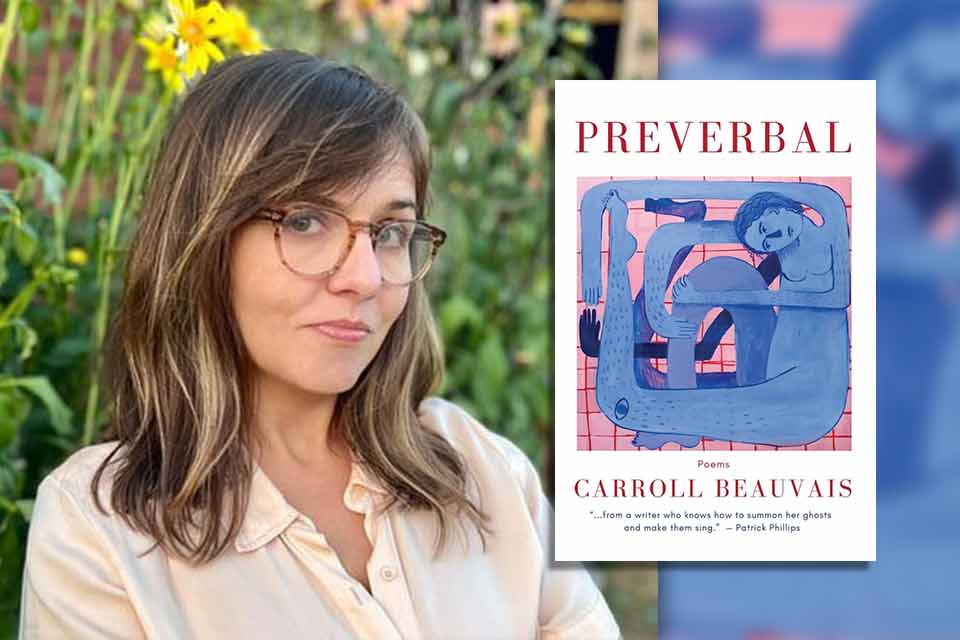

Translating Grief Outside Itself: Carroll Beauvais’s Preverbal

As a trauma therapist, I felt a deep chord strike inside of me while reading Carroll Beauvais’s debut collection of poems, Preverbal (Lit Fox Books, 2025). Positing the question, “What does trauma leave behind?” Beauvais reduces notions of memory to a mere flawed effort to rewrite history in a way that makes the unbearable, bearable. Her poems are not the tightly manufactured kind. They’re wild, reaching creatures that maul language into obedience, to fit their dysrhythmia. There is no gentle sustaining here, only the unflinching honesty of incomplete survival, set against a diorama of ghosts, as in the poem “Sunday Afternoons with Father,” where she reveals that“I know a skilled stillness, / the want to slip away.”

Some writers seek to shock and titillate; others, to unearth the ignored embers of grief and their inevitable truths. Beauvais may have honed her craft through education, but the experiences of her life and her refusal to look away and nullify what occurred lie at the heart of her writing:

Marilyn died from an overdose,

and you from cancer. Meanwhile, Daddy was at the crack house

with the pedophiles, but only because they shared.

(“How to Calculate Your Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Score”)

Beauvais’s refusal to look away and nullify what occurred lie at the heart of her writing.

Later in the same poem, aside the wry social commentary on the failure of systems or deprived notions of safety, nestles a raw-edged purity to Beauvais’s writing that claims the reader’s attention repeatedly, permitting us to shadow her in this horror-house of memory, without succumbing to its darkest messages: “Did you ever figure / how many moments of self-deprivation until you starve / from lack of life?”

Can grief ever be translated outside of itself? Poetry can be a vehicle for emboldening secrets and dressing them brightly enough that their purpose remains long after reading, in a corner of your mind that mulls over the impossibility of this degree of loss and savagery. At times, reading this work is uncomfortable but necessary, inhabiting the experience of a punctuated life enduring these deficits. Poetry, alongside art, film, and dance, can evoke and replay scenes, enjoining the notion of art with trauma in a tangible symbiosis. Heart-clenching metaphors abound here, exquisitely rendered and truly preverbal, the symbolism and colors evoking such a stark tableau set against the intelligence and miniaturized messages in the poem’s titles.

As with life, it is what is unsaid that has the greatest power. Beauvais’s writing is courageous, but I focus most on her uncanny insight into her ancestry and selfhood, how her descriptions are preverbally lush in their power to paint for the mind’s-eye the terrible vignettes of memory:

He’s fixed on some

unseeable flame behind me. Licking the corners of his mouth, he watches

until it flickers out.

(“Caretaking at Ryan’s Steakhouse”)

We are in a world filled with horrors but also love; that is the most poignant but also tragic element.

We are in a world filled with horrors but also love; that is the most poignant but also tragic element; for all the rage, dysfunction, and betrayal, she still loves, and in that, while there is no room for breathing, there is room for a strange, fractured hope, observing that “They trample those tall sunflowers / that have yet to learn they will die” (“Fight / Flight”). Raw-throated loss is depicted with an alluded nod to more, in the poem’s titles, alongside filmed-moments, drawing dangerously close:

I climbed in her hospice bed,

pressed my face to hers, and told the lie the nurses

said would help her most: I’ll be okay, Mama. You can let go.

(“Dress Rehearsal for the Un-Dead”)

Beauvais has allowed us in, standing by her testimonial unself-consciousness, not asking anything of us. Her own life is acknowledged for its fragility, the debris of the past weighing in time and again:

You died, and I tried suicide.

And you died, and you died, and you died, and you.

(“Fragment from the Mountain of Things I’m Not Allowed to Speak”)

Using the simple power of a repeated phrase “you died” becomes musical, the lyricism of grief, hypnotic and intoxicating in its swaying, strange beauty. With titles like “Nostalgia Was a Mental Illness Until the 20th Century,” this book’s title is a nod to Bessel van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps the Score, specifically the line “All trauma is preverbal.” Colleen Terrell Comer’s haunting painting Knotted illustrates the mazelike quality of unerringly climbing out of trauma, and Preverbal stands as an uncanny impression of loss, permanently inked to our urge for something real.

Grasse, France