Palestinian Novelist Sahar Khalifeh: Exploring the Nakba and Gender Politics in Palestine

If Palestinian literature is truly a literature of exile—one that focuses on memory and redeeming the geography and lives shattered in 1948—the Six-Day War in 1967 brought about a different tradition of writing, a kind of literature that tried to capture the moment and realize the evanescence of the dream of return to Palestine. In the newly occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip, a contemporary generation of writers started to see things through a different lens, to tackle issues and subjects more concrete and close to the lives of Palestinians under Israeli occupation. Before the 1967 war and the Israeli occupation of the entire territory of Palestine, a great deal of the literature written by Palestinians living in the diaspora, in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, as well as by Palestinians living in lands that became Israel after the Nakba (i.e., catastrophe) of 1948 was nostalgic, focusing on the dream of return and trying to capture moments lived in a receding modern Arab Andalucia. But the newly emerging voices in the West Bank and Gaza Strip after 1967—cut off now from the Arab world and its culture, facing new realities, living the Nakba again, and suffering the vicissitudes of occupation, under siege, and isolation from their fellow Arabs—started to write a different kind of literature, a literature that chronicles and portrays their suffering and living under the harsh circumstances of a people under occupation.

Emerging from this context, we can see the literary output of the renowned Palestinian novelist Sahar Khalifeh. Born in 1941 in the city of Nablus, located in the northern part of Palestine, and in what came to be known as the West Bank of the River Jordan after 1948, her talent flourished after the Israeli occupation in 1967. Although her first novel, We Are Not Your Slaves Any Longer, was published in 1974 and focused on the theme of liberating Arab women from what Khalifeh called being “a member of a miserable, useless, worthless sex,” her fame grew after she published her second novel, Wild Thorns (1976).

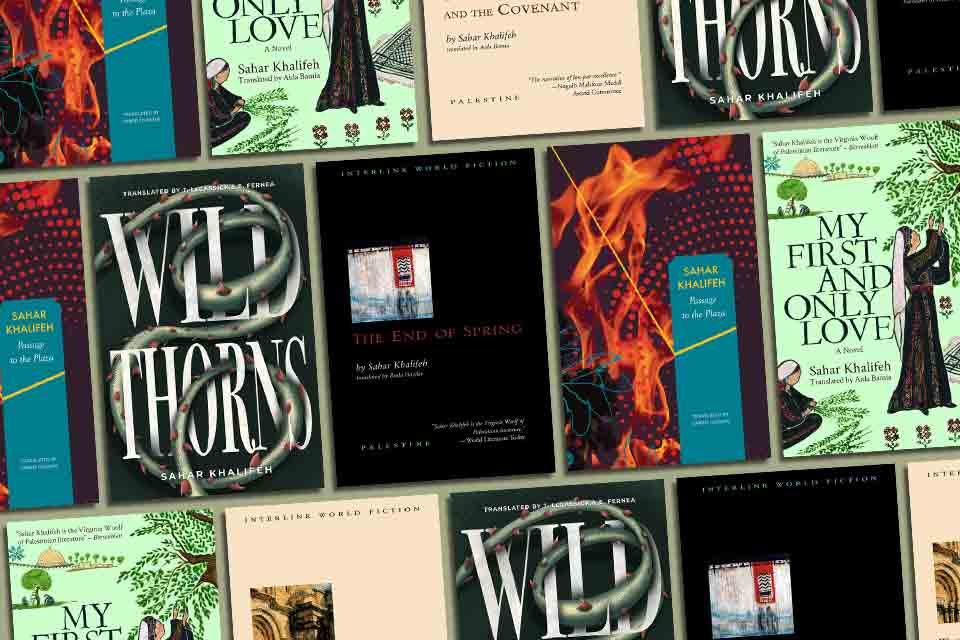

The work of Sahar Khalifeh has been translated into English and published in the US, the UK and Egypt. Of her eleven novels, seven of them have appeared in English, starting from her widely read second novel, Wild Thorns, released by Interlink in a Kindle edition in 2021. Her historical novel My First and Only Love was published by Cairo’s Hoopoe imprint in 2021.

Wild Thorns paved the way for a different type of writing in the occupied Palestinian territories and gave a new voice to marginal issues and characters (see WLT, Spring 2000, 451). We must, of course, bear in mind that the novel was written in a literary field that praises resistance: armed resistance, when the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) became recognized as the sole representative of the Palestinian people. In such a political and cultural milieu, Khalifeh explored issues of Palestinian society, including class struggle, gender, discrimination against women, and the minor role of women in resisting the Israeli occupation. Wild Thorns paints a real, concrete, but harsh image of Palestinian life under the Israeli hegemony. It blames the occupation for the disintegration of the economic and political structures of the Palestinian society, confiscation of land, and the imprisonment of Palestinians, but it does not spare Palestinians from criticism. Vividly aware of her role as a woman in an occupied country, underprivileged, and abused in a traditional oriental society, the writer does not succumb to clichés nor to social and political taboos of the era.

Wild Thorns paints a real, concrete, but harsh image of Palestinian life under the Israeli hegemony.

The characters of Wild Thorns represent different strata of the Palestinian society—middle class, proletariat, and the old feudal crumbling of Palestinian society—as well as intellectuals, working men and women, businessmen, and uneducated men and women. These characters interact under the stressful circumstances caused by the occupation. In a literary style that fuses daily utterances with reminiscences of the past, discussions of class struggle with feminist aspirations, Khalifeh dwells in the consciousness and ordeals of her characters. In Wild Thorns, the reader recognizes the brutality of the Israeli occupation and the necessity of liberating women as well as men. The path to liberation is not only armed struggle but, first and foremost, the creation of a healthy society free of discrimination against women and underprivileged citizens.

The Sunflower (1980), which is a sequel to Wild Thorns, focuses primarily on the position of women in Palestinian society and thoroughly discusses the Palestinian patriarchy and the struggle of women to liberate themselves from the entanglements of a traditional social system. The novel is a fictional exploration of the necessities of liberation and freedom, of society as a whole, in order to battle against the Israeli occupation. The female protagonist of The Sunflower wrestles with her limitations as a journalist, writer, and woman in a social and cultural milieu that resists change.

The role of women in an occupied country, and the continuing struggle to liberate themselves from being controlled and alienated by men, is integral to Passage to the Plaza (1990), which chronicles the events of the First Intifada (uprising) in 1987. The novel sheds light on the gender divide that looms over a resistant but traditional society, aspiring to liberate itself from a cruel, even barbaric, colonial occupation. The feminist outlook, fed by a Marxist analysis of Palestinian society and politics, prevails in most, if not all, of Khalifeh’s novels. The lingering traditional role of Palestinian women forms the heart of Khalifeh’s fictional world. As a result, the slow progress toward gender equality in an occupied, resisting, brave people is central to the message of her work. The message delivered to readers is drawn from simple men and women, from the underprivileged, who resist the occupation and continue to find their way in life. Generally, the upper classes, intellectuals, and those in privileged positions are not the primary victims of Israeli colonial and imperial occupation.

The slow progress toward gender equality in an occupied, resisting, brave people is central to the message of Khalifeh’s work.

Khalifeh’s fictional portrayal of gender and the politics of love and marriage could be traced back to her first published novel, We Are Not Your Slaves Any Longer, as I mentioned earlier. However, this recurring theme of gender and the position of women in traditional Arab societies, and in Palestinian society in particular, is fully explored in her novel Memoirs of an Unrealistic Woman (1986). The novel is a long monologue of a lonely Palestinian woman who lives with her husband, after forced marriage, in a city in the Arabian Gulf. The protagonist recounts her childhood, including her passion for painting, the early love of a boy from a lower class, and being dispatched to her husband who works in the Gulf, to finally experience a miscarriage and divorce. In this semi-autobiographical novel, Khalifeh paints the gloomy psyche of her character as well as the barren landscape of the Gulf city where she was forced to live with a female cat. The protagonist forms a strong bond with the cat, seeing the animal as her double, a kind of liberated, free creature that she desires to emulate.

Although Khalifeh’s later novels shifted toward quasihistorical fiction about Palestine, before and after the Nakba, incorporating historical and documentary materials written about Palestine by Palestinian, Western, and Israeli researchers, issues regarding gender remain fundamental to her fiction. In The Image, the Icon and the Covenant (2002), she writes about love across the barriers of religions, alluding to the landscape of Jerusalem and the battle waged by Israelis to change the face of the sacred city and cleanse the city from its Palestinian natives. The love between a young Palestinian Muslim man and a young Palestinian Christian woman ended up becoming a nightmare, with the girl pregnant and disappearing in a monastery. The story, narrated by the man after he became old and returned to Palestine from the Gulf as a rich man, is the background to the larger story of the Nakba, the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, and the rift that separates people on the basis of religion, class, gender, and education.

Although Khalifeh’s later novels shifted toward quasihistorical fiction about Palestine, before and after the Nakba, issues regarding gender remain fundamental to her fiction.

There are two other novels that deserve to be mentioned: On Noble Origins (2009) and My First and Only Love (2010). The latter is a sequel to the former, and both of them chronicle the political and social history of Palestine in the first half of the twentieth century. On Noble Origins takes place in historical Palestine, from the 1920s to 1930s, moving between Nablus, Haifa, and Jerusalem. It attempts to capture a lost, evanescent Palestine while narrating the struggle over territories between the Zionist movement and the Palestinians, with the British Mandate helping the Zionists to acquire the territories and evict the Palestinian natives from their homeland. The novel critiques the traditional, backward, and discriminatory practices against women within Palestinian society, and these critiques can be found in the novelistic description, dialogue, and monologues of female characters. The novel describes the failure of the Palestinian revolution of 1936, against the British Mandate and the Zionists, due to political disputes between different factions of the revolution and the conspiratorial role of Arab rulers, mostly under British colonial rule, at the time. In On Noble Origins, Khalifeh draws parallels and comparisons between the Palestinian and Jewish societies in historical Palestine, reflecting on the organized, heavily armed, Jewish society in comparison with the unorganized, poorly armed Palestinians.

My First and Only Love is a story about the fall of Palestine in 1948 (see WLT, Spring 2021, 90). A sequel to On Noble Origins, it features the same characters in addition to new ones; Palestinians, Jews, British, and Americans populate the fictional landscape of bravery, martyrdom, sacrifice, betrayal, and agony. Alongside its chronicling of the Palestinian Nakba and the fictional historical portrayal of political figures, the novel fuses the events with the remembrance of a love story. The female narrator sifts through her uncle’s memoirs, handed over to her by the man she loved since she encountered him during the Palestinian revolution in the 1930s. The daughter discovers, upon reading the papers, that her mother was deeply in love with Palestinian leader and revolutionary Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni (1907–1948), who was killed in a battle against Zionist forces in 1948.

Like the previous novel, My First and Only Love gives ample space to discussions of gender and the role of Palestinian women. But in these two novels, Khalifeh draws a thin line between gender issues and the political struggles of colonized and occupied nations. She emphasizes both issues but realizes that being occupied by a colonial, military state like Israel should force Palestinian men and women, hand in hand, to revise the historical realities that led to the fall of Palestine, the destruction of Palestinian society, and the dispersal of its people to different parts of the globe.

Works Cited

Al-Sabbar (1976), translated into English as Wild Thorns (Interlink Books, 2003)

Abbad Al-Shams (The Sunflower), in Arabic, 1980

Bab al-Saha (1990), translated into English as Passage to the Plaza (Seagull Books, 2020)

Modhakkarat Imra’a Ghair Waqi’yya (Memoirs of an Unrealistic Woman), in Arabic, 1986

Soura wa Ayquna wa A’hd Qadeem (2002), translated into English as The Image, the Icon and the Covenant (Interlink Books, 2007)

Asl wa Fasl (2009), translated into English as On Noble Origins (American University Press, 2012)

Hobbi al-Awwal (2010), translated into English as My First and Only Love (Hoopoe, 2021)

Amman