A “Rootless Rhizome”: A Conversation with Mariana Sabino

Mariana Sabino’s debut short-story collection, The Verdigris Stories, transports readers to many different countries. This collection of loosely linked stories features characters searching for a wider sense of identity while navigating familiar and unfamiliar places. Their displacement means the stories often work outside previously established social and national boundaries, and the reader experiences discovery alongside the characters.

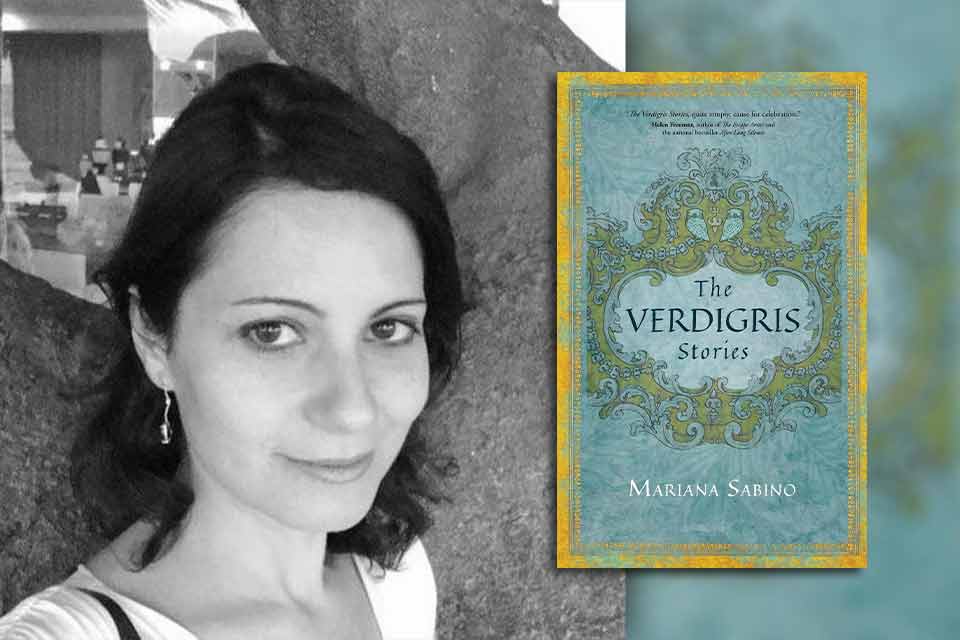

A dual citizen of Brazil and the US, Sabino has also lived in Europe for several years. Her perspective on various cultures imbues a layered, multidimensional texture to her characters, and her schooling in screenwriting is evident in her stories’ cinematic landscapes and settings. The Verdigris Stories was awarded the Independent Publishers of New England’s 2024 Gold Medal for literary fiction. Her work has also been shortlisted for the Granum Foundation Prize.

I had the chance to hear more about what Sabino set out to explore by writing stories based on the lives of expats and wanderers.

Geoff Graser: Your book’s title comes from the eponymous story in the collection, in which the female protagonist, Eva, originally from the Czech Republic, spends a significant time in her life in Brazil. What does that title mean to you, and how did you decide it was a good fit for the entire collection?

Mariana Sabino: The word verdigris speaks of impermanence and the slow but ever-changing reality of all things. It’s often a visible marker of the process of change on a solid surface—say, a copper sculpture, of which there are so many striking examples in the Czech Republic. It happens through oxidation. Air. It is a process that is both unstoppable and unpredictable, interacting as it does with other elements such as the salt from seawater. While I was writing the story, the name came to me after reading an article in the Paris Review about the enigmatic patina of verdigris, a shade that cannot be easily categorized, especially as its nuances are so particular to the object and where it is placed.

I thought verdigris was an apt metaphor for the story and, then, the entire collection—speaking as it does of themes of unpredictability, eluding categories, and longing and grasping at what is inherently ephemeral. Many of the characters in the collection, including Eva, do not clearly identify with one place or culture alone and struggle with a sense of belonging in conventional terms. Yet, at the same time, they cannot help but bring their backgrounds with them (their “solid” surface) while interacting with the new air they encounter, an air that invariably changes them. There’s also the counterpoint of resistance to change, which makes it even more difficult for characters.

Graser: Your stories are set in Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Greece, Brazil, Ireland, and beyond. How did these settings and cultures inspire the narratives?

Sabino: Simply put, these are the places that I can recollect whose grounded reality could more easily blend with imagination. I have also kept some writing of sensorial images from the places where I’ve been, which obviously helps when creating the setting and atmosphere of the story. That said, what the characters—or narrators—notice also reflects their lenses, illusions, and blind spots.

Graser: There’s a more whimsical story called “Not so Still Life” and one called “The Tabby of Azahar,” which is surreal. One story, “In Between,” is unique because it’s the only one set in the US. How did you decide on the order of the stories?

Sabino: The first three stories are closely linked, and a story follows another when they share the same setting or character. Some characters make cameo appearances throughout the book, offering another glimpse of where they might be at a given point. The more surrealistic stories, aside from departing from realism, also break from the immediate logic of a thematic unit of place or character, which may come as a jarring and hopefully refreshing turn if one is to read the book sequentially. One may think of it as a jump cut or absurdist progression.

Graser: You include various art forms in many of your stories—painting, music, film. Could you speak to a couple of instances of allusions to art and why you chose to include them?

Sabino: When I imagine a scene, certain songs, images, and paintings help round it out. Songs from the English band The Cure keep popping up in the collection, sometimes speaking for the characters. I suppose I can’t separate literature from all the other art forms since characters, like real people, are constantly influenced by what they see, hear, and sense.

Songs from the English band The Cure keep popping up in the collection, sometimes speaking for the characters.

When a character first arrives in Prague, she’s dazzled by her first encounter with Alphonse Mucha’s work, whereas another, more jaded character might speak of art-nouveau overkill. When an expat character begins to open up to the culture in Slovakia, the country in which she’s living as an English teacher, she’s listening to Marián Varga, an avant-garde Slovak composer. In Brazil, this happens for a new transplant when she begins to listen to Egberto Gismonti, signaling the crossroads to a more nuanced and deeper understanding of a place.

Graser: Many of your characters seem out of place in their surroundings, foreign in their “home” environment and even their language. How does this sense of foreignness relate to their dilemmas and search for something outside their given circumstances?

Sabino: Maybe it’s because I was an only child, or that I tend to be more of an outsider in group settings. I can usually spot those whose sense of belonging doesn’t come easily. As someone who emigrated to the US in my so-called formative years, transplanted into a new environment that I absorbed like a young plant, I still wound up missing out on references, customs, and cultural markers familiar to those whose growing-up experience in one place had been continual. This would become apparent upon my return to Brazil after so many years living in Europe. For that, when using the plant analogy, I identify as a rootless rhizome, as I believe many third-culture people might. I’ve also met many people whose perspectives and interests transcend their “givens,” people who might be described as natural voyagers, propelled by an inner compass to roam.

I identify as a rootless rhizome, as I believe many third-culture people might.

Graser: The collection explores themes related to dislocation, expatriate life, belonging to nowhere in particular, and trying to find your place in the world at large. How did these expat stories come about?

Sabino: Writing about characters whose experiences echoed or challenged my own observations intrigued me. I lived in Prague, for example, as an expat. As a student in Prague and then as an English teacher, the city kept pulling me in. Back then, renewing one’s visa was a matter of a train ride to a neighboring country for a reset. The expat circles allowed for the gathering of many perspectives related to both the draw and frustrations of living in a parallel reality to the locals. The expat experience, of course, differs from that of being an immigrant. The very semantics implies the former may be temporary and buoyed by some form of privilege. Many people live as expats throughout their lives as well, which can turn into a state of mind.

The expat experience, of course, differs from that of being an immigrant. The very semantics implies the former may be temporary and buoyed by some form of privilege.

Graser: How do you see the tension between the characters’ circumscribed world and their seeming expansiveness, their wish to explore a different way of life?

Sabino: A lot of it has to do with conventional ways of thinking, being, and living. Some characters tend to seek expansion without overtly confronting others. Often, this leads to long periods of stasis and loneliness. The tension is there all the same, as one can disturb others by merely being dissatisfied and unimpressed with the consolation prizes of society—status, camaraderie, acceptance—when they trample over individual callings. One of the major tensions is also that of ethnocentric thinking—between those who naturally cling to it and those who eschew it or find it too limiting. One way in which ethnocentrism can manifest is having someone claim this or that place is better or worse than another. Who is to say what is better for each person?

Graser: Why did you write this book in English rather than Portuguese? How does writing in English inform your approach? What’s the draw of exophony?

Sabino: Beyond childhood, most of my engagement with literature came by reading and writing in English, so writing prose, at least, feels more comfortable in English. It’s the language that also mediated my introduction to and discovery of international writers, from Milan Kundera to Arundhati Roy.

I also find that writing in English, especially now that I’m mostly living in Brazil, feels as though I were speaking to a friend, say, from Istanbul or Prague or India. Owing to my life experiences, speaking to someone through a common language that may be a second or third language but has been assimilated into one’s way of thinking and being seems . . . natural. Odd and natural.

When I delve into poetry or more experimental writing, though, I often write in Portuguese. I’m also reading more and more in Portuguese, so who knows? Maybe I’ll write more in Portuguese in the future.

Graser: You attended the renowned film school FAMU in Prague. How does visual storytelling influence your prose?

Sabino: I first studied acting and drama before delving into screenwriting. Before FAMU, I was finishing my bachelor’s at Charles University, completing what was left of my cinema studies minor. Going to FAMU further introduced me to avant-garde films and filmmakers who have since indelibly shaped my predilections. Admittedly, I often cannot help but think in scenes, which is usually how a story first enters my mind. Once it does, it becomes much easier to write.

February 2025