alyn’s work, one would discern the orderly warp (the writing genres) through the shapes and colors made by the weft (the different works over time and their themes). He has done this while being a writer and a poet, an organizer of artistic and literary events and festivals, a founder of many poetry journals and associations, a conferencier, a poetry collection editor, and perhaps, most importantly, a discoverer of talent.

Very early on, Alyn accepted reality as an illusion that can be magically transformed by imagination. He remembers childhood rainbows of which he said that “sunshine was raining.” His was an early experience of poetry before culture and before reading. “We are born Surrealists,” says Alyn to convey the notion that poetry exists before its normalization and codification through school programs.[6] Another early experience that shaped his reaction to reality—and perhaps some defense mechanisms as well—was his experience of hunger, fear, exile, and death during the dark years of World War II, when heart and hearth were destroyed.

Childhood thus formed the matrix of Alyn’s major poetic themes: repeated escape into dream and imagination, the transience of all things, constant visual watchfulness (l’oeil), a keen sense of time, and a love of the night, perhaps born during air-raid confinements in the vin de champagne caves. This love for the night persisted; “this locus of all fears, the sanctuary of monsters, metaphors, marvels, led the watchers, the mystical or poetic awakeners caught in the fabric of the absolute to the heart of things.”[7] The night was the key to contemplation, to which Alyn was prone from an early age. Of his oldest memory he said:

I inhabit in my dreams a doll house furnished with game tables, sofas, minuscule mirrors. Books cover the walls but each is a closed door. From time to time a nightingale slides its beak through the window. When it rains, the roof tiles sing terribly, then the sun hunts each object to the remotest corners like an escargot fork emptying a shell. And these small paintings on the walls, miniatures of immense battle scenes! Giants walk by without seeing anything, fortunately neglecting this butterfly-sized universe.[8]

And also:

Every photograph is a glossy paper cemetery. Solitary child, prey to the imaginary, I had very early on the revelation of death’s devouring universality . . . death proved inexhaustible. . . . Poisoned rose bushes espied our coming to assault us. This mug behind the window at dusk, who was it? A dog bite / dogged death [morsure / mort sûre]? Words grew in me like mushrooms, adding playfulness to terror without moderating my intoxication. Everywhere resounded the threatening rumor of time: the ticktock of the programmed countdown of each life, an infernal time-delay machine in a safe without a key.[9]

Keenly aware of the poet’s role as a link between reality and imagination, mesmerized by the immensity of language, caught in a quixotic search for absolute poetry, and pressured by the ticktock of time, the adult poet evolved into a disrupter of things. Believing in the eternal possibility of rebirth/new beginnings, he cent fois sur le métier remet son ouvrage with a child’s heart and a weaver’s patience. Fournier likens the dual nature of his words to “the Hebrew sheol of artificial paradises” (i.e., the underworld of the dead), a morally neutral place of shadows and silences that is overcome by the surging of new words.[10] His obsession about the twin dualities of creation/destruction led him to experience each new beginning as the work to be destroyed, the fire to be burned, creating a closed loop:

Would there be, says the scribe, one loose word

in the labyrinth of an immense sentence

that upsets the book’s meaning

by erring

between the lines?

like these minuscule verses

that sometimes rise from the depths of the page

devouring the spirit with the fiber.

I imagine it thus: a parasite word condemned

to live in the margin

despite a carnage of syllables.[11]

Alyn’s obsession about the twin dualities of creation/destruction led him to experience each new beginning as the work to be destroyed, the fire to be burned.

Thus, the Scribe receives images that have the fragility of mystical visions. Images, says Alyn, are primordial. His wordplay image-magie (image-magic) says it all: “most often, the image was but a torn curtain of mirages through which filtered, here and there, the wild splendor of the world, which the eye of depths—nearly dimmed by loneliness—received as incandescence or solar host.”[12] Sur-realism has become the natural state of seeing. Together with fire, night and nature nourish the poet on a quest for his poetic home, incessantly walking toward this “elsewhere” where he will finally rest. Poetry was “the spark that revives the soul,” “solar illuminating speech.”[13]

Poetic Debuts, 1954–1962

Alyn did not wait long before acting on his poetic bent. At age fourteen, he created the literary magazine Terre de Feu in his hometown of Reims; in 1954 the Cahiers de Rochefort published his first poetic brochure, Rien que vivre: poèmes, an eleven-page chapbook that he dedicated to and sent to Alain Bosquet.[14] Among his Rémois contacts was Roger Caillois, with whom he maintained a lifelong friendship. A few years later, on his twentieth birthday, he won the 1957 Max Jacob Prize with his first poetic volume, Le Temps des autres. A volume of poems in prose followed almost immediately, Cruels divertissements (1957). Both volumes received wide acclaim.

Settling in Paris in 1957, Alyn was immediately accepted by a prestigious literary coterie: Elsa Triolet, Alain Bosquet, Robert Sabatier, Tristan Tzara, Jean Cocteau, Pierre Emmanuel, Anne Hébert, Angèle Vannier. Undaunted as only youth can be, Alyn answered Bruno Durocher, a Polish poet-survivor of the death camps, who whispered in his ear “I’ve met God!” with “How is He doing?”—upon which he was promptly hired as secretary of the Editions Caractères, which Durocher had founded.[15]

His Parisian literary life had barely begun when war intervened for the second time. He was summoned for military service, spending several months learning medical first aid and serving as a secretary at the Ministry of War in Paris. During this time, his poems were recorded by actor Jean-Louis Trintignant and sung by actor and pop singer Serge Reggiani in a new collection created by Pierre Seghers.[16] In Algeria, where Alyn was deployed shortly after the outbreak of the war, he served as an ambulance driver before returning to Algiers as staff member of the military newspaper Bled, where he and a host of young authors who would later make a name for themselves cut their teeth on journalism. Refusing to report on the war, Alyn wrote exclusively about cultural matters, using the newspaper columns to publish antiwar songs by Boris Vian and himself. During a three-day furlough in Paris in 1959, he married Jacqueline-Claude Hamel, a painter and illustrator who took the pen name Claude Argelier, and signed copies of his new book, Brûler le feu. In all, Alyn served thirty months in the military. It was in Algeria that he read Arab poetry for the first time.

Subjected to such extraordinary psychological and cultural dissociation, Alyn was nonetheless able to maintain continuity in his literary career. Before 1960 was over, Seghers published Alyn’s study of François Mauriac, his mentor and indefectible friend, in the collection Poètes d’aujourd’hui. After his demobilization, he and Claude settled in the new northern suburb of Aubervilliers, where Paul Eluard’s father, a real estate mogul, had entrusted his son with naming the streets. Alyn gleefully noted that this exile to an “affordable” suburb was more than compensated by the presence of a surrealist pantheon on every street corner, including a “Baudelaire-bar.” Soon, Raymond Audy, with whom he had served, got him acquainted with T’ang Haywen, a Chinese-born painter with whom he developed a lifelong friendship and about whose work he wrote an entire volume of poems, calling him a “calligrapher of the invisible” and a major modern Chinese artist:

An immobile traveler, T’ang espied the visible world like the insect that adopts his environment’s color and form, unnoticed to better safeguard his irreducible singularity. Art of borders, of the ultimate, delivering a unique view of the beyond from the frontier region. Levitating scribe bent over his colors, his brushes, and his dreams, Haywen captured the sky through his eyelashes. From being a figurative painter, he evolved toward abstraction, favoring the shadow rather than the thing, without negating the light: thus were born these lagunas of the end of the world where black reeds shake under the twirling sea winds.[17]

More importantly, perhaps, in 1961 Pierre Seghers sent Alyn to Slovenia (then a Yugoslav republic) to prepare what would become the first-ever French presentation of its kind, an Anthologie de la poésie slovène (1962). Alyn recounts in his memoirs his wonderment before the landscape and the culture of Slovenia. This first trip kindled his passion for Venice, where he would sojourn thirty times during his lifetime and about which he wrote two books.[18] It also introduced him to the “other” Europe and to the Bogomils, who for him were a door to the Orient. And it was another first for Alyn, who tried his hand as a translator. Surrounded by a team of Slovenian professionals who provided him with an initial, literal translation, he created

a French formulation in harmony with the atmosphere particular to each poet and each text. The music of the Slovene sentence (of which Stendhal said that it was a song) preceded me, guided me with its mysterious vibrations where the mountaintop air reverberated. This initial pleasure was a prelude to the complications of prosody, to the nuances, to the often-insurmountable difficulty to unify the syntaxes in hopes of reaching, not a servile and vain imitation, but a new poem that kept the trace of its origins.[19]

Topping off all these dizzying activities, Alyn published his third poetic volume, Les Délébiles, in 1962.

Whipped by the Angel’s Wings: The Uzès Years, 1963–1972

By then, Alyn had become a master multitasker. He excelled not only at writing but at reviewing, analyzing, editing, and especially organizing associations and events. His writing featured poems, prose poems, essays (the work by which one discovers one’s own language), and poems for children, in a demiurgic play with words. His hunger for achievement was supported by the boundless energy of youth but perhaps also stemmed from an attempt to cheat time and force the world into his words. He needed a hiding place that would provide him with the sort of escape he had loved since childhood “when reality was squeezing me too hard.”[20] Alyn, who never burned bridges, had the ability to exist comfortably in several realities simultaneously. After the Reims/Paris life and the Paris/Reims/Algeria life came the Uzès/Paris/Reims/Slovenia life. Alyn’s voluntary “exile,” in fact, was no exile at all. He left the “literary world” of Paris (which he considered a vipers’ nest) for a “wondrous exile.”[21] The Alyns were part of a cultural decentralization movement away from Paris that was taking place at the same time three hundred kilometers away in a Mediterranean village, Saint Paul de Vence, where artists and writers such as Jacques Prévert, Marc Chagall, James Baldwin, and Witold Gombrowicz found home, inspiration, and fellowship; the Maeght Foundation inaugurated in 1964, the nascent film industry, and the nearby Cannes Film Festival had a profound impact on the entire region.

The young couple moved in 1963 [Alyn in his memoirs says 1964] to the southern region of France, Occitanie, near the Roman city of Uzès, not far from the Pont du Gard and Avignon, the heart of Huguenot country. In this decade of urban renewal that followed the 1962 Malraux law for the protection of endangered cultural sites, the glorious past of the city and its economic importance as a center of the silk industry were revitalized. The property where the couple settled, le mas des poiriers, was an old ramshackle farmhouse with high romantic appeal; the nights were famous for their view of the skies, as noted by the seventeenth-century playwright Racine, who during his six months in Uzès declared that its nights were more beautiful than the Parisian days. Besides André Gide who vacationed there until 1893, at his father’s birthplace, the region had a rich literary past, from the troubadours to Jean Paulhan and many others whom the extraordinary landscape captivated. The Gard Department and Haute Provence in general were a place frequented by a host of literary and artistic figures and had perhaps the highest number of publishing houses in all France.

In this place that Maurice Barrès called le pays de l’Écriture (the writing country), Alyn found a provincial calm perhaps reminiscent of his Rémois youth. The first decade at the mas represented a very fertile creative period. There, Alyn found the infini au-delà and opened his oeil imaginaire under a shining night canopy. In Uzès, he quickly found new grounding yet was “elsewhere” at the same time. This gave him the opportunity to process new impulses and to broaden his presence on the literary scene in extraordinary ways, notably as discoverer of talents, creator of cultural gatherings and associations, administrator, editor, and reviewer. Uzès was the trampoline that would launch his next major works.

This place—Uzès—that Maurice Barrès called le pays de l’Écriture marked a fertile creative period for Alyn.

Alyn remained extremely busy and was far from being forgotten by Paris. Indeed, the number of individuals who continued to support his work and their prominence in French literature is astounding. François Mauriac remained his main mentor in Paris, opening to him the columns of Le Figaro. Alyn befriended numerous local artists and writers of the Gard. Some, like Pierre Seghers, Jean Paulhan, René Char, Georges Braque, Pierre Emmanuel, and Jean Hugo, had become Parisian glitterati, while others gained fame as true méridionaux such as Pierre-André Benoit, François Nourissier, Mario Pressinos, and Pierre and Marie Cayol. There were also adoptive Occitans such as Lawrence Durrell, who collaborated on radio programs with Alyn and published a book of his “dialogues” with the poet.[22] All visited the mas des poiriers as neighbors.[23] Alyn also enjoyed the support of the Marquise de Crussol d’Uzès, and his dinners and literary soirees gathered brilliant company. There were glorious years of exhibits and poetry readings in the entire region, as far as Thonon, Annemasse, Manosque, and Nîmes.[24]

Alyn finished penning his autobiographical novel Le Déplacement after moving into a dream house that renovations soon turned into a heavy financial burden. A pen in one hand and a shovel in the other, he listened to France-Culture’s radio broadcasts in order to send reports that George-Emmanuel Clancier, the French radio and television general secretary for programming, had asked him to write. Supported by Mauriac and published by Flammarion in 1964, Le Déplacement’s success resulted in Le Figaro entrusting to its author the newspaper’s weekly poetry reports, a job Alyn held from 1964 to 1978. In 1966 Flammarion offered him the leadership of a new poetry series that he led until 1970, publishing so many quality French and foreign poets that it was dubbed the “premier” poetry series in France by Robert Sabatier. In 1968 he published Nuit majeure, which received the Prix international Camille Engelmann in 1971. He had by then quite a cabinet d’écriture:

In a room whose floor was made of heavy terracotta tiles, on the second floor of a building once dedicated to sericulture, I had arranged a nest, a hiding place similar to the refuge where the magpie piles up her loot. Books surrounded me, vigilant and subtle sentinels. There, I had my summer balcony with a view on Eden’s orchard: plum trees with their blue fruits, pear trees with their tangled branches, and even a palm tree whose trunk had a reddish plush covering. In this place where once a legion of bombyx, fed with white mulberry leaves, was spinning silk before being smothered inside the chrysalis at the moment of its metamorphosis into a butterfly, I was writing or took flight in vast readings. Poetry, history, religion, kabbalah—no form of knowledge threw me back. . . . I was sure that a door was hidden behind the tight columns of books on the library’s shelves. Host of the silkworm factory, I unfurled the translucid thread of a sentence sewn of silence.[25]

Alyn’s association with Pierre Seghers remained strong. Having discerned a major figure of European modernist poetry in the Slovenian poet Srečko Kosovel (1904–1926), who was being published in Slovenia for the first time in the mid-1960s, Alyn proposed and Seghers accepted a new volume for the series “Poètes d’aujourd’hui.” Under the title Kosovel, the volume was published in 1965, and once again Alyn’s adaptation of Kosovel’s poems was an editorial success. A second volume of Slovenian poetry, Anthologie de la poésie slovène, was published in 1971. This caused Alyn to make several trips from Uzès to Croatia and to immerse himself in the culture of this “door to the Orient.” Alyn also availed himself of a publishing house closer to his birthplace and published a volume of Croatian poetry with the collaboration of Croatian translator and literary critic Zvonimir Mrkonjić, in the Cahiers de la grive, a periodical founded in 1928 in Charleville and famous for publishing Rimbaud.[26]

One outgrowth of Alyn’s interest in modernist Slovenian poetry was a new administrative endeavor of great scope. In March 1969 he created the Association Culturelle Actuelles Formes et Langages with his wife, specifically designed to accompany an impressive exhibit of contemporary French artists’ paintings at the French Cultural Center in Ljubljana. Shortly thereafter, he signed a presentation of the work of their friend PAB [Piere-André Benoit], a native of Alès, for an artist’s book that was published by the French Cultural Center of Ljubljana.[27] He repeated this feat in the spring of 1977 with a PAB exhibit at the French Cultural Institute in Rome.[28] Six years later, the Club Actuelles Formes et Langages was created, followed in August 1978 by an initiative called Action poétique audio-visuelle.[29]

A third work on Slovenian poetry, Nota Bene, cemented Alyn’s reputation as a worldly personality. It coincided with his first literary evenings/debates to which he invited friends and neighbors, first at the mas, then in Uzès, complete with the participation of numerous internationally prominent or soon to be prominent publishers, poets, and artists to his new venture, the Actuelles Formes et Langages publishing house. Thus Alyn enriched local cultural life and pioneered a formula that united literary, poetic, and artistic encounters.[30] Not unlike Giono’s tree planter, Alyn tirelessly planted literary magazines, associations, and encounters, long enough to watch them germinate and blossom. He befriended Robert Morel, a publisher established at the Jas du Revest Saint-Martin, who published his La Nouvelle poésie française in 1968. He wrote a book entitled L’Oiseau-Oracle, also published in Uzès in 1971 with illustrations by Claude Argelier. The book was about the local owl or effraie, to whom Alyn would dedicate many poems. Most of those books were bibliophile books (i.e., artists’ books). Published in very small numbers, from ten to one hundred copies, today they are practically impossible to find.

Alyn tirelessly planted literary magazines, associations, and encounters, long enough to watch them germinate and blossom.

The Uzès years were lived to the fullest. Even if Alyn felt that his rage to love and his passion for illumination were yet unfulfilled,[31] he published two major poetic volumes during this time, Nuit majeure in 1968 and Infini au-delà in 1972, which promptly received the Prix Apollinaire. In fact, the citation by Jean Giono chosen by Alyn to accompany his memories of the Uzès years says it all: “Blessed are those who walk in the furious whipping of the angel’s wings.”[32]

Lebanon and Love, 1972–1976

Soon, more international travels awaited Alyn. After Venice, Croatia, and Greece came Lebanon. In the early 1970s, Alyn knew the Lebanese francophone cultural scene well, and he had heard of the renowned Baalbeck international theater festival. His work as poetry critic for Le Figaro had brought him voluminous mail and forged new friendships, including Hector Klat, who invited him to give a series of conferences in Lebanon with an exhibit in Beirut of the poèmes-objets that Alyn had made with Claude Argelier and in which they had integrated art and text. Thus Alyn landed in Beirut with Argelier and Infini au-delà. There, he met a beautiful, dark-haired young woman in whom he recognized one of the hieratic figures of Ravenna, called the protector of images, and whom he later described as “woman-amphora laden with wisteria and mint / a second of my life that the infinite barely filled / forest that I held in my hand like a nest.”[33] It was Nohad Salameh.

Nohad Salameh was the scion of a genteel Lebanese family. The daughter of the poet Youssef Fadl Allah Salameh, she grew up in a cultured francophone milieu, the multilingual and multicultural environment of her native Baalbeck. She had deep attachment to the multiethnic roots of Lebanon and a deep appreciation for the past. As a young adult, she worked as a cultural journalist for the newspaper Le Réveil, wrote poetry, and worked on several anthologies of Arab love poetry. She was a liberated woman in the best sense of the term, espousing a woman’s fulfilment without renouncing her full femininity.

During this first trip, Alyn visited many sites, notably Byblos, where he became the “traveler of the supernatural” and “the healer of words” who “revived the necropolis of words.” He later described this trip as an “initiatory illumination.” It was also a step into the unknown. Alyn wrote to Salameh several years later that his friends did not recognize him upon his return to France: “Something had been triggered inside of me, something like a divinatory wingstroke.”[34]

Four years later, in 1976 [Alyn says 1975], Alyn saw Salameh again at a literary conference in Baghdad, then in late fall she was invited to Uzès. During her brief stay, Alyn composed the first poem of the volume Douze poèmes de l’été, acknowledging the impact she had had on him:

I was the concave form of myself, the imprint

of someone forgotten who remembered to be

from time to time, like the fossil leaf

in the coal relives in its dream the forest. . . .

Summer came. Bird-shaped foam alit on my fist

at noon, uncurling with its beak

every finger of my hand. Like a diving falcon,

summer had come to surround me with its perfect sphere.

Stained by shadows and snow at the sun’s zenith,

closed like bark and smooth as a wing,

free in my extreme exile, I was, long enough for a book,

the dizziness that throbs at the temples of summer.[35]

Salameh and Alyn stayed in Paris for a couple of months and declared their love for each other. Alyn credited her with reviving his will to write, saying:

In only one month, I wrote a volume of poems for children, translated texts of Jure Castelan (a great Croatian contemporary poet), and revised the manuscript of a new volume entitled The Dictionary of Travels that had languished in my drawers for years. . . . Add to this an important correspondence, the correction of galleys of several journal issues, and you will have an idea of the breadth of this work. Tomorrow I start to write the chapter about Mauriac for the collective homage entitled Génies et réalité published by Hachette; I have four days to rewrite a text of about thirty pages.[36]

His work now resembled that of the weaver assembling “the thousand threads of this dream of language, the analogy where meaning and sound tremble while marrying one another.”[37]

Alyn’s work now resembled that of the weaver assembling “the thousand threads of this dream of language.”

Alyn’s multiple activities continued: his regular columns for Le Figaro and his many activities as festival organizer left him little free time. Yet, with Salameh still in Paris, they made important decisions. Salameh was serious about marriage, and they discussed the feasibility of two poets living together. By year’s end, it was decided: they would be together. Alyn also acted as an editorial adviser for Salameh, who sent him her handwritten poems. He typed them and made recommendations, calling her “my student” but also “my Berenice” and predicted a fabulous future for her as a poet.

Of their relationship, he said, just before Salameh left for Lebanon in early 1977, “our names are from now on written in the form of a unique word, all jambs tangled in the italics of fate.” He suggested that they both had given birth to each other and that their reactions were symbiotic. And he urged her to be “the good conductor thread of my energy issued of the nuclear centrals of the Word. It is a white magic similar to the foaming coal of the rivers, the moving force of the cosmos.” This meant a return to new beginnings where the inevitable present was now telescoped from the most minute amount of time to its cosmic dimension, reminding Alyn of the nuclear dance of atoms into infinity.[38]

Alyn concluded their time together by saying, “toward what fabulous fusion are we walking? Our roads meet at the center of our hands . . . you double my life while I lengthen your fate line excessively.”[39] Alyn set about preparing everything for their permanent life together that would be “a feast and not the fabric of sadly repetitive problems.” After asking one last time, “Will we have a life to share together?”, Alyn confided that he “wanted to clear as many things as possible to return to writing a great book.” His next poetic volumes were indeed dedicated to Salameh, whose love provided inspiration for several years. He credited her for reviving his passion for writing, saying “Poetry is the Word’s laughter, its voluptuous song—and this laughter terrifies death.”[40]

Their brief time together was followed by dark years, which they both compared to a mystical initiation. The devastating war in Lebanon kept them apart for a decade without seeing or hearing from each other. Alyn did not know if Salameh was still alive or whether she was married.

Life on Hold, 1977–1987

If Alyn had worked hard to reach a minimum amount of comfort at the mas des poiriers, life in Uzès after meeting Salameh lost its appeal. Alyn called his abode “a godforsaken hole” where he lived “like a dead man.”[41] True, distance and cost made it difficult for him to travel to Paris often, but one senses a renewed restlessness and a desire to escape that only grew with time. Still, he remained busy in Provence with all kinds of writing. Lawrence Durrell sensed the transformation of his writing: “In Alyn, who is also a splendid critic, one finds the evident lines of a great personality that is shaping up, without haste. One feels that one can count on him, that he will reach the pinnacle of his art.”[42]

Soon, tragedy struck. Alyn lost both his parents in 1979. He described this period thus in his memoirs:

Orphaned at an age where it is more common to be a father, I felt that I benefited from an extended childhood. I felt all of a sudden such a need for freshness, for innocence, that—from which forgotten layers?—a plethora of fabulettes, chantefables or chantemuses (so called by Robert Desnos) intended for a very young public not yet contaminated by the Cartesian spirit and the cult of the Goddess Reason spontaneously surged from me. In these years during which I eschewed high writing, accompanied by sharp cries and bitter bat wings, I elected to be reborn amidst an art naïf issued from comptines, berceuses, and formulettes of the collective memory that, in the end, has as its mission to sharpen the mind and sharpen the perception of language. My books L’Arche enchantée, Compagnons de la marjolaine, and À la belle étoile, without forgetting Nous, les chats, were the fruits of this late spring; I owe them the singular happiness of being presented in school programs, learned by heart, recited, set to music, and sung for several decades now. Thus does one accede to the dubious honor of being a "classic": an author studied in the classes, altogether familiar and anonymous.[43]

Even though Alyn had worked on a book for children since 1976, he developed this genre “whose apparent simplicity hides complex mechanisms” in the next decade. He liked the challenge of breaking into a new market. It was perhaps the one time when he came closest to being published by commercial presses. Besides, the prospect of financial reward meant financial autonomy, so he was quite excited about it.[44] Alyn’s books of poems for children, written between 1979 and 1989, were read and taught in literature classes.[45] All these works were published in modest printings by small local publishing houses of the Gard.

Alyn’s love for cats also turned into literature. He conceived his first book about cats, which he had loved since childhood, in Uzès, where he owned a female cat named Isis. In all, he wrote three books about them. The first one, illustrated by Claude Argelier, was published in Uzès in 1986. The other two were published after his return to Paris; the third one, Monsieur le chat (2009), received the twenty-seventh Prix des 30 Millions d’Amis. Its subtitle, “For children seven to seventy-seven years old,” is emblematic of the poet’s deliberate youthful and premonitory attitude, because his poetic career would last this long.

Just before leaving Uzès for Paris in 1987, Alyn created the “Poetry Days” at Lascours Castle, in Laudun near the ancient Roman city of Orange, an enterprise that he would lead for the next seven years as the Lascours Academy. This initiative would be followed in 1995 by the media library Marc Alyn in Roquemaure, within the activities of the Association of the Friends of Marc Alyn, on the theme of poetry and visual art.[46]

By 1987, Alyn had reached le mitan de ma vie, the middle of his life. He felt that what he had published was only the prelude to his future work. Now Uzès was squeezing him too hard, and Paris became the new hiding place. Alyn mentions his delight about “reliving his twenties” and being a flâneur in the Bastille-St. Paul neighborhood of rue de Lesdiguières.

Alyn left Uzès definitively in the spring of 1987. In October of the same year, he unexpectedly ran into Salameh at the home of poet Claire Laffay in Sceaux. Salameh was in France to proof her new poetry volume, L’Autre écriture, published by Dominique Bedou. At this time, they made serious plans for their future life, with Salameh feeling that life in Lebanon had become too dangerous and literarily isolated. They spent the holidays in Beirut, where Alyn wrote Le Livre des amants, in circumstances that he described as “being at the end of the world and at the very end of myself,” seeing the book as a victory over war-induced death. Alyn also described the state in which he found himself as a difficulty to be borne, an obsession with “searching obstinately the other side of things,” calling himself, “the inexhaustible child that I hosted deep within myself.”[47] The book was published in Beirut, literally under the bombardment, and crowned with the Grand Prix de Poésie by the Société des Poètes français, thirty years after the Prix Max Jacob.

Separation only made Alyn’s love for Salameh grow. In the preface to the original edition of Le Livre des amants, he wrote of his arrival in the harbor of Jounieh in December 1987:

In the cold of this crystalline dawn, as I crossed the quay etched by salt, a frontier similar to the Other World’s, I had the violent, dazzling revelation of the forever indivisible, consubstantial character of desire and the Word. Crazy love identified itself with the Graal opening the entrances of all the labyrinths of the universe visible and invisible: the key allowing, not to flee, but to dig deep into the heart of the Dedalian labyrinth with the intention to get lost in it without return.[48]

In Le Livre des amants, Alyn wrote one of the most beautiful love poems of all time:

Take me to Writing, to the source where words are born:

the place where the future language eternally cascades!

Take my hand, we will go together in the twin shadow of

nimble words that, like us, leave their footprints on the sand.

Open the cage at the dawn of day, and may speech flee

to make love, free in the azure, in its flight.

I inhabit a lost alphabet, far away in an old poem

in a book that is no longer read . . . Join me if you love me.

From each letter of your body I want to embrace the jambs,

full and narrow, your wild curls as you run and soar.

I find myself in an antique age. What crouching scribe torments me?

Words cast down the well like prayers to gods of thirst and acanthus.

Allow my lips to glide along your long-limbed syllables,

watch as I look at you through the ink of exile.

I carry within me galaxies, the mind’s thunder, the exhilaration

of the Writing created with my voice, lizard in the master beam.

How many future spaces are ripening like heavy grapes on the vine,

in the unanimous and naked night where a new spark surges?

May your language at last enliven the abstract sounds that compose me

and may I be a dazzled stance at your mouth, like a rose.[49]

In Le livre des amants, Alyn wrote one of the most beautiful love poems of all time.

In the spring of 1988 another meeting followed at the international Poetry Biennale Al Marbad held in Basra. In October 1988 Alyn, who had filed for divorce (the divorce wasn’t finalized until the spring of 1989), traveled to Beirut where Salameh was torn, waiting for the publication of her next book in France, L’Autre écriture, and having made the decision to leave Lebanon. Several harrowing months in the spring of 1989 ensued, when the war took a turn for the worse. The intense bombing of Beirut in March endangered Salameh’s life and made daily life a challenge. Yet in mid-April, she was still torn about leaving Lebanon and uncertain about the future.

Their literary and poetic symbiosis was also a very concrete one, as she wrote to him at the end of November, after his return to Paris: “I eat à la Marc, I love à la Marc, and I live à la Marc.” Alyn was very busy that spring: in March, he had to prepare for a poetic evening in the crypt of the Église de la Madeleine in Paris, a speech about Robert Mallet, and a choice of poems for a conference on the theme of “The Love Poetry of M. Alyn” at the Musée du Vieux Montmartre. He was also planning the Poetry Days at Lascours Castle later in the spring and typing the manuscript of a volume entitled À la belle étoile, which he had written in Beirut and planned to present under the pen name of Philippe Brienne to the jury of the Prix Jeunesse, from which the money would help him set up his new home with Salameh. Alyn’s commitment to Salameh is seen in the fact that during one of the intellectuals’ protest marches on April 4, he applied for Lebanese citizenship out of solidarity for an agonizing country. He called her “Pygmalion,” and Salameh replied: “You are my organ player whose notes build and destroy invisible cathedrals.”[50]

By May, the Jounieh–Larnaka connection by boat was extremely precarious, and leaving Lebanon had become very dangerous. Salameh had to part with all her possessions, furniture, and books, and destroyed an unfinished volume of Arabic love poetry. She destroyed most of the articles she had written for Le Réveil since 1976; even the apartment in which she had moved had to be sold under bombardment. Alyn defined the new life that awaited her in the last letter he wrote to her before her departure:

I have waited so long for you, crossing my destiny like a fatalistic cat chasing not a goal, but a dream at the border of day and night. We are reaching a divine maturity: the flower is but a passage: one must know to wait and reach the fruit. Together, you and I, we shall have crossed the river of fire and emerge as initiates able to overcome finitude by force of constant metamorphoses. Every form is born from pleasure, never from duty. I shall dress you in a fabric of lightning, and the work ahead of us will have the roundness of the apple. Here begin the years of embers. Who are these two, who have returned from the kingdom of shadows to testify about the greatness of life? I take your hand and we move forward on the delectable trampoline above the void. Fear not falling.[51]

On June 13, 1989, Salameh landed at Orly Airport with a few suitcases in which she had been able to pack ten books. Alyn and Salameh were married on January 4, 1990, in the Quatrième Arrondissement’s town hall in Paris.

Le Temps Partagé, 1990–Present

Alyn and Salameh were both starting from scratch in 1990. They are fiercely private about that part of their lives. Fortunately, their earlier lives are documented in several books.[52] Their thirty-five years together are known mostly through their poetic output, and can be studied from the significant portions of their personal archives, manuscripts, and artists’ books that they donated to the Carnegie Library in Reims.[53]

From their first encounter in Beirut in 1972, Alyn had divined the soul-sister he had found in Salameh, writing: “Between Salameh and me, something had opened like the Red Sea in front of the Hebrews, just long enough for a flash, a spark, then the waters had closed, leaving in our hearts only the taste of iodine and salt. We would later recover this unique fragrance in our parallel poems.”[54] Their poems echoed one another, deeply rooted in a oneness of mind, disposition, and feeling. As newlyweds, they keenly felt the consubstantiality of the Word and Desire after they started their life together.

Salameh’s career before meeting Alyn was comprised of articles published in the Lebanese daily newspaper Le Réveil, numerous essays, and one volume of poetry published in 1970, L’Écho des respirations. She received the Prix Louise Labé in 1988 for L’Autre écriture and rose to become a stellar francophone poet. Since marrying Alyn, she has published eleven out of the sixteen volumes of poetry that compose her life’s poetic oeuvre. She has received numerous literary prizes, among them the International Poetry Prize Léopold Sédar Senghor in 2020. In 2012 she published D’autres annonciations, poèmes 1980–2012, an anthology of her poems that received the Paul Verlaine Prize in 2013. The symbiosis in her and Alyn’s poetic creation is reflected in the themes she chose for some of her volumes: the importance of time and the past (Baalbek: les demeures sacrificielles, 2007; Passagère de la durée, 2010; Saïda/Sidon et Baalbek/Heliopolis, 2024), the visionary aspect of poetry (Chants de l’avant-songe, 1993), exile and perpetual wandering (Jardin sans terre, 2024), and especially her books dedicated to women who in their time were role models for the liberation of women (Le Livre de Lilith, 2016; Marcheuses au bord du gouffre, 2017; Les Éveilleuses, 2019). They shared eroticism as a spiritual, existential discipline. In Salameh’s poems one finds the same need to reflect on the passing of time, to awaken the reader, and the same love of dazzling, visionary, or incantatory images.

Alyn’s activities did not slow down: conferences, writing workshops in schools, penning Byblos, the first book of Les Alphabets du feu, in the rue de Lesdiguières love nest that he had so carefully prepared for Salameh. He called the work

a decisive leap forward in my literary travel. Between dazzlement, fascination, and return to the sources, I begin a purposeful destruction of History from the evocation of a place buried under so much past that one does not know from what century to grab it. Cemetery of the alphabet, this corner of the earth symbolizes in my eyes the matrix of the everlasting fecundation of the Word by itself.[55]

The cancer of the larynx that Alyn suffered beginning in 1991, which would render him voiceless for the next six years, was only ended when the trachea tube was removed in 2000. This did not stop him from proofing, at Bichat hospital, the galleys of Le Scribe errant in 1992, which deals with the theme of writing at the time of illness; depression shows “in the six poems of Calvary the symbol of the crucified Word, abandoned at the beginning of a disinherited Writing.”[56] Alyn also wrote two poetic ensembles about his illness, Parole planète and Voix Off (part of l’État naissant). And in 1994 he was awarded two prestigious prizes, the Grand Prix de la Société des Gens de Lettres and the Grand Prix de l’Académie française. Finally, he created the Société des Amis de Marc Alyn, which lasted five years (1996–2001). Beginning with Infini au-delà, Alyn had favored relatively short units of poems that were later gathered in a book. He developed this technique with his books of children’s poems. He also chose it for his artists’ books, especially the four books that he wrote in the 1990s that were illustrated by his friend Pierre Cayol. Salameh also wrote a short volume of poems that was illustrated by Cayol.[57]

Alyn’s preoccupation with time grew only more pressing with the years. Time Is a Diving Falcon, the title of Alyn’s memoirs that were released in 2018, indicates the poet’s lifelong awareness of the inexorable acceleration of time throughout one’s life. It echoes the millenarian nostalgia of tempus fugit and at the same time fiercely fights the descending darkness of old age. Time became “shared time,” enriched by the couple’s love for each other, their love for art, and their penchant for co-authoring books. In 2001 another friend, Alain Benoit, who headed the publishing house Itinéraire in the Gard, published the first book co-written by Marc Alyn and Nohad Salameh, Les miroirs byzantins. In 2024 they published a second artist’s book in the form of five poems each, richly illustrated by Bernard Alligand, that reveals them as accomplices in life and work. The artwork illustrates the tension between cosmic and earthly time, between the ephemeral and the eternal, and “transcends the linear perception of time by a game of mirrors and geometric forms symbolizing the birth and expansion of the universe in the contrasting colors of red and black strewn with silver and gold stars.”[58] This work crowns the numerous artists’ books and illustrated books created by both poets. Where Alyn says “the jagged hours make hoarse the song of the grasses,” Salameh speaks of “the mouth that bleeds from the poems.” Where Alyn talks about the “eternal time toward the shores of childhood,” Salameh answers: “time flees side by side, bottomless satchel, Medusa’s raft, toward miracles.”

Time Is a Diving Falcon indicates the poet’s lifelong awareness of the inexorable acceleration of time throughout one’s life.

The wanderer, the one who tirelessly wants to change readers’ perception of the world, has a life trajectory in the margins of conventional norms—the life of a prophet and survivor, human, all too human. Alyn has survived five major challenges: World War II, the Algerian War, the Lebanese War, a war against cancer, and the war of the past three years against macular degeneration. He imagines his late friend Pierre-André Benoit writing from his Rivières home a letter or a poem “that we will decipher later, when our eyes will open for good.”[59] Day after day he dictates his poems and revisions to Salameh and is working on a new volume that he calls “oval poetry.” Like a biblical character, Alyn’s story is open-ended. He may not get to “the heart of things,” but his footing is sure:

Where we are going, time dreams of existing, of being born and dying

endlessly, tumultuously, with waves and winds.

Liberated from form, our gestures follow us: we must

stand closer together yet

make room for them

on the dark ridge where we vacillate

between two dizzying clusters.

Where we are going, the shoreless sea unravels

its black snow slips

through ancient mouths toward

the sinewed absence that continues to beat

and to remember

in what once was its cage.

(from Délébiles, 1962)

Postscript, February 2026

Marc Alyn passed away on December 7, 2025. During the fall, two volumes of poetry were in production. In October 2025 a bilingual French-Italian volume was published, Notizie dall’altrove (News from elsewhere) (Multimedia Edizioni, 67 pp.). In December 2025 appeared the posthumous Balcon sur l’ailleurs (A view of elsewhere) (Editions Al Manar, 75 pp.), with drawings by Jean-Marc Brunet. These two volumes end a poetic career that spanned seventy-one years. The French volume is an expanded version of the Italian one, with three out of its four parts forming the text of the Italian volume. In the luminous, visionary style of Alyn’s imposing corpus, they retrace the progression of the poet’s lifelong journey with words. Navigating between the poet as the link and the poem as the locus, the volumes constitute a poetic biography that shares emotions, sensations, visions, and images that have lost none of their fiery power. The first part of Balcon sur l’ailleurs, entitled “La césure émerveillée” (The amazed caesura), sketches the portrait of a young man inhabited by the Word and his relationship with books that “spelled him” (22).

In the second part, entitled “Balcon sur l’ailleurs” in the French edition and “Territoires du dedans” (Internal territories) in the Italian edition, we read:

That is where began the nuptials

of the Voice with the Text

the nuptials of oblique

twilights

striated by azure.

(p. 36 of the French edition, 22 of the Italian)

The word oblique represents a new theme in Alyn’s vocabulary; it designates the poet’s passage through a world in perpetual motion, his sliding through impermanent cracks and openings, in a cosmic nomadism that returns the poet to the center of himself. That place is the verberie, i.e., the birthplace of the poem, with which he is now finally united (p. 56 of the French edition, 44 of the Italian). No term could better sum up the focus of Alyn’s final works.

The final part of both volumes is dedicated to the night, Alyn’s primal source of inspiration. The word nyctalope occurs several times, almost as a prerequisite for poetic creation. It is entitled “La Nuit sur ses talons de neige” (Night on its snowy heels) in the French edition and “Ténèbres en cavale” (Tenebrae on the run) in the Italian edition. The slight differences in the titles encapsulate Alyn’s attitude toward a life that never stopped moving and took him to unexpected and prophetic places:

Shaded by prodigies and

dreamy itineraries, the Night snuck

through the concealed door of clairvoyance

till it reached the balance point

where the seminal flames

of the new day are birthed.

La Nuit ombrée de prodiges

d’itinéraires oniriques

s’insinuait par la porte dérobée des voyances

jusqu’au point d’équilibre

où s’enfantent les flammes séminales

du nouveau jour.

(p. 68 of the French edition, 56 of the Italian)

University of Tennessee at Martin

Editorial note: The French version of this essay, “La poésie est le rire du Verbe — La vie et l’œuvre de Marc Alyn,” appeared in Recours au poème in January 2026.

Marc Alyn and Nohad Salameh: An Official Bibliography

Co-Authored Books

Les miroirs byzantins (Alain Benoit, 2001)

Le Temps partagé, by Marc Alyn, Nohad Salameh, Bernard Alligand (Editions d’art FMA, 2024)

Complete Bibliography of Nohad Salameh

L’écho des respirations (1970)

Les Enfants d’avril (Le Temps Parallèle, 1980)

Folie couleur de mer (Le Temps Parallèle, 1983)

L’Autre écriture (Dominique Bedou, 1987; Prix Louise-Labé, 1988)

Chants de l’avant-songe (L’Harmattan, 1993)

Les Lieux visiteurs (Cinq continents, L’Harmattan, 1997)

La Promise (Cinq Continents, L’Harmattan, 2000)

La Revenante (Voix d’Encre, 2007)

Baalbek: les demeures sacrificielles (Éditions du Cygne, 2007)

Passagère de la durée (Éditions PHI/Editpress, 2010)

D’autres annonciations, poèmes 1980–2012 (Le Castor astral, 2012)

Le Livre de Lilith (Atelier du grand Tétras, 2016)

Marcheuses au bord du gouffre (Éditions de la lettre volée, 2017)

Les Éveilleuses (Atelier du Grand Tétras, 2019)

Saïda/Sidon et Baalbek/Heliopolis (Éditions du Cygne, 2024)

Jardin sans terre (Al Manar, 2024)

Distinctions

Member of the jury of the Prix Louise-Labé

Officer of the Order of Palmes académiques (2002)

Grand Prix de Poésie Louis-Montalte in 2007 for the totality of her work, awarded by the Société des gens de lettres

Prix Paul Verlaine of the Académie française for D’autres annonciations (2013)

Léopold Sédar Senghor International Poetry Prize

Complete Bibliography of Marc Alyn

Prizes and Honors

Le Temps des autres (1957, Prix Max-Jacob)

Nuits majeures (1973, Prix international Camille-Engelmann)

Infini au-delà (1973, Prix Guillaume-Apollinaire)

Grand Prix de poésie de la SGDL pour l’ensemble de son œuvre (1994)

Le Piéton de Venise, Prix Henri de Régnier de l’Académie française

Monsieur le chat (Prix Littéraire Trente millions d’amis, appelé Goncourt des animaux 2009)

Fondateur de la revue Terre de feu

Fondateur de la collection Poésie/Flammarion (1966–1970)

Membre de l’Académie Mallarmé et du jury du Prix Guillaume-Apollinaire

Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur

Officier des Arts et des Lettres

Poetry

Rien que vivre: poèmes, Cahiers de Rochefort, 8th series, 4th notebook (1954)

Liberté de voir, Terre de Feu (1956)

Le Temps des autres, Seghers (1956)

Cruels divertissements, Seghers (1957)

Jean-Louis Trintignant dit les poèmes de Marc Alyn, Véga-Seghers (1958)

Serge Reggiani dit, Marc Ogeret chante Marc Alyn, Studio S.M. (1958)

Brûler le feu, Seghers (1959)

Délébiles, Ides et Calendes (1962)

Nuit majeure, Flammarion (1968)

Infini au-delà, Flammarion (1972)

Les Dieux bleus, PAB (1975)

Douze poèmes de l’été, Formes et langages (1976)

Rêves secrets des tarots, Formes et langages (1984)

Poèmes pour notre amour, Formes et langages (1985)

Le Livre des amants, Des Créateurs (1988)

Le Chemin de la parole, L’Harmattan (1994)

L’État naissant, L’Harmattan (1996)

Les Mots de passe, L’Harmattan (1997)

L’Œil imaginaire, L’Harmattan (1998)

Le Miel de l’abîme, L’Harmattan (2000)

Byblos, La Parole planète, Le Scribe errant, iDLivre (2001)

Les Miroirs byzantins, Alain Benoit (2001)

Le Tireur isolé, Phi/Écrits des Forges (2010)

La Combustion de l’ange, 1956–2011, préface de Bernard Noël, Le Castor Astral (2011)

Proses de l’intérieur du poème, 1957– 2015, préface de Pierre Brunel, Le Castor astral (2015)

Le Centre de gravité: l’Intégrale des aphorismes, L’Atelier du Grand Tétras (2017)

Les Alphabets du Feu, édition définitive revue et corrigée, Le Castor astral (2018)

T’ang l’obscur, Mémorial de l’encre, Voix d’encre (2019)

Forêts domaniales de la mémoire, La Rumeur libre, 2023

Œuvres complètes, 3 vols., La Rumeur libre (2023), dedicated to Salameh:

Vol. 1 L’œuvre initiatique, 1956–1991. Introduction by Jean-Jacques Celly (1934–2006; 1984 graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, started publishing in 1956).

Vol. 2 Le rêveur éveillé, 1992–2004. Introduction by Georges-Emmanuel Clancier (1914–2028).

Vol. 3 L’image – la magie, 2006–2023. Introduction by Pierre Brunel (b. 1939; Normale Sup. Sorbonnard, membre de l’Institut universitaire de France, littérature comparée).

Prose

Marcel Béalu, Subervie (1956)

François Mauriac, Seghers (1960)

Célébration du tabac, Robert Morel (1962)

Les Poètes du XVIe siècle, J’ai Lu (1962)

Dictionnaire des auteurs français, Seghers (1962)

Dylan Thomas, Seghers (1962)

Le Déplacement, Flammarion (1964)

Gérard de Nerval, J’ai Lu (1965)

Srecko Kosovel, Seghers (1965)

André de Richaud, Seghers (1966)

Odette Ducarre ou Les Murs de la Nuit, Robert Morel (1967)

La Nouvelle Poésie française, Robert Morel (1968)

Norge (poète) | Norge, Seghers (1972)

Entretiens avec Lawrence Durrell, Pierre Belfond (1972) et Gutenberg (2007)

Le Diderot de Borès, Galerie du Salin (1975)

Vision sur Tony Agostini, préface de Henri Gineste, Éditions Vision sur les arts, Béziers, 1979

Le Manuscrit de Roquemaure (illustrations de Pierre Cayol), Le Chariot (2002)

Mémoires provisoires, L’Harmattan (2002)

Le Silentiaire (illustrations de Pierre Cayol), Bernard Dumerchez (éditions) | Dumerchez (2004)

Le Piéton de Venise, Bartillat (2005); livre de poche Omnia (2011)

Les Miroirs voyants, Voix d’encre (2005)

Le Dieu de sable, Phi/Écrits des Forges (2006)

Paris point du jour, Bartillat (2006)

Approches de l’art moderne, Bartillat (2007)

Monsieur le chat, Écriture (2009); Archipoche (2014)

Anthologie poétique amoureuse, Écriture (2010)

Venise, démons et merveilles, Écriture (2014)

Le Temps est un faucon qui plonge, mémoires, Pierre-Guillaume de Roux (2018)

Works for Children

L’Arche enchantée, Enfance heureuse, Éditions Ouvrières (1979)

Nous, les chats, Formes et Langages, 1986, rééd. La Vague à l’âme (1992)

Compagnons de la marjolaine, Enfance heureuse, Éditions Ouvrières (1986) [listen to a child reciting “La Planète malade”]

À la belle étoile, La Vague à l’âme (1990)

[1] Bernard Fournier, L’Imaginaire dans la poésie de Marc Alyn (L’Harmattan, 2004), 9.

[2] Marc Alyn, interview with Alice-Catherine Carls, June 9, 2025.

[3] Robert Holkeboer, review of Marc Alyn’s Infini au-delà, Books Abroad 47, no. 2 (Spring 1973): 320. Academic American reviewers of Alyn, trained in interwar French literature, entirely missed the revolutionary nature of his poetry. See Francis J. Carmody, review of Brûler le feu, Books Abroad 34, no. 2 (Spring 1960), 143. They seemed more interested in his more “academic” works such as his La nouvelle poésie française and Mauriac. Holkeboer defended his PhD dissertation, The Poetry of Marc Alyn: Introduction and Translation, at Ohio University in 1971. Holkeboer’s article on Alyn in the Summer 1972 issue of Books Abroad includes two of Alyn’s poem translated into English.

[4] Gwen Garnier-Duguy, Le Scribe en marche. Lire Marc Alyn (La Rumeur Libre, 2025), 107.

[5] Bernard Fournier has done a masterful analysis of Alyn’s poetics in L’imaginaire dans la poésie de Marc Alyn, 9.

[6] Marc Alyn, interview with Alice-Catherine Carls, June 9, 2025.

[7] Cited in Marc Alyn, Mémoires provisoires. Entretiens avec Marie Cayol (L’Harmattan, 2002), 139.

[8] Cited in Cayol, Marc Alyn, 17.

[9] Cited in Cayol, Marc Alyn, 25

[10] Fournier, L’imaginaire, 222.

[11] Alyn, “La Nuit du labyrinthe, Chant IX,” in Œuvres poétiques, 1:215.

[12] Alyn, Le Silentiaire (Dumerchez, 2004).

[13] Gwen Garnier-Duguy uses six themes to organize his study of Alyn’s work: nature, night, fire, Word, Venice, and the Orient. Garnier-Duguy, Le Scribe en marche, 9, 15, 24, 28, 33, 38. The citations by Alyn are from Parole planète, cited in Garnier-Duguy’s work on 56–57.

[14] Alyn, Rien que vivre.

[15] Alyn, Le temps, 48.

[16] Martine Lafon, “Être à Uzès,” La nouvelle cigale uzégeoise, No. 24, December 2021, 18–19.

[17] Alyn, Le temps, 95. The poems dedicated to T’ang Haywen are entitled T’ang l’obscur and were first published in 2019.

[18] Alyn, Le Piéton de Venise (Bartillat, 2005); Venise, démons et merveilles (Écriture, 2014).

[19] Alyn, Le temps, 83.

[20] Alyn, Le temps, 174.

[21] Cited in Cayol, Marc Alyn, 159.

[22] Lawrence Durrell, The Big Supposer: An Interview with Marc Alyn (Grove, 1973). French version as Le grand suppositoire. Entretiens avec Marc Alyn (Pierre Belfond, 1972).

[23] Imitating the formula of a poet presenting another poet, Les Vanneaux publishing house did publish a study of Alyn in 2012, presented by André Ughetto, a sign that the formula was still working. The list of artists and writers of the Gard region is given in Marie Cayol’s Marc Alyn, 171.

[24] Cited in Cayol, Marc Alyn, 149.

[25] Alyn, Le temps, 121–22.

[26] Marc Alyn – Zvonimir Mrkonjic, Poésie croate d’aujourd’hui (Cahiers de la grive No. 1, ca. 1970).

[27] Librairie à la Demi-Lune’s Facebook post, February 21, 2024; Alyn, Ma menthe, 85.

[28] Cited in Cayol, Marc Alyn, 151.

[29] Notes by Jean-Louis Meunier, email from Marie Cayol to Alice-Catherine Carls, August 4, 2025.

[30] Lafon, “Être à Uzès,” 12–20.

[31] For more details about these cultural initiatives, see Alyn, Le temps, the chapter entitled “Environs d’Uzès, géographie sentimentale.”

[32] Lafon, “Être à Uzès,” 20.

[33] The citation is from the volume Byblos. Cited in Alyn, Le temps, 148.

[34] Cited in Cayol, Marc Alyn, 163–68; Alyn, Ma menthe, 53.

[35] Alyn, Œuvres poétiques, 1:317–18.

[36] Alyn, Ma menthe, 78.

[37] Alyn, “Dans la magnanerie,” in Œuvres poétiques, vol. 1.

[38] Alyn, Ma menthe, 69, 76, 72.

[39] Alyn, Ma menthe, 46.

[40] Alyn, Ma menthe, 26. See also 56 and 61.

[41] Alyn to Salameh, December 13, 1976, in Ma menthe.

[42] Alyn, Le temps, 137.

[43] Alyn, Le temps, 170.

[44] Alyn to Salameh, December 13 and 18, 1976, in Ma menthe, 57, 61.

[45] Alyn, Nous, les chats, 1992; L’Ami des chats, 2008; Monsieur le chat, 2009; L’Arche enchantée, 1979; Compagnons de la marjolaine, 1989.

[46] The association published the Cahiers Marc Alyn between 1996 and 2001. Vol. 5, published in 2000, has sixty-eight pages.

[47] Alyn, Le temps, 179, 182.

[48] Alyn, Œuvres complètes, 1:331.

[49] Alyn, “Les amants de Byblos,” Œuvres complètes, 1:339.

[50] Alyn, Ma menthe, 318. Also see 337, 349–51, 372.

[51] Alyn, Ma menthe, 358. The destruction of her manuscripts is mentioned on p. 66.

[52] Salameh and Alyn’s life together for the past thirty-five years is a mystery despite the publication of their love letters, Ma menthe à l’aube mon amante, and Alyn’s memoirs, Le temps est un faucon qui plonge. A mystery despite Marie Cayol’s interview with Alyn in Mémoires provisoires. The best-known part of their lives is their work examined by Marie Cayol, who was the first to list the themes in Alyn’s creation without dissociating work and life.

[53] Both poets also made donations to other institutions. In 2014 her donation of documents created the Salameh Youssef Salameh Collection in Lebanon, at the Centre patrimonial Phénix of the Université Saint-Esprit of Kaslik. Manuscripts and documents by Alyn relating to his relations with several cultural institutions were donated to the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal in 2015. Both collections can be accessed online at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France under the heading “Gallica/Marc Alyn.”

[54] Alyn, Le temps, 149.

[55] Alyn, Le temps, 185.

[56] Alyn, Le temps, 189.

[57] Alyn, Grain d’ombre (1992), with three etchings; Carnet d’éclairs (1994), with three etchings; Les transparentes (1999), with three etchings enhanced with watercolor; Le manuscrit de Roquemaure (2002) with four lino engravings enhanced with watercolor. Nohad Salameh, L’oiseleur (2000), with three lino engravings enhanced with watercolor.

[58] Le Temps partagé. Marc Alyn. Nohad Salameh. Bernard Alligand (Editions d’art FMA, 2024).

[59] Cited in Cayol, Marc Alyn, 152.

[59] Alyn, “Où nous allons,” in Œuvres complètes, 1:186.