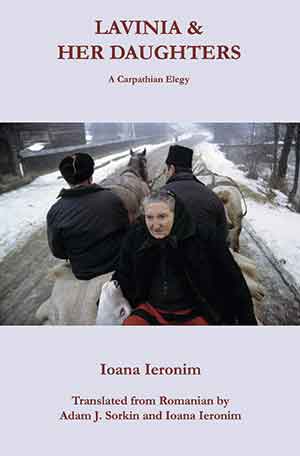

Lavinia and Her Daughters: A Carpathian Elegy by Ioana Ieronim

Somerville, Massachusetts. Červená Barva Press. 2020. 109 pages.

Somerville, Massachusetts. Červená Barva Press. 2020. 109 pages.

EVERY ONCE IN a while, a poet finds a new way to body forth in verse their cultural reality. Lavinia and Her Daughters, which can be experienced as a follow-on companion with a previous volume by Ioana Ieronim, The Triumph of the Water Witch (2000), is such a body of work.

In four sections (Prologue; Works, Days, and the Sliding of the Ground; Newcomers; and Epilogue), the poet spills across these pages such an immersive, sprawling, yet somehow essentialized experience of rural Transylvania, in Romania during the former Ceaușescu regime, that we cannot help but give ourselves over to it. Details accumulate in poetic fragments of varying form—fragments of speech, of familial life, of landscape and the furtherance of story—as girlhood and womanhood, religion and agriculture, life rituals and gossip all take shape with an aggregate weight of authenticity and coherence, adding up to an offhand, earned reverence one rarely finds in verse.

There is sudden cruelty and its slow aftermath, and the expansive magic that closeness to nature can bring. There is criminality and solidarity, delight and the politics of the unspoken. Night and the sun, labor and the dance of human emotions—all feel as palpable as characters in this dense landscape and progression of days.

The layering of these elements, in the juxtaposition of fragments, is the poet’s singular achievement here. Ieronim has taken the idea of the white space of line ending as a compositional element in formal verse and here transposed it to the space between fragments—more is said in the interstices than can be communicated in words.

Then Vasile cracked his whip at him, with its lead tip.

That was all.

The old man fell, softly, in the grass.

The sheep went on grazing in the waning of the afternoon, their bells ringing

softly. What do sheep know?

Nobody punished Vasile, he was only a child. That way he was left unfor-

given . . .

Now nobody greets him, asks after his health, shares stories with him. When

he opens his mouth,

people reply curtly, with displeasure.

“Where there wasn’t a punishment, the punishment grew inside him:

he never laughs, never laughs.”

A girl, barely a teenager, in her pleated skirt and with a basket in

each hand,

hurries by Vasile, her face hard as glass.

How much this Vasile works! Much more than the Haiducs . . .

Where sin chases, yes, the heart is a cinder.

The dignity with which Ieronim stakes out her characters places this work in the higher realms of poetry. Too, as translator Adam J. Sorkin points out, despite the panoply of the ever-unfolding local, the poet’s language stays in the register of the familiar rather than relying on dialect, lending to the work a certain universality, also in English translation.

One should look all the way to a poet such as Czesław Miłosz for suitable comparison with the achievement here—an apt comparison too, in light of Ieronim’s stint as cultural attaché and her other roles in service to literature and culture most widely.

Andrew Singer

Trafika Europe