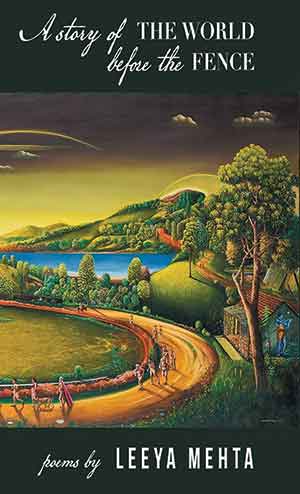

A Story of the World before the Fence by Leeya Mehta

Georgetown, Kentucky. Finishing Line Press. 2020. 46 pages.

Georgetown, Kentucky. Finishing Line Press. 2020. 46 pages.

LEEYA MEHTA’S remarkable recent verse collection charts one woman’s attempts to isolate and identify a sense of heritage, a lineage that she may hold close in the midst of the push and pull of her own profoundly dislocating life.

This book is ultimately a work of the refugee, and one that illuminates the fastening, unfastening, and refastening to location, language, and people that the refugee must endure. The larger question, however, is what will sustain an exile through these seemingly endless changes. What is immutable? What is real?

The collection begins with a dramatic vision of the migration across the Arabian Sea that brings Persians to India, but even as the boat pounds over the waves and the priests light their sacred fires, we are told that “all the joy and blood that had come before” is already “turning to myth.” Once in India, the migrants struggle to adapt while maintaining their own sense of community: “they are told: keep your stories whole but separate . . . keep your fire lit . . . but do not take our children into your temples.” It is as if a people unmoored are already fated to an obscure decline.

Moving deftly through time, the speaker considers India’s first nuclear test through the troubling thicket of identity. If these warmongers are indeed her people, “belonging,” we’re told, feels like “loving a corpse” and yet: “don’t my children need to know who we are?”

As the collection coalesces around a single voice that brings us into the present day, its scenes range from Maine to Japan to Washington, DC, charting a record of family lost and friends gone and love sparking into life, fading, and sparking again. Mehta’s poetry is by turns euphoric and despairing, as though she feels at moments something like the truth of her life rising to the surface of her experience, only to fall back once more into shadow, “close enough to hear, but not to see.”

And what is that truth? It is a sense of belonging that both sustains and frustrates the poet, one that is intuited and yet impossible to locate. Can she find it in her husband, who does not share her heritage? Her children, who understand it even less? Could it be in her friends, women who are so firmly of their own place and time, so much like the speaker and yet so different? Does it indeed reside in the Bombay that she would call home, or does it depend on the vanished empire her ancestors fled over a thousand years ago? Mehta’s answer to this fundamental question—only made manifest in the final poem, providing the resolution to a tension that has been building so subtly throughout the book that only its ecstatic release fully illuminates the work in total—is something earned, lived, and offered up in the hope that it may sustain us, as much as it may indeed sustain her.

Cameron MacKenzie

Roanoke, Virginia