Clara Luper’s Diamonds and Acts of Radical Love: A Conversation with Cornel West

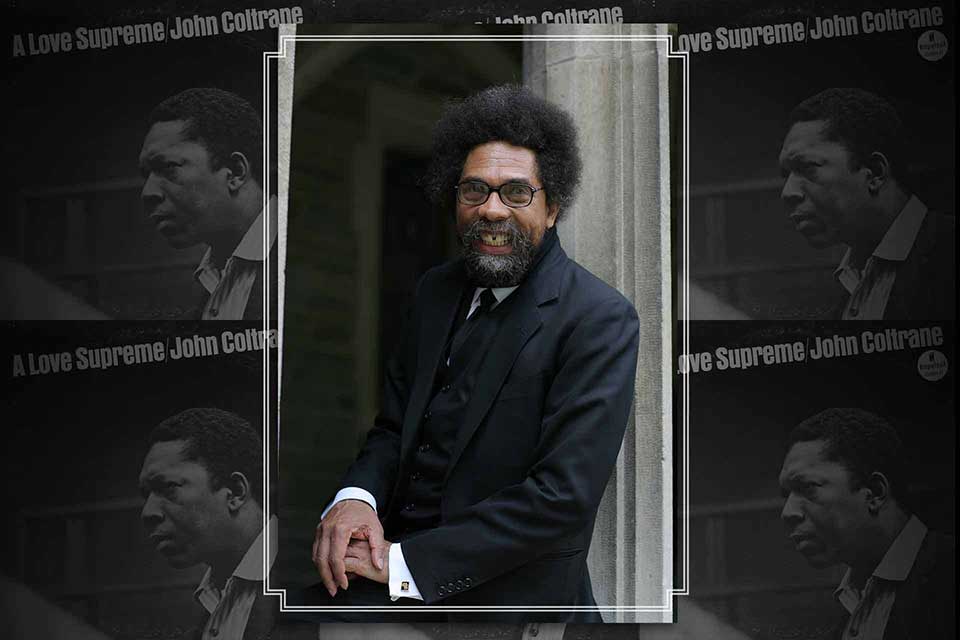

Cornel West, who recently retired from Princeton University as the Class of 1943 University Professor in the Center for African American Studies, visited the University of Oklahoma late last week. He was on campus to take part in OU’s Presidential Speaker Series in a point/counterpoint discussion, “Saving America: Conflicting Views in Civil Dialogue,” with his Princeton colleague Robert P. George. Dr. West graciously sat down with me before that conversation to take part in the following exchange for World Literature Today. The following excerpt concluded our conversation.

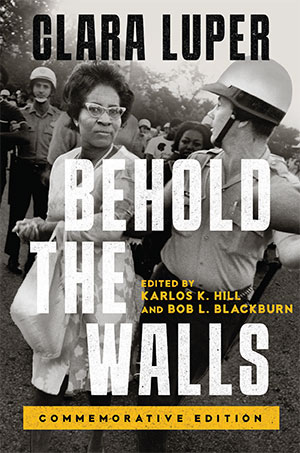

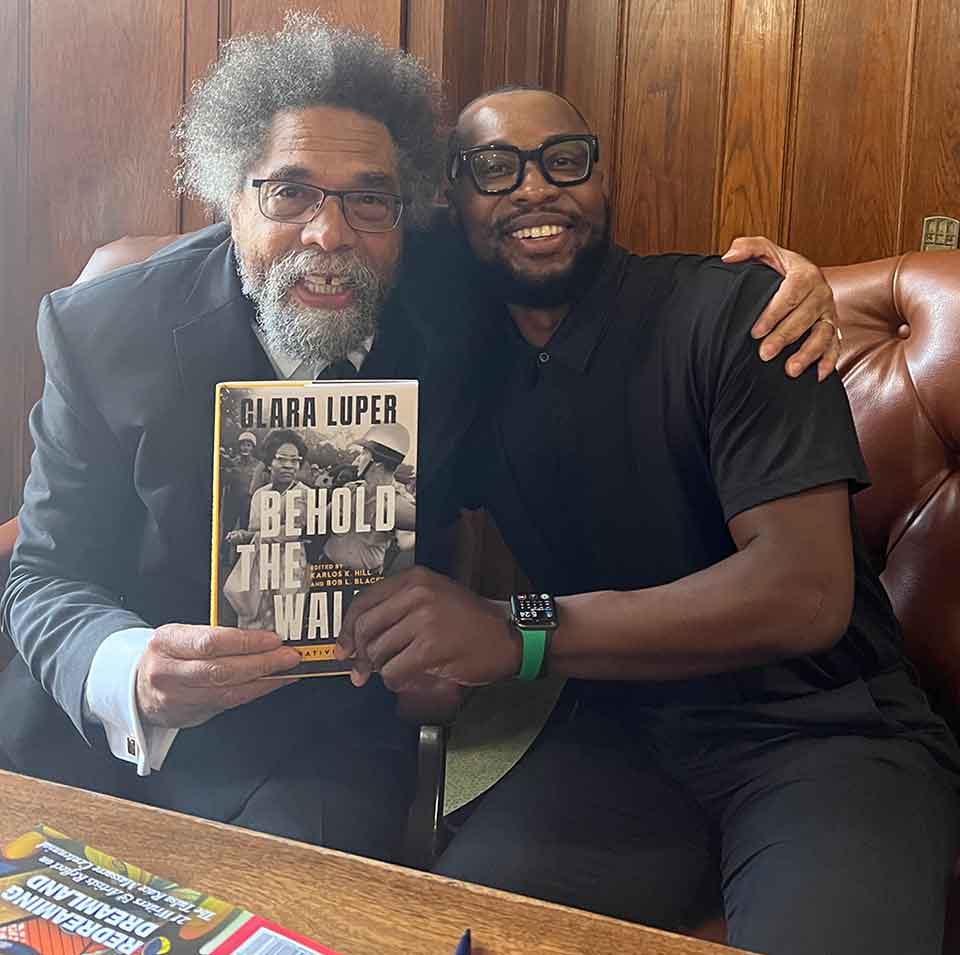

Hill: Brother West, I would like to share a book with you. This is a gift to you: Clara Luper’s Behold the Walls (University of Oklahoma Press, 2023). I know you are familiar with Clara. The book had been out of print for at least a decade.

Hill: Brother West, I would like to share a book with you. This is a gift to you: Clara Luper’s Behold the Walls (University of Oklahoma Press, 2023). I know you are familiar with Clara. The book had been out of print for at least a decade.

West: I saw on your Twitter feed that in the last couple of days, you had an anniversary?

Hill: Yes, the sixty-fifth anniversary of the Katz Drugstore sit-ins. We brought together many of the original thirteen participants in that Katz Drugstore campaign that led to the desegregation of fifty-three stores in 1958. We brought them together to remember that, but also for a documentary that we hope to be able to pitch to the History Channel or PBS. To tell the story, to help do what needs to be done, which is to help the world understand what Clara Luper bore witness to, her profound legacy. On the sixty-fifth anniversary, not only did we get her memoir of that movement republished, but we also had a teachers’ institute in Oklahoma City where we brought together sixty-five teachers to do a workshop based on this book to help them figure out lesson plans and curriculum around Behold the Walls, her memoir of the movement. We had them here for a week. The point I’m driving home is that we focused on two concepts in the Clara Luper Teachers’ Institute. First, freedom’s classroom: Clara Luper as a master history teacher, someone who taught them so much about how to fight, how to struggle, how to be in service to people. And also how, as someone who was a devotee of Dr. King and Gandhi, she really inculcated in her students not just nonviolent disobedience, but she really impressed upon them the need for radical love.

West: Is that her language?

Hill: She doesn’t use the language of radical love, but what she tells them to do is engage in radical love. She tells them, she coaches them to endure the abuse, the mistreatment. Because we’re not here just to desegregate these lunch counters, we’re here to help the very people who are oppressing us. We can stand here and, through radical love, love people who don’t love you. Love absolutely.

West: That’s the kind of love I love. That’s it.

Hill: Brother West, that’s where I’m going. I would love for you to just talk about radical love, Clara Luper’s radical love, and the transformative impact that it can have on the catastrophes you mentioned earlier.

West: I’m just convinced that human beings are wretched in so many ways. The history of the species is very much the history of structures of domination, histories of hatred, what the great Howard Thurman called the hounds of hell unleashed: hatred, greed, fear, resentment, envy. I have a very grim philosophical anthropology, in some sense. Christians call it sin, but on the other side of that wretchedness, there’s a wondrousness and wonderfulness, like that last line of Chekhov’s great short story, “The Student,” reflecting on Easter. How is it that this wonderfulness, this wondrousness, can still be found given all the blood in human history and all the wounds in the history of the species. For me, acts of radical love are higher forms of courage that try to push back the wretchedness that is so dominant inside of all human beings. I do believe that there’s a civil war taking place over the soul of every person. They have to make a choice. When you choose not to hate back, therefore, what you’re doing is trying to elevate the relationship, the tradition, and the future to a level of moral and spiritual greatness that might not have the chance of a snowball in hell, in terms of its consequences. That will be a shining example of an integrity that could touch people’s hearts, minds, and souls to keep the tradition alive.

Acts of radical love are higher forms of courage that try to push back the wretchedness that is so dominant inside of all human beings.

You see, it’s not utilitarian calculation, it’s not just political strategy. It’s at the deepest level of what it means to be human. That’s Sister Clara. That’s Martin. That’s Coltrane’s Love Supreme. That’s Stevie Wonder’s “Love’s in Need of Love.” That’s the love. That’s what Baldwin says about love: it forces us to take off the mask. We know we cannot live within, but fear we cannot live without. That’s existential. You don’t need a lot of Kierkegaard, even though that Danish genius helps. But Baldwin, he’s working this out in his own distinctive way with his own genius. That’s the kind of radical love I’ve always been committed to.

That’s why in the end, back to the twenty-fifth chapter of Matthew where you talk about the least of these, it will never make sense through the eyes of the world, the dominant ways of the world. It will never make sense because in the dominant eyes of the world, it’s Thrasymachus over Socrates—might makes right. Power dictates morality. Socrates has an integrity he’s trying to pass on to the younger generation in The Republic. Glaucon and Adeimantus, let me give you an example over against this gangster who’s trying to tell you to conform to the dominant ways of the world. Thrasymachus has all the evidence in the world.

Hegel says history is a slaughterhouse, you know? Gibbon says it’s a series of human crimes and follies. They’re right—in part. But there’s something else too. Clara will tell you what that something else is, not by means of utterance solely but by her example. I mean, she lives it. That’s a very different thing. Like the conclusion of an Aristotelian practical syllogism; it’s not a proposition; it’s a life lived. That’s the conclusion I would see. Now, I don’t know her background. She’s probably a church sister.

Hill: Well, what I say to people, trying to help them understand, is that Dr. King was a minister/activist; Brother Malcolm was a minister/organizer; and Clara Luper was a teacher. That’s where she was rooted. She wasn’t rooted in the church like Dr. King.

West: Was she shaped by growing up in the church?

Hill: She was. She preached radical love because it came from a Christian ethos.

West: Her soul craft. Do you remember the name of her church?

Hill: Yes, we had our final program for the sixty-fifth anniversary on Sunday at Fifth Street Baptist Church in Oklahoma City. What we’re trying to accomplish with Clara Luper is to get people to see her as a master teacher. And we taught the teachers in the institute that the era of the master teacher isn’t over, and that even in an Oklahoma that’s banning books, that’s stifling creativity, stifling just the whole environment. Deborah Gist, the superintendent of Tulsa Public Schools, has been harassed, harangued, and finally she gave me into that and resigned her position because of refusing to be silent about what’s happening. So, she’s one of the fatalities. It’s not just the teachers, it’s also the administrators. We’re reminding them that there are courageous people like Clara Luper, master teachers who center radical love both in their activism and their teaching, centering students. Clara Luper called her students diamonds. It’s trying to get people to understand.

We tried to do two things this year: the hundredth birthday of Clara Luper, we celebrated that on the steps of the state capitol, which was really important to highlight unity in the community. That’s something that Marilyn Luper, her daughter, thought was important. The second thing is the sixty-fifth anniversary of the Katz Drugstore sit-in, and bringing together those activists to reflect on how that one sit-in helped galvanize the Greensboro sit-in in 1960. And that’s the link which makes Oklahoma really matter in the national story: through the NAACP network, because the activists in Greensboro are part of the NAACP Youth Council, they learn about the success of sit-ins from Oklahoma City.

Part of what I’ve been able to bear witness to is we have been able to assemble all the documentation to show that. So, it’s not just the memories of Marilyn or the memories of some of the activists. We actually have NAACP minutes showing the ways in which that there was a presentation from the Oklahoma group in 1959 at their annual conference, where they won an award for the youth council chapter. And the news of their success was shared there. From there you see, not necessarily a direct line, but what Marilyn and many try to say is that a successful precedent was established, news of its happening. And then you saw, months later, Greensboro emerge and then the rest.

West: I was just talking to Brother Amos Brown, the pastor at San Francisco’s Third Baptist Church for forty-nine years. He took that church over after Freddie Haynes, his father, dropped dead in the pulpit. This is the Freddie Haynes whose son just took over the Rainbow Coalition of Jesse Jackson, pastor of Friendship–West Baptist in Dallas, Texas, for the last thirty-five years. Amos was at that NAACP meeting, either in New York or somewhere on the East Coast, when there was a presentation reflecting on what was going on in Oklahoma City with the folk from Oklahoma City. And the young brother who was sitting there was the brother who went back down to Greensboro, where it didn’t take off at the first meeting in the fall. Then, at another meeting in January, it did take off. But there was a direct line because that little young brother was sitting up there in the meeting when they were reflecting on it at the NAACP gathering. And Amos Brown was in that same meeting. You know Brother Amos, right? He knows that history, doesn’t he?

Hill: Yes, he does. We had him speak at the sixtieth anniversary.

West: Is that right? See, you’re light-years ahead of me.

Hill: No, sir. I just I just know these people, they’re a part of this community, trying to lift up this story.

West: That’s exactly right. He’s always the first one to say, don’t talk to me about Greensboro if you don’t know nothing about Oklahoma City. That’s his thing. He didn’t get into Miss Clara’s name. He just talked about the group.

The radical love of Clara Luper was that she believed each of her students, no matter what, had amazing potential.

Hill: Yes, she was all about the students. And the students were her diamonds in the rough, right? You know, the radical love of Clara Luper was that she believed each of her students, no matter what, had amazing potential. You just had to spend the time with them to illuminate it. She had this radical belief that everyone could learn and everyone could reach their full potential. What was radical about her is she truly spent the time to mine it, she really did.

West: It reminds me of my mother, actually, Irene B. West—there’s an elementary school named after her right outside of Sacramento. She was the first Black principal, and the first Black teacher as well, in the school district. She was known for being the teacher in the vacation Bible school in Shiloh Baptist Church, right there in Oak Park, which is like the south side of Chicago. The young kids would come in from outside of the church. She did that for so many generations that you could just walk through the community and someone would say, oh, that’s Mrs. West, I remember she taught me when I was nine, I was eleven, I was thirteen. And she let us into the church even though we weren’t members of the church because they had food and everything. Between 9:00 and 12:00 they had these little gatherings, and that kind of impact of being a care lover and tenderer of young people’s hearts, minds, souls, and bodies, that’s what greatness is. That’s it. It doesn’t get better than that.

Hill: And Brother West, when you talk to Marilyn Luper about who her mother was, you can talk about a lot of different things. How she went to jail twenty-six times. Or you can talk about not only her central role in the sit-ins but also in the sanitation strikes or running for the US Senate, her radio program. But what Marilyn wants to talk about, going back to her mother’s selfless devotion to her students, is for fifty years she took a group of students, as many students that wanted to go, to the NAACP National Conference, members of the Youth Council, she always took upward of fifty-plus students who never, ever had to pay for a hotel room, never had to pay for a flight, a bus ticket. She found a way. This is what Marilyn said. She found a way every year for fifty-plus years.

West: Oh, my God. That’s it. That’s the bottom line right there. That’s what Ashford and Simpson would call the real thing. That’s the real thing.

August 24, 2023

Editorial note: A longer excerpt from this conversation will appear in the January 2024 issue of WLT. Karlos Hill’s conversation with Marilyn Luper Hildreth appeared in the May 2023 issue.