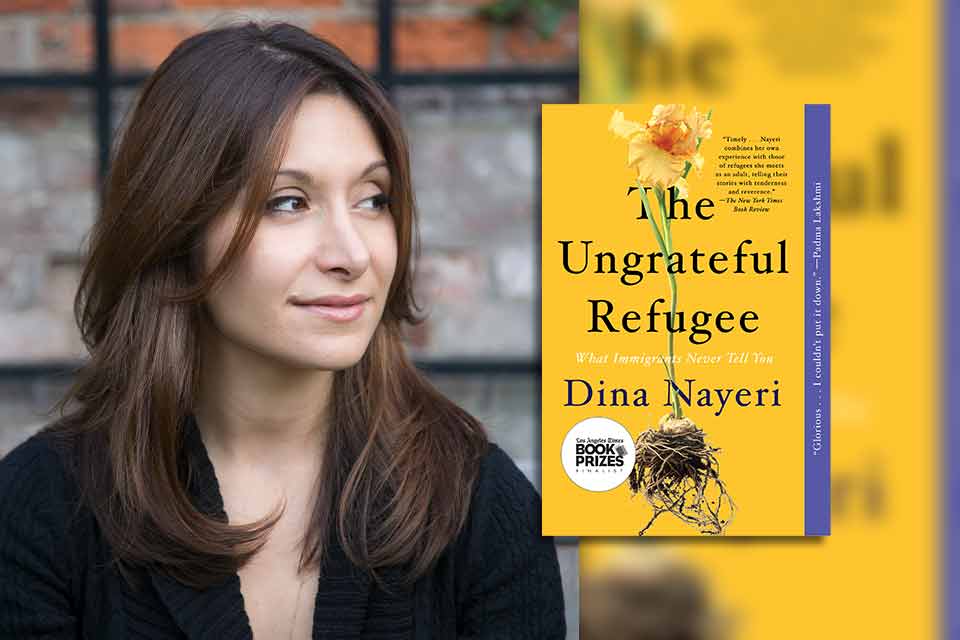

No Safe Place to Say Thank You: Ambivalence and Belonging in Dina Nayeri’s The Ungrateful Refugee

When migrants must perform gratitude to be believed, what happens to their truth? Dina Nayeri’s memoir disrupts the tidy refugee story, turning contradiction into resistance and the in-between into a place from which to speak.

When Waad al-Kateab, the Syrian filmmaker behind For Sama, walked the red carpet at the Oscars in 2019, her feet carried not only her body but the rubble of Aleppo. In interviews, she confessed a persistent longing to return to Syria, despite the devastation, despite the danger. Her longing was not naïve; it was carved into her like a phantom limb. The paradox of this desire—to return to a place that has exiled or endangered you—is neither masochistic nor heroic. It is one of the many impossible contradictions that exile imposes. For some, like al-Kateab, the exile remains a temporary rift.

I think of Dina Nayeri here, not because her life mirrors al-Kateab’s, but because she opens The Ungrateful Refugee (2019) by asking: What is the price of being saved? Who gets to narrate rescue, and on whose terms? Her memoir, or rather her hybrid narrative of memory, reportage, and reflection, does not chronicle trauma for redemption. Instead, it questions the moral architecture of asylum itself: its economies of gratitude, its spatial sorting of bodies, its demand that the refugee become a compliant beneficiary.

This essay explores The Ungrateful Refugee through three critical lenses: ambivalence as a mode of survival and storytelling; the politics of gratitude imposed on displaced subjects; and the spatial metaphors that encode the migrant’s in-betweenness. Rather than seek to resolve these tensions, Nayeri inhabits them, narrating a life in motion as both protest and poetics. Her refusal to offer the consolations of closure is a form of ethical resistance itself.

Ambivalence and the In-Between as Place: Narrative as Enunciation

Ambivalence is often dismissed as weakness, but for the migrant, it is an epistemology—a way of knowing the world in contradiction. In The Ungrateful Refugee, Nayeri does not organize her narrative by chronology but by recurrence. She returns obsessively to certain moments: the night in the Iranian desert where she fled with her mother and brother, the refugee camp in Italy, her school years in Oklahoma, and, most sharply, the rooms where her family was asked to “prove” their truth.

These repetitions are not redundancies. They mimic the migrant’s memory, which is fragmented, recursive, always interrupting the present. Ambivalence appears here not just as psychological residue but as structural resistance to the expectations of refugee narratives. Where the reader might expect triumph, Nayeri offers discomfort. Where the system demands gratitude, she poses grief.

Ambivalence appears here not just as psychological residue but as structural resistance to the expectations of refugee narratives.

Homi Bhabha’s theory of ambivalence in The Location of Culture (1994) helps frame this mode. For Bhabha, ambivalence destabilizes power structures because it reveals the cracks in colonial authority. In migrant literature, it functions similarly: exposing how asylum regimes want a singular, grateful subject but produce instead a plural, wounded self. Consider the moment when Nayeri recounts being told, as a child, that she should smile more and speak less Farsi, for example. This instruction is not about etiquette but about erasure. To smile, here, is to perform integration; to silence Farsi is to abandon history. Yet her memory holds both the smile and the language. The narrative refuses to choose. It survives by contradiction.

From the very first lines, we are confronted by a story that is not aimed to fit. And this, perhaps, is her most powerful gesture. Throughout The Ungrateful Refugee, Nayeri asks a question that cuts deep into the politics of asylum storytelling: What makes a “good” refugee story? In camps and courtrooms, a good story is one that is linear, coherent, and, above all, useful for the listener. It is a narrative trimmed of contradiction, cleaned of context, and presented in the syntax of victimhood. But Nayeri resists this—she offers instead what she calls the “unfit narrative,” the story that strays, that doesn’t match the file, the form, the policy.

Her narrative is hybrid—memoir, fiction, testimony, social commentary—and this hybridity becomes a form of enunciation. It speaks from the in-between. It is, in itself, a place. A place made of contradiction, memory, rupture, silence. The “non-place,” as she calls it, is not just a spatial void—“a place without a state that is responsible for you” (12)—but a narrative zone as well. What happens when no state, no voice, no system claims you? You build your voice in exile, as a “body out of place” (Ahmed). Nayeri endures exactly that. A body that cannot be naturalized into the myths of origin or the fantasies of arrival. The migrant body, in Ahmed’s framing, is an affective dissonance. It makes the native uncomfortable. It reminds the host of what must be erased to keep the homeland clean.

The migrant body makes the native uncomfortable. It reminds the host of what must be erased to keep the homeland clean.

The asylum process, then, becomes a performance—a ritual in which the refugee must be reshaped, remade in the image of the native. You must become recognizable. The right kind of trauma. The right amount of passivity. The right expressions of gratitude: “[as] recipients of magnanimity,” Nayeri writes, with bitter clarity (16). It’s a sharp phrase. It cuts through the benevolence that masks control. The refugee must say thank you in the correct accent, wear it on their face, in their résumé. What Nayeri does is refuse that performance. She asks, “When they do internalize the obligation to make room, they do so grudgingly, or with arguments about the supplication and usefulness of immigrants” (207). This refusal is not just rhetorical. It is structural. Her book doesn't “build” like a novel. It unfolds, spirals, returns. It doubts. And this form mirrors the dislocation she describes. A linear story would betray the life it claims to tell.

Academic works from Nando Sigona (2014) and Liisa Malkki (1996) have also critiqued the way refugee narratives are institutionally constrained, but they emphasize different dynamics. Sigona draws attention to the “one-dimensional representation” of the refugee as feminized, infantilized, and fixed in pure victimhood. This portrayal, he argues, expects the refugee to remain passive in order to be helped. In The Ungrateful Refugee, Nayeri resists this image by portraying herself and others not as docile recipients of aid but as complex individuals grappling with grief, memory, and agency. When compelled to answer gratefully for the chance of living in America, “You came for a better life,” her reply contains her resistance to gratitude and breaks with the expected narrative of submission: “[In Iran] I had a tree inside my house,” portraying the refugee not as a silent subject but as someone with autonomy—even anger (15).

Malkki, on the other hand, highlights how the refugee is often stripped of political and historical context. Rendered as a “universal humanitarian subject,” (378) the refugee is depoliticized, treated as a passive object of charity rather than a participant in a broader geopolitical story. Nayeri challenges this through her insistence on specific, grounded histories. Her account of fleeing Iran is filled with references to persecution, fear, and the decisions her family had to make within a volatile political climate. She does not allow the reader—or the asylum system—to ignore the intricate, lived context behind her migration.

Nayeri’s writing opens a space for those of us who also feel unfit. She does not give us the comfort of redemption.

Together, these critiques help frame Nayeri’s memoir as an active intervention in refugee discourse. Where policy and media often demand simplicity, passivity, and abstraction, she offers complexity, defiance, and historical rootedness. Nayeri’s writing does not attempt to resolve this, by the way. It lingers. It holds the contradictions. And in doing so, it opens a space for those of us who also feel unfit. She does not give us the comfort of redemption. But she gives us something rarer: the right to remain complex.

The Politics of Gratitude

“It’s not enough to be a refugee. One must also be a grateful one,” writes Nayeri. This deceptively simple sentence cuts to the heart of liberal humanitarianism: its reliance on a silent contract of emotional debt. The refugee must not only endure displacement, loss, and scrutiny but must also perform appreciation. Gratefulness becomes currency, traded for safety, for belonging, for reduced suspicion.

The politics of gratitude rests on an uneven moral exchange (Nguyen, 2012). Nguyen portrays how freedom, as offered to the refugee, is not a gift but a demand. One is given asylum in exchange for silence, loyalty, and applause. Nayeri resists this contract. She narrates her life not to prove worthiness but to question why worth must be proven at all by recounting how social workers and volunteers, despite good intentions, imposed a pedagogy of gratitude: lessons on how to behave, how to dress, how to respond to kindness. Gratitude here is not relational but disciplinary. It shapes the migrant body into a recognizably humble figure, an object of Western benevolence.

Her younger brother, Nayeri recalls, refused to participate. He grew sullen, then angry, then silent. His refusal was misread as ingratitude, defiance. But perhaps it was also resistance. To refuse to say thank you can be a way of preserving dignity, a way of saying: I was a person before you saved me. This refusal echoes in Nayeri’s prose. Her narrative voice does not beg for empathy. It exposes its mechanisms. It challenges the reader to reconsider whether empathy itself can be a tool of domination when it demands emotional servitude from the already displaced.

Spatial Representations and Belonging to the In-betweens

Nayeri's memoir is rich with the cartography of exile. It is a literature of corridors, border offices, waiting rooms, and thresholds—spaces that do not signify arrival but the deferral of arrival. These in-between spaces are not simply backdrops but active terrains of tension, surveillance, and uncertainty.

Drawing on Doreen Massey’s notion of place as a meeting of trajectories rather than fixed identity, one can view Nayeri’s experience as spatially fractured (2005). The refugee camp in Italy, for example, is not just a site of temporary residence. It is a space where time stagnates, where subjecthood is suspended. The camp is not a place where one lives, but where one waits—to be processed, to be believed, to be reclassified from disposable to legitimate.

Michel de Certeau’s theory of space (1984) as practiced place also resonates here. In her descriptions of shared kitchens, cots, or immigration offices, Nayeri shows how even institutional or impersonal spaces become affectively charged. The asylum office is both stage and battlefield; the family kitchen, a liminal zone between cultures. More than just physical locations, these spaces hold the sediment of emotional labor. Spatial dislocation becomes psychic dislocation. A child sleeping on a thin mattress in an Italian camp is also already inhabiting future tensions: of translation, of code-switching, of permanent unbelonging.

In this sense, Nayeri’s memoir becomes a map of estrangement—not a movement from point A to B but a circular drift across emotional geographies, where no point of anchoring lasts. Her narrative reclaims these spaces not to offer resolution but to show their lasting inscription on the migrant soul.

Nayeri’s memoir becomes a map of estrangement—not a movement from point A to B but a circular drift across emotional geographies.

What does it mean to belong without being claimed? For many migrants, belonging is not a place but a practice: a temporary stitching together of memory, desire, and recognition. In Nayeri’s case, belonging is always unstable. Iran is a site of origin but not return. Europe is a site of transition but not home. America is where she was schooled but never fully accepted. She writes, moves, teaches, and raises a child, yet there is no singular center from which her identity emanates.

In Reflections on Exile, Edward Said wrote that “exile is strangely compelling to think about but terrible to experience” (173). Nayeri captures this paradox in language that is at once precise and porous. Her griefs do not resolve; they expand. Her gratitude does not arrive; it refracts. And in this refusal to offer narrative resolution, she grants herself a different kind of belonging: one rooted in the right to complexity.

Literature, in this context, becomes not a mirror but a container. It does not reflect a stable identity; it holds an unstable one with care. In Born Translated (2015), Rebecca Walkowitz argues that contemporary world literature often emerges already displaced, already in transit. Nayeri’s memoir fits this frame. It is a book that crosses genres and borders, defying the neat categories that publishing and politics often demand.

In the end, perhaps gratitude is the wrong question. Perhaps what Nayeri demands is not recognition of her thankfulness but acknowledgment of her full humanity: contradictory, wounded, unfinished. The migrant, in her telling, is not a solved equation but an open one. And maybe that is enough.

Universidad Industrial de Santander

Works Cited

Ahmed, S. The Cultural Politics of Emotion (Routledge, 2004).

Bhabha, H. K. The Location of Culture (Routledge, 1994).

de Certeau, M. The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven Rendall (University of California Press, 1984).

Leurs, K., et al. “The Politics and Poetics of Migrant Narratives.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 23, no. 5 (2020): 679–97.

Malkki, L. H. “Speechless Emissaries: Refugees, Humanitarianism, and Dehistoricization.” Cultural Anthropology 11, no. 3 (1996): 377–404.

Massey, D. For Space (SAGE, 2005).

Nayeri, D. The Ungrateful Refugee: What Immigrants Never Tell You (Canongate Books, 2019).

Nguyen, M. T. The Gift of Freedom: War, Debt, and Other Refugee Passages (Duke University Press, 2012).

Said, E. W. Reflections on Exile and Other Essays (Harvard University Press, 2000).

Sigona, N. “The Politics of Refugee Voices: Representations, Narratives, and Memories.” In The Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies, edited by Fiddian-Qasmiyeh et al., 369–82 (Oxford University Press, 2014).

Walkowitz, R. L. Born Translated: The Contemporary Novel in an Age of World Literature (Columbia University Press, 2015).