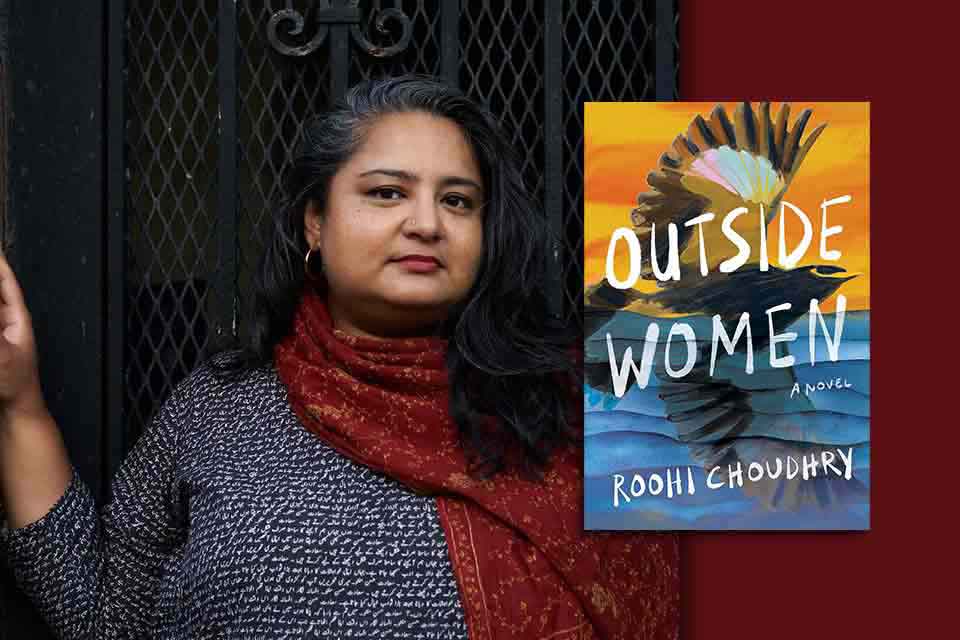

“When You Are Outside, You Can Be That Wild Thing”: A Conversation with Roohi Choudhry

Roohi Choudhry’s debut novel, Outside Women, braids the stories of two women: Hajra, a Pakistani scholar in the US in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and Sita, an indentured Indian servant in nineteenth-century South Africa. Becoming outsiders as their places of origin undergo social and political changes forces characters to migrate. Choudhry’s lyrical storytelling immerses readers in the characters’ struggles in (post)colonial, transnational spaces, and her multifaceted narrative renders with suspense their efforts to redefine their womanhood outside of existing institutions.

Born in Pakistan and raised in South Africa, Choudhry lives in New York and has worked as a researcher in criminal justice reform and public health, written for the United Nations, and held writing workshops for interfaith, educational, and community organizations. Her focus on social justice and empowerment is reflected in the epic journeys of her layered characters across three continents. Selected from highly competitive annual open submissions, Outside Women was published as part of the University Press of Kentucky’s New Poetry & Prose Series.

I had the opportunity to speak with Choudhry about her inspirations and her characters’ journeys.

Serkan Gӧrkemli: Can you talk about how you came up with the title Outside Women?

Roohi Choudhry: At some point in the revisions, this idea of outside women as women who have been shut out of societal expectations, norms, and institutions, and what happens to them on the outside, came to the fore. I was interested in that idea from a feminist perspective. My agent and I also spoke about what was most thematically resonant, and she agreed that this is a title which could further a conversation. So, when it comes to sharing the book with the world, it’s also thinking about what can provoke conversation.

Gӧrkemli: A ghostly presence that resonated with me is the tree witch, who is the original outside woman, an archetypical feminist figure in your book. Could you tell me about her origin story?

Choudhry: Folktales have always been a fascination. My grandfather told me one. A young woman goes into the woods and comes home late, drenched in the rain and dripping red dye from her scarf. Her brother kills her because of the ruined scarf. As an adult, I see it not just as a menstrual taboo but also, of course, a sexual one, the implication being that she strayed, and that is what has tainted not only her but also everyone, so she must be killed.

I think it was on my mind that these are the kinds of tales girls are being told, so I included the story of the tree witch as something that Sita hears as a child—I felt very drawn to the tree imagery as something to do with the land, a form of connection in a way that is beyond our usual realist experience. I wanted it to be a particular tree, a so-called invasive species in South Africa, from India. We used to have one in our backyard. And I thought maybe I’ll rewrite this folktale to suit my purposes. It has some of those elements of the girl who’s gone outside and strayed, but instead of becoming a victim, she would become a tree witch, become one with the tree. That made it a more interesting folktale for me rather than just a cautionary tale.

Gӧrkemli: I love that you took a disempowering folktale and made it into an empowering story. What are some other experiences that might’ve inspired the book?

Choudhry: Being an outsider is a huge inspiration to me, as someone who has migrated so many times. It started when my family first moved to Durban, South Africa, when I was thirteen, toward the end of apartheid. A huge percentage of Durban’s population is descended from indentured laborers. So, that’s the start of my obsession with this history. For me, migration was a nonlinear experience, somewhat chaotic and in many directions, and I was really interested in these different kinds of migrations and how those different diasporas interconnect and crisscross across time. As a woman who later migrated to the US without my family, I was having some of the echoes of those experiences, like a sense of solidarity to be had through that history, which could be a form of community.

Gӧrkemli: Your biography sheds light on the braided structure of the book, with three major settings—Peshawar, Pakistan; Durban, South Africa; and New York, USA—and two main characters whose stories are intertwined: Hajra’s past and present and Sita’s journey. Can you talk about how you structured the book?

Choudhry: The structure was really hard, so thank you for appreciating it. I kind of struggled with a lot of different kinds of structure. A couple of things helped: I showed it to our mutual friend Nawaaz Ahmed, and he replied, there are three stories here. Around the same time, when you and I were both at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, I attended a craft lecture with Ingrid Rojas Contreras, and she had this really great way of thinking about structure as more creative imagery than a rational structure, so I thought of this idea of the braid or the plait—it’s so iconic among South Asian women to have their hair in a plait. When you make a plait, there are three strands, and then I was like, okay, this needs to be three stories.

Gӧrkemli: One of those three stories, Hajra’s past in Pakistan, includes one of the tragedies of the book: the growing distance between Hajra and her brother Ali that begins with the political changes in Pakistan. Could you talk about that a little bit?

Choudhry: Before Hajra even existed in my mind, I wrote this short story called “This Is What We Could Have Been” around 2010. I felt most proud of it because it helped me channel a feeling I was having that was so hard to name, of having really lost my country to this kind of rising religiosity and political unrest that made it feel like a foreign land. I wrote that story after I had a dream of grief that involved these children whose father didn’t recognize them. They were like that sense of the country, not the country as some kind of nationalistic idea or a theoretical idea, but really like a deep sense of familiar connection, that sense of our most intimate relationship with land and place that is lost. So, that way of thinking about how to process and how to write fiction about this feeling was something I channeled into this novel. I wanted to use this sibling relationship as a way to reflect this very deep loss that feels completely destabilizing.

Gӧrkemli: In chapter 11, Hajra witnesses an acid attack, and it scares her into withdrawal from activism against rising religious radicalism in Pakistan. Her line, “Once outside your home, the space you occupy is rented, it belongs to them,” really encapsulates the feminist critique of the book, right?

Choudhry: Thank you for noticing that line, because I felt it deeply myself when I wrote it. The idea of women in public space, stepping outside home—whether that means literally outside in your own neighborhood or migrating across the ocean—is such a big part of this book and of why it’s called Outside Women. I wanted to explore in the book the theft of this public space from us, which is a huge violation—that so much of public space is not open to us, that you’re being told to dress in a certain way, or that we walk home with our keys in our fist.

I wanted to explore in the book the theft of this public space from women, which is a huge violation.

That is how being a whole person in a public space is taken away, and to me, that is one of the many hard things about living in a patriarchal world. It’s an underlying violation throughout all the different stories in the book. That was a big part of what I wanted to write about. I was really inspired by this book called Women Who Run with the Wolves, by Clarissa Pinkola Estés, about women reclaiming a sense of wildness or a wild self. When you are outside, you can be that wild thing, you know? You can claim some aspect of that self which is not bound by these norms, and then you can explore what it really means to be outside, reclaiming power to be something different, something new.

Gӧrkemli: As it happens with your characters, changing politics in different national contexts could aggravate that existing injustice of women not being free outside, right?

Choudhry: I’ve seen that happen in my own life over time as someone in my forties now. In many of the places I’m talking about, it has gotten much worse. My mom tells me about what she could do freely, like going to the movies, in Pakistan, but I couldn’t imagine doing that when I was living there as a young person in college because you would’ve been harassed too much. Now, apparently, if you have enough money, you can go to the movies because there are these fancy places. So, it’s not linear; policies and movements can further confine women.

It’s not linear; policies and movements can further confine women.

Gӧrkemli: Sita’s photo serves as a catalyst for Hajra’s going to South Africa and experiencing an awakening. Can you elaborate on Sita’s importance for Hajra?

Choudhry: Hajra is finding an ancestor for herself. The sense of recognition she has with that photo is really about the way in which you recognize your ancestor. It’s a bit of a fantasy in some ways.

Gӧrkemli: Perhaps Sita is also a feminist foremother for Hajra because Hajra has an ethical choice to make, so, I think, Sita becomes a source from which Hajra draws power in facing what she’s asked to do.

Choudhry: Absolutely.

Gӧrkemli: The other aspect of Sita as a character is that she has an emerging queer consciousness. You let readers know about this, but the irony is that Hajra will never know because it’s not in the archives she visits when researching Sita’s past life in South Africa.

Choudhry: Yeah, there is a lot more in general; the archives are not the end of our experience of the past, and that’s something I wanted to thread through. Hajra is getting a glimpse of the sense of ancestry with Sita in ways not fully possible to understand because the record cannot really contain that sense of connection. But she can still feel a sense of empowerment in the knowledge and deep connection that goes beyond the archive. A lot of queer people have that because, you know, queer people are erased from the records, from history. In some cases, they have excavated their histories and found their ancestors, but then there’s the loss of other stories that are still alive, like in our experiences and our memory.

Gӧrkemli: There are other ways in which I read your book queerly. For example, the dropping of Rakesh out of the book at the end also perhaps says something, but I might be reading into it. Anyway, please talk a bit more about queerness.

Choudhry: Everyone feels differently about these terms, but for me, queerness is another word for being outside of these institutions, the societal bounds, the expectations of gender. That’s how I understand queerness for myself and the way I wanted to write about it here. In terms of romantic relationships, in so many traditional narratives, women’s love and relationships are always in relation to men, so writing a book that is inherently about the connection between two women is queer, you know?

So, I wanted Hajra and Sita to have a sense of expansiveness of relationship, that there are ways for them to be connected even though they are not related and never meet. That in itself challenges those heteronormative ideas of how people are connected and how families are. I do kind of think in my mind that Hajra and Rakesh are together and happy somewhere, but I don’t think of that as the end, or the peak, of her story. It’s one of the many relationships, and I didn’t want that to define the arc of her story.

Gӧrkemli: When I finished reading your book, my first reaction was, What’s going to happen next? But since then, I feel the book ends in the right place. What are your thoughts about the ending?

One of the points of the book is that justice is not to be found in existing institutions if you are systematically excluded.

Choudhry: One of the points of the book is that justice is not to be found in existing institutions if you are systematically excluded. That’s basically what has happened throughout the colonial project in so many ways and continues to happen in the neocolonial project. This is about outside women, so I felt that it was important to stop at just that point, where these women are coming to those institutions, and basically, they’re going to turn away and take that power outside of them with others.

So, to me, that’s the resolution: they’re both able to find a way to do that. That is a huge step and a huge risk. We don’t know, for either one, whether she’s going to be alive, you know? There are different question marks you might have at the end of a book, but I was aware that in this book—is she going to be alive tomorrow? It could go in different directions, but we can acknowledge that they’ve both become their truest, wildest, boldest selves in that moment, and they’re able to find their way to that question of what is possible outside of existing institutions.

Gӧrkemli: You write beautifully about nature, so I would love for you to reflect on two moments in nature: when Sita is on the river with her family, and when Rakesh and Hajra go to a nature preserve in Durban.

Choudhry: A lot of writers of color have talked about wanting to write about flowers but instead writing about pain, you know, like “the pain of our people.” I had felt that for a long time, too, that I wanted to use writer’s tools to portray beautiful parts of our world, but I felt drawn to what feels so much more urgent, and that in itself is a frustration. But then, at some point, I was like, these things are connected, and having the natural world is a way of emphasizing that there is this wide world on the outside which is supposed to be our home, and yet, it is not. Lots of people have spoken much more directly about women and people of color in this country being shut out of the natural world, in terms of safety and in terms of all sorts of things. So, a way to reclaim some of that space was to write about it and situate the characters in those places.