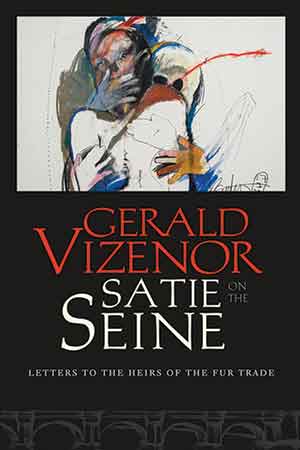

Satie on the Seine: Letters to the Heirs of the Fur Trade by Gerald Vizenor

Middleton, Connecticut. Wesleyan University Press. 2020. 354 pages.

Middleton, Connecticut. Wesleyan University Press. 2020. 354 pages.

THE PREFACE OF Satie on the Seine announces fifty letters written by Basile Hudon Beaulieu from Paris, France, to family and friends living on the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota between 1932 and 1945. These “Chronicles of Liberty” are written by the descendant of a Canadian-born fur trader who befriended members of the Anishinaabe Tribe during his travels in the northern territories. Gerald Vizenor himself counts several Beaulieus in his ancestry, a centuries-long friendship with France that continued in the twentieth century. Befriending World War I veterans Basile the writer and his artist brother, Aloysius, is Paris publisher and gallery owner Nathan Crémieux, whose character might be based on Adolphe Crémieux, a distinguished nineteenth-century lawyer and progressive politician of Jewish origins, or on the late Jean-Louis Crémieux-Brilhac, World War II resistor and historian of note. Set up as ironic witnesses and freedom fighters, these three semifictional protagonists embark on a historical voyage.

Chapter 1, a charming evocation of a young woman playing a piano piece by Eric Satie on a barge near the Pont de la Concorde, makes it clear that Satie on the Seine cannot be read on its own. The weave of time and plot is too deeply anchored in two previous volumes, Blue Ravens (2014) and Native Tributes (2018). Each of these three works centers on a major event: the service of Basile and Aloysius on the Western Front in World War I (Vizenor lost a relative, Augustus Vizenor, at the Battle of Montbréhain in October 1918); their march on Washington, DC, with the Veterans’ Bonus Expeditionary Forces in the summer of 1932 (a relative of Vizenor, nurse Ellenora Beaulieu, participated); and the firsthand witness of the coming of war and of the German occupation of Paris during World War II by the three main protagonists and their entourage of Natives, European refugees, and French resisters. This monumental triptych of awakening and confrontation contains numerous parallels between the situation of Native Americans and that of European Jews in the age of colonialism, repression, and dictatorship. Only the full knowledge of this epic saga allows the reader to acquire the same level of alertness and ethics as his quasiprophetic characters.

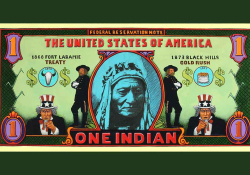

While each letter of Satie on the Seine is dedicated to a major event in European and French history such as the Front Populaire or Kristallnacht, and with thirty-seven letters covering the wartime period, Vizenor does not just use well-known events as props. He occasionally reveals illuminating details, as in his description of the massacre of Oradour-sur-Glane that is based on the little-known local police report. He also uses numerous verbal clues. One is the tireless use of ironic stories; another is the frequent use of the word “totemic” to describe Native peoples’ spiritual roots in nature. The most important of those totems are the countless “blue ravens” either painted by Aloysius on canvas or hand-drawn in space as incantations, blessings, or prayers for the healing of land, traditions, and peoples. Yet another clue is the fractured rhythm of the prose. Pithy, bitingly ironic exclamations by Aloysius and his Native American friends punctuate the text. Puppet shows in the tradition of Native “trickster” characters feature “parleys” between Hitler and Gertrude Stein, Joseph Goebbels and Henri Bergson, and Carlos Montezuma and Émile Zola. Artists’ meetings in Paris are interrupted by hurried rosaries of names afraid of forgetting someone. All these techniques highlight an ethos of resistance—the setting of survivance.

Disconnected by these linguistic and metaphoric techniques, the story’s elements, not unlike chess pieces, symbolize multiple man-made exiles from nature, from the land, from cultural and spiritual traditions, and from humanity. Vizenor’s sympathy for and tribute to the oppressed is visible as he contemplates environmental damage, poverty, injustice, exploitation, corruption, and hopelessness. Finding primal authenticity is helped along by the very repetition of stories, words, and scenes. The juxtaposition of real historical events with the adventures of post-Indian warriors battling victim stories and debunking colonial representations brings to a stunning climax this epic story of Native Americans in the crucible of the twentieth century.

Alice-Catherine Carls

University of Tennessee at Martin