Tyrus Wong’s Visionary Bicultural Aesthetic: A Conversation with Karen Fang

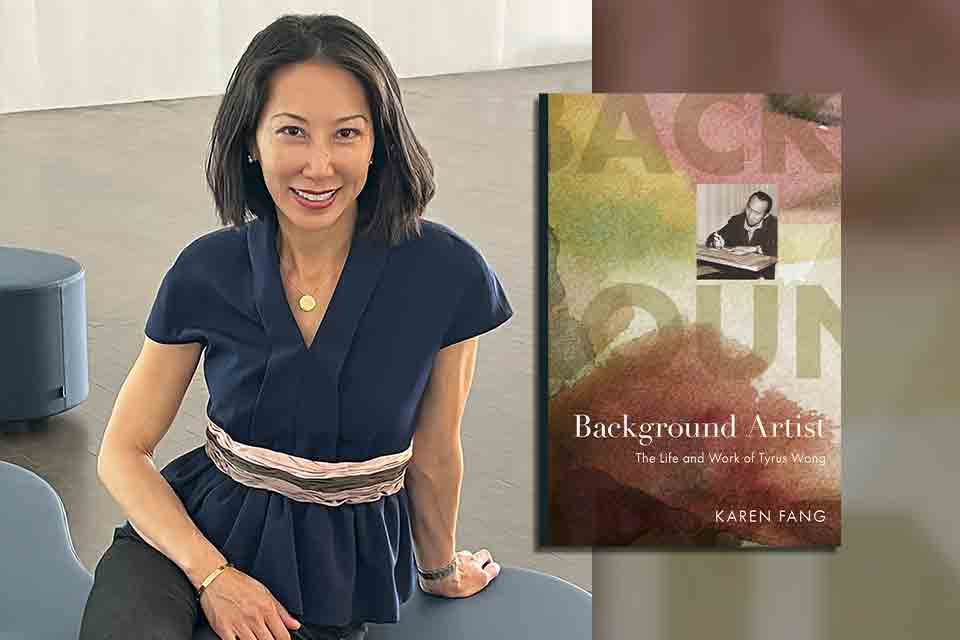

Karen Fang is professor of English at the University of Houston and author of the new book Background Artist: The Life and World of Tyrus Wong (Rutgers University Press, 2025), which is a biography of the Chinese immigrant artist, centenarian, and Disney legend who helped make Bambi. Background Artist recently received an honorable mention for the Chinese American Librarians Association’s Best Book Award in the adult nonfiction category. A film scholar and founder of the Media and Moving Image Initiative at the University of Houston, Fang also wrote Arresting Cinema: Surveillance in Hong Kong Film (Stanford University Press, 2017). I recently interviewed her via email about her new book, the golden age of Hollywood, and where she finds inspiration for her books.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: I have so many questions but will begin with Tyrus Wong because your most recent book is a biography of his incredible life. Can you talk a little about when you first heard of him and how you decided to write his biography?

Karen Fang: Like many people, I was captivated by the extensive coverage of Tyrus when he passed in 2016 at the remarkable age of 106. A documentary about him had just come out the year before, and his passing in late 2016 (just after the first Trump election) came at a time of heightened anti-Asian, anti-immigrant rhetoric. I was fascinated by this Chinese immigrant who couldn’t even become a citizen at the time he helped make Bambi. Once I learned more about his career, which included fine art, nearly three decades at Warner Bros., and fame as a best-selling greeting-card artist, I knew we needed a full-length book about this remarkable man.

I was fascinated by this Chinese immigrant who couldn’t even become a citizen at the time he helped make Bambi.

Blumberg-Kason: Tyrus arrived in the US from southern China at a time when the US government banned Asian and other ethnic Asian immigrants from coming to America. Like many Chinese immigrants, Tyrus became a “paper son” in 1920, taking on an identity that was not his own. Paper sons had become very common after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, when much of the immigration documentation was lost. When you were writing Background Artist, did you ever think Tyrus’s story would seem so timely given the state of today’s US immigration policies?

Fang: Yes, already at the time of Tyrus’s death in 2016, the issue of immigration and America’s ambivalence regarding ethnic Chinese and Asian citizens was already in high relief, but even so it was shocking to see this long, sad history continue. In 2018, when I was just starting research on Tyrus, US border policy resumed a family-separation practice used more than a century earlier, when Tyus arrived in America as a ten-year-old boy. Much of my research and writing for Background Artist occurred during the pandemic, when anti-Asian feeling was widespread. Today, federal funding cuts and policy changes are drastically impacting both the number of immigrants who can enter the US and the capacity of schools and universities to educate Americans about the important role immigration has always played in our national history.

I find all this disheartening, but I am sustained by the incredible example of Tyrus himself. Despite enduring terrible circumstances, he left his mark throughout American visual heritage. Tyrus’s ability to transcend hardship through creativity is endlessly inspiring.

Tyrus’s ability to transcend hardship through creativity is endlessly inspiring.

Blumberg-Kason: I loved reading about Tyrus not only because of his artistic accomplishments but also because his story is so American. Tyrus’s work may be most visible in Bambi, but he was also very involved in other forms of commercial art and in the New Deal, namely the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project. Can you talk a little about how he came to work in the Federal Art Project and what you consider to be his most successful projects at that time?

Fang: The Federal Art Project (FAP) was the fine arts wing of President Roosevelt’s Depression-era economic revitalization program. The FAP enriched American culture by employing needy artists to create fine art works for the benefit of American citizens, such as murals in schools and government buildings, or paintings and fine art prints that could be loaned to local communities. When Tyrus joined the FAP in 1936, he had already developed a reputation for his Chinese-style brushwork. At an FAP exhibit in a public library, one of Tyrus’s paintings won a vote as the community’s favorite piece!

So many paintings and prints were produced during the FAP that although many were lost over the decades, it is not uncommon for works to suddenly surface. I recently heard from a museum in Bellingham, Washington, a university town not far from the Canadian border, which has a Tyrus FAP print in their collection. For me this was particularly meaningful, as I was born in Bellingham, where my Taiwanese immigrant parents first settled. But it is also typical of the FAP legacy, which brought fine art to towns throughout the nation. It’s also particularly indicative of the diversity of artists in the western states, whose position on the Pacific coast meant that the FAP included a number of ethnic Asian artists.

Blumberg-Kason: As you mentioned earlier, Tyrus lived to the distinguished age of 106! When we were on a biographers’ panel together last year, we spoke about contacting and befriending the families of our biography subjects. This is perhaps the scariest and most rewarding part of writing biography. What were your biggest surprises when you reached out to Tyrus’s family? And do you think it’s possible to write a biography without contacting the family?

Fang: Tyrus’s life is so inspiring and he was himself such a likable guy that I knew his biography would be free of the problems facing other writers, who might need to share content or characterizations to which the family objects. Still, like many biographers, I encountered instances when documentation differed from people’s memories. Also, because art is fundamentally subjective, there were inevitable moments when my description or interpretation of Tyrus’s work varied from that of his family and close associates. At these moments I had to rely on my position as a scholar whose commitment is first and foremost to the research.

There are countless historical subjects and figures that might require a biographer to proceed without family cooperation, but Tyrus was not one of them, fortunately. Indeed, one of the great pleasures of researching his life and career was the incredible community of creatives to which he belonged and whom he inspired. Tyrus passed before I could meet him, but I met many artists, animators, writers, and filmmakers whose current practice helped me understand his personality and legacy.

Blumberg-Kason: This may be an impossible question to answer, but if you could pick three pieces of Tyrus’s work that you love the most, which would they be?

Fang: Bambi is so iconic that it may forever be the thing for which he is most famed, but I think his fine art paintings Self Portrait (ca. 1932) and Chinese Jesus (1936) will soon become parts of the canon of American art history. Made around the time he graduated from art school, Tyrus’s soft watercolor Self Portrait portrays himself with a bamboo paintbrush in hand. The work resembles traditional Chinese painting—but also shows Tyrus wearing suspenders and modern Western pants and shirt, exemplifying the fusion of Eastern and Western aesthetics for which the artist was already gaining critical attention.

Similarly, the monumental religious painting now known as Chinese Jesus illustrates Tyrus’s visionary bicultural aesthetic on an even grander scale. The vividly hued oil painting, which is over six feet tall, was commissioned by a Chinese American church and embodies an artist and congregation equally comfortable in both Eastern and Western culture. The full-length Christ portrait shows a begowned Jesus with halo, red hair, and almond eyes. The deity floats in the heavens and holds his hands out in supplication, but the stylized cloud at his feet and the drape of his hand are more reminiscent of Buddha than traditional Christian imagery. A painting of this size and subject would be a major accomplishment for any artist, but Chinese Jesus is especially important for its audacious fusion of Western and Chinese culture. Decades before “Black Santa” and current questions about “What did Jesus really look like?” Tyrus made this unforgettable masterpiece of bicultural vision and style.

Chinese Jesus is especially important for its audacious fusion of Western and Chinese culture.

Blumberg-Kason: I first became acquainted with your work when I reviewed your 2017 book, Arresting Cinema: Surveillance in Hong Kong Film. I spent most of the 1990s in Hong Kong and felt like you were speaking to me in your pages! I had never thought about surveillance in film and especially not in Hong Kong movies, which I had assumed were outlets of entertainment—and fabulous ones at that—for a city that never slowed down. Can you discuss how you first became interested in that topic?

Fang: My first visit to Hong Kong was also in the mid-1990s, and I was struck by the ubiquity of surveillance practices throughout the city. At that time, London was often said to be the world’s “most surveilled city” due to the rapid spread of CCTV monitoring, but Hong Kong seemed to be just as rife with CCTV cameras as well as private security at even modest residences and businesses, and it was common for anyone in the city to be asked to produce identification at any time. With Hong Kong’s status as a British colony then about to revert to Chinese communist control, what were the economic, political, cultural, and historical reasons for this unparalleled surveillance culture?

Fang: My first visit to Hong Kong was also in the mid-1990s, and I was struck by the ubiquity of surveillance practices throughout the city. At that time, London was often said to be the world’s “most surveilled city” due to the rapid spread of CCTV monitoring, but Hong Kong seemed to be just as rife with CCTV cameras as well as private security at even modest residences and businesses, and it was common for anyone in the city to be asked to produce identification at any time. With Hong Kong’s status as a British colony then about to revert to Chinese communist control, what were the economic, political, cultural, and historical reasons for this unparalleled surveillance culture?

Cinema is a great way to explore surveillance, both as window onto society and because surveillance is a key theme in some of the most important films of Western culture. Think of Hitchcock’s Rear Window, Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, Chaplin’s Modern Times, and Coppola’s The Conversation. Hong Kong film has long been one of the world’s great cinemas, and its frequent depictions of surveillance are both a glimpse into the territory’s unique surveillance culture and a symptom of the film industry’s global aspirations. Even today, as Hong Kong and Hong Kong cinema both look so different from the time you and I remember, I am fascinated by film’s capacity to express cultural identity and explore the possibilities of different futures.

Blumberg-Kason: I just looked back at our emails and see that we started corresponding five years after Arresting Cinema came out. You reached out to see if I had come across the Hollywood costume designer Dorothy Jeakins in my research of the Shanghai and Hollywood salon host Bernardine Szold Fritz. You write about Dorothy in Background Artist because she went to art school with Tyrus. And now you’re working on a biography of Dorothy. I think biographers have these “eureka!” moments when we can’t stop thinking about someone and know it won’t end until we research and write their stories. Do you remember when you knew you had to write about Dorothy?

Fang: Three-time Oscar-winning costume designer Dorothy Jeakins is so well known in Hollywood film history that I already recognized her name when I started researching Tyrus. She won an Oscar for her very first work as costume designer, on Ingrid Bergman’s 1948 Joan of Arc, and also did the costumes for The Sound of Music. My eureka moment with Dorothy was when I started diving into her personal archive as part of my Tyrus research. While I already knew about her film work, I didn’t know she had managed to achieve all that as a single mom of two boys. Like her art school friend Tyrus, Dorothy is a story of creative success against formidable odds.

Blumberg-Kason: Finally, besides being a gripping and important American story, Background Artist is also a physically beautiful book. It’s a hardcover with one hundred black-and-white and color photos and images from Tyrus’s art and life. What advice do you have to aspiring biographers who hope to show their subjects in the most stunning light? Did you have any problems getting your publisher to include all these fabulous images?

Fang: It’s easy to find good illustrations when your biographical subject is an artist! With a prolific artist like Tyrus, the challenge was choosing which items to reproduce. In his greeting cards alone, there are over five hundred unique published designs! Art reproduction also involves complicated copyright, license, and intellectual property issues. We’re lucky today that improved printing technology makes high-quality illustration increasingly affordable, so in Background Artist we chose to use both in-line illustrations (matte images printed directly on the same page as the text) as well as a traditional insert of glossy plates. We did this because I wanted to show the continuity of Tyrus’s artistic vision, even as he moved back and forth between fine and commercial art. In a subtle but powerful way, I hope readers pick up on the versatility of this brilliant and unique artist.

Blumberg-Kason: Thank you again so much for chatting about your work. I cannot wait to read more from you about Dorothy Jeakins!

Editorial note: For more on Hong Kong, check out WLT’s 2018 city issue, plus Man-Fung Yip’s 2017 city profile.