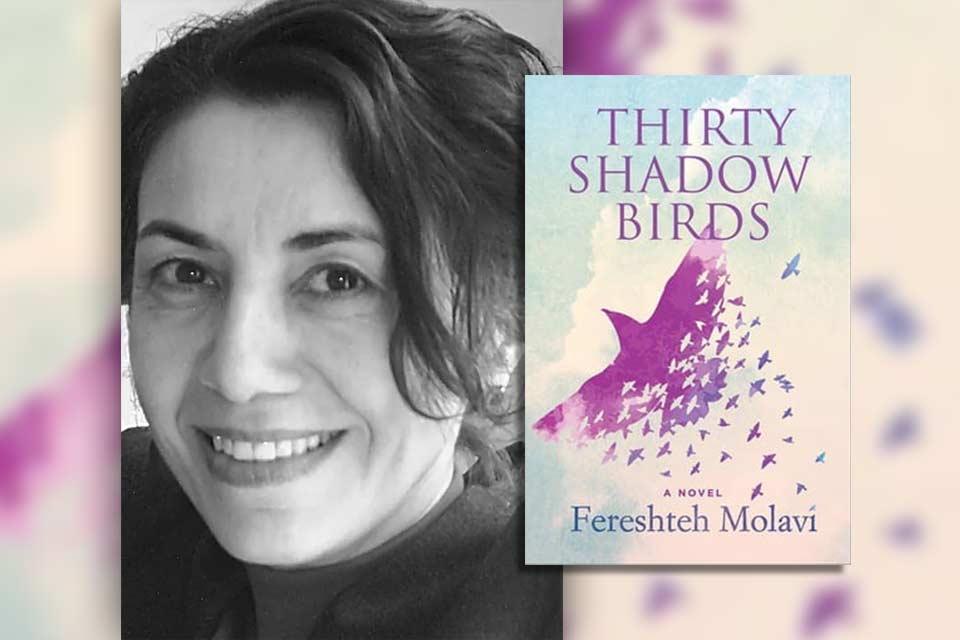

Simorgh in Exile: Reimagining Iranian Diaspora in Fereshteh Molavi’s Thirty Shadow Birds

In Thirty Shadow Birds (2019), Fereshteh Molavi constructs a literary landscape where diasporic identity is neither fixed nor nostalgic but refracted through narrative, myth, and memory. The novel’s protagonist, Yalda—an Iranian immigrant woman residing in Canada—finds herself in an unfamiliar Montréal apartment where she must offer her story in lieu of rent. This exchange, story for shelter, forms the narrative spine of Molavi’s novel and serves as an extended metaphor for the transactional and often uneasy nature of diasporic storytelling within the context of state multiculturalism, literary markets, and cultural consumption. Through its interweaving of Persian literary motifs—particularly the myth of the Simorgh from Attar’s Conference of the Birds—and a persistent refusal to conform to Western expectations of diasporic victimhood, Thirty Shadow Birds maps out a space for diasporic re-collectivity grounded in what Yalda herself calls “woodling,” the act of weaving and doodling fragments of her life into a form of storytelling that refuses closure or commodification. This hybrid mode of narration resists neat categorizations, mirroring Yalda’s own hyphenated existence as an Iranian-Canadian woman attempting to articulate a coherent self across cultures, languages, and political histories.

Molavi opens the novel with a direct invocation of a Persian matal, a folkloric nonsense rhyme traditionally used to lull children into sleep: “I have a tale to tell, with a bird as a head, with a bird as a tail. Shall I tell it, or shall I not tell it?” While such matals are repetitive and playful in their original context, their appearance in Thirty Shadow Birds is deeply defamiliarized. In Yalda’s voice, this rhyme is not a call to sleep but a demand to be heard. Rather than amusing or pacifying, the matal opens a space where urgency replaces lullaby, where voice asserts itself against silence. Its repetition throughout the novel serves as both an invocation and a challenge, suggesting that the stakes of storytelling in exile are always entangled with the question of audience, legibility, and worth. For Yalda, the telling of the tale is never an innocent act. It is a means of survival, a performance negotiated under the shadow of expectation, and a gesture toward diasporic collectivity.

The stakes of storytelling in exile are always entangled with the question of audience, legibility, and worth.

Yalda’s initial promise to recount the story of the Simorgh, drawn from Attar’s Conference of the Birds, establishes a classical frame that Molavi later reframes and complicates. In Attar’s allegory, the birds of the world undertake a long and difficult journey in search of the legendary Simorgh. When they finally arrive, they come to the realization that the Simorgh is not an external being but a reflection of themselves. This Sufi metaphor for self-realization and unity with the divine is not retold by Yalda in any traditional form. Instead, she sets it aside and chooses to write her own story in thirty chapters, using the number as a symbolic echo of the birds in Attar’s tale. Her narrative does not pursue transcendence or spiritual resolution. It traces the physical, emotional, and psychological realities of a woman living in exile, marked by trauma, maternal strain, sexual complexity, and linguistic dislocation. In Molavi’s novel, the Simorgh becomes a diasporic metaphor, not a spiritual symbol. The structure of the birds remains intact, but their journey is grounded in memory, migration, and the intimate challenges of negotiating identity across fractured cultural contexts.

Crucially, Yalda’s story is not shared within a communal or familial circle. It is written for a stranger, a puppeteer who provides her with temporary lodging and agrees to take her story in lieu of rent. His profession, manipulating shadows for an audience, becomes emblematic of how diasporic narratives are staged in host societies. The puppeteer is a cipher for the Canadian literary market and multicultural ethos, both of which seek to receive the stories of diasporic others under the guise of inclusion. Yet this inclusion is predicated on a politics of performance. The storyteller must offer a coherent, consumable narrative that aligns with the expectations of cultural difference and gratitude.

Molavi’s portrayal of this dynamic is subtle but biting. The puppeteer provides Yalda with paper, time, and space to write, echoing Virginia Woolf’s argument that a woman needs a room of her own to write fiction. But this generosity is not without its conditions. The shadow man remains unnamed, uninterrogated, and opaque. He grants Yalda the means to narrate but not the right to own her narrative. Once written, the story becomes his property to be staged, interpreted, or repurposed at his discretion. This troubling dynamic mirrors the post–Multiculturalism Act climate in Canada, where diasporic authors are often invited to participate in national literary discourse only insofar as their narratives serve the larger project of Canadian cultural pluralism. Yalda’s story, thus, is at once empowered and dispossessed, written on her terms but surrendered into someone else’s hands.

Despite this, Thirty Shadow Birds refuses to capitulate to the demand for ethnographic transparency or victimhood that often frames diasporic literature. Instead of offering a familiar tale of a veiled woman escaping patriarchal tyranny, Molavi constructs a female protagonist who is emotionally unpredictable, often unlikable, and always self-possessed. Yalda drinks, has affairs, mocks religious conventions, and actively resists her son’s decisions. Her relationship with her homeland is conflicted but not severed. Unlike the hostage narratives identified by Farzaneh Milani and critiqued by scholars such as Gillian Whitlock, Molavi’s novel does not capitalize on the spectacle of oppression. Rather, it invites readers to consider how diasporic women remember, revise, and narrate their pasts in ways that neither erase nor exaggerate trauma.

Molavi’s innovation lies in her portrayal of matals and Persian storytelling traditions as tools of re-collectivity, rather than as static markers of cultural authenticity.

Molavi’s innovation lies in her portrayal of matals and Persian storytelling traditions as tools of re-collectivity, rather than as static markers of cultural authenticity. Yalda grew up with these tales, primarily as recited by her half-sister Mati, whose performative storytelling provided refuge amid familial chaos. The matal in Mati’s voice served not only to entertain but to forge bonds between siblings living through emotional and structural violence. These stories, repeated with slight variations, were modes of resistance, humor, and survival. Unlike Yalda’s transaction with the puppeteer, Mati’s stories were not offered for exchange or performance but for communion. When Yalda later adopts the matal form to recount her own life story, she transforms it from oral performance to written narrative, from intimate kinship ritual to diasporic documentation.

What distinguishes Yalda’s use of Persian literary conventions is their transformation in the context of exile. The matal and the Simorgh myth are not simply transplanted into Canadian soil. They are reworked, filtered through the languages, landscapes, and displacements of diaspora. Molavi writes not in Persian, but in English. Yalda’s narrative is punctuated with French phrases, Canadian landmarks, and references to digital modes of communication. Her diasporic subjectivity emerges not from a preserved Iranian essence but from a syncretic process of cultural “woodling.” In this, she achieves what Hamid Dabashi has called critical intimacy, a mode of relation with one’s culture that is reflective rather than nostalgic, grounded in deep knowledge but also in distance and reinvention. Yalda is intimate with Persian culture but not beholden to it. She invokes Attar not to reproduce tradition but to claim space for her own voice within and beyond it.

Moreover, Yalda’s relationship to her son, Nader, serves as a narrative thread that anchors her storytelling in the present. Her decision to leave Toronto stems from her horror at Nader’s decision to abandon his philosophy studies and become a security guard. The symbolism here is poignant. Yalda, who fled Iran to shield her son from the violence of postrevolutionary politics, now sees him willingly entering a profession she associates with complicity in state-sanctioned violence. Her journey to Montréal is not only spatial but psychic, a retreat into self-reflection and literary production. The story she writes becomes both a record and a rejection of the life her son seems to be choosing. In this way, motherhood is not merely a background theme but a structuring force in Yalda’s diasporic consciousness.

Another powerful metaphor that Molavi employs is the figure of the jinn or hamzad, a spirit believed in Iranian folklore to be born at the same time as each human, sharing their fate and dying at the same moment. Yalda’s jinn appears unpredictably, reminding her of past traumas, unfinished grief, and unresolved relationships. The jinn does not comfort; she unsettles. She represents what Homi Bhabha terms the unhomely, the moment when the private becomes public and the familiar becomes estranged. The jinn is Yalda’s foreignness turned inward, the residue of a homeland that continues to haunt her in the interstices of Canadian life. Like the shadow man, the jinn cannot be assimilated. But unlike him, she is not external. She is a mirror, a doubling, a sign that exile is never complete because the past is not only behind but within.

The presence of the jinn—alongside Yalda’s memories of matals, old Iranian songs, and architectural elements such as the “panj-dari”—constructs a memory repertoire that is affective rather than archival. These memories are not presented as fixed cultural artifacts but as mobile, contingent, and deeply personal. In writing her story in thirty days, Yalda does not seek to explain Iran to a Western audience or to justify her place in Canada. Rather, she performs what Avtar Brah calls a “diasporisation of home,” a process of making home in movement, across linguistic, spatial, and temporal boundaries. This diasporization is marked by moments of recognition across other diasporas as well. Yalda reflects on her ESL student Asuntha, whose own traumatic migration story ends in psychic collapse. The failure of Asuntha to narrate her pain in a language understood by others serves as a haunting counterpoint to Yalda’s own attempt to woodle her life into story.

What remains is the act of narration itself, the insistence that even in exile, one can write, remember, and remake.

In the final scenes of the novel, Yalda leaves her story behind and returns to Toronto. As she departs, she sees a vision of thirty birds circling an altar, a symbolic convergence of the Simorgh myth and her own narrative journey. She hears a voice saying, “and it was not a dream,” a line that affirms the reality of what she has experienced, written, and imagined. This conclusion does not offer resolution. We do not know what the puppeteer will do with her story. We do not know if it will be performed or forgotten, altered or honored. What remains is the act of narration itself, the insistence that even in exile, even in the temporary shelter of someone else’s apartment, one can write, remember, and remake.

Thirty Shadow Birds resists easy classifications. It is not a refugee narrative, a nostalgia piece, or a testimonial designed for Western consumption. It is a novel that insists on complexity, on the ambivalence of belonging, and on the unfinished work of cultural memory. Through Yalda’s voice, Fereshteh Molavi reframes the act of storytelling as both a demand and a gift, a form of agency and a vulnerability. In so doing, she reimagines the Iranian diaspora not as a fractured population forever looking back but as a living collectivity in the making, scattered like birds but bound by the act of telling.

George Brown College

Works Cited

Bhabha, Homi K. The Location of Culture. Routledge, 1994.

Brah, Avtar. Cartographies of Diaspora: Contesting Identities. Routledge, 1996.

Dabashi, Hamid. Iran: The Rebirth of a Nation. Palgrave, 2016.

Milani, Farzaneh. Words Not Swords: Iranian Women Writers and the Freedom of Movement. Syracuse University Press, 2011.

Molavi, Fereshteh. Thirty Shadow Birds. Inanna, 2019.