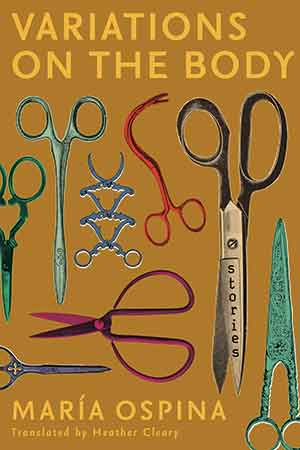

Variations on the Body by María Ospina

Minneapolis. Coffee House Press. 2021. 136 pages.

Minneapolis. Coffee House Press. 2021. 136 pages.

IN MARÍA OSPINA’S first book of short fiction, Variations on the Body, each story lets the reader into the life of a different woman living in her body in Bogotá, Colombia. Originally published in Spanish, the collection paints a picture of a city and country grappling with the ghost of an internal war that has been going on for over half a century.

The stories vary in length and subject but consistently return to the theme of control. Against the backdrop of ongoing war within their country, the women’s lives go on. They get pregnant, go to work, get and give bikini waxes, learn to write, travel. Some women attempt to control their own narratives by way of controlling their bodies—removing battle scars, handling unexpected pregnancies—while others are intrigued to the point of obsession by the narratives and bodies of others.

Men exist on the periphery, but these are women-led and women-focused stories. It creates a sanctuary effect; the things shared in the stories will stay between the characters and the reader. The dialogue is strong, ordinary without being boring. Much occurs beneath the surface of transactional interactions—a phone call, an exchange on the street, a business letter from New York—which kept me on my toes, on the lookout for hidden meaning.

This subtlety also betrays the book’s weakest facet: sometimes the dramatics of a scene are not played up correctly, or at all, which left me wanting. For example, in “Policarpa,” the book’s first story, we see the narrator vomit at the sight of an old woman. Later, the narrator tells a story about an old woman she knew while serving as a soldier, which explains why she had such a visceral reaction to seeing the old lady. However, the foreshadowing wasn’t smooth enough to build the tension needed for me to feel truly affected by the pathos of the explanation.

I found it helpful, when reading, to look for changes in awareness. In “Policarpa,” as the story goes on, the narrator, formerly a Marxist soldier, becomes increasingly aware of the things she lacks in comparison to others. As her awareness grows, she develops a personality that didn’t exist at the start of the story. Conversely, in “Saving Young Ladies,” brutal and compelling like a car crash, Aurora becomes continually less aware of the dangerous nature of her obsession with one of the teenage girls living in the convent next door. Meanwhile, the reader becomes increasingly aware of the wrongness of Aurora’s attraction and more concerned about the nature of her character.

Translator Heather Cleary clearly pays homage to the original Spanish in her translation; words not traditionally used in English, yet which are common in Spanish, remain peppered throughout the work. Furthermore, her translation blends so seamlessly with the writing that most of the time it is easy to forget this is a work in translation.

Throughout the book, Ospina manages to address themes of control, intrastate conflict, and women’s bodies while keeping her reader inside the story. The book never abandons the narrative to explain what is happening or why. Variations on the Body assumes we know about the ongoing war in Colombia, what a carrefour is, and are familiar with doll-repair shops. But Ospina’s descriptions, when she utilizes them, are vivid; “Fauna of the Ages” is wholly dedicated to communicating to the reader the singular agony of battling against flea bites.

An excellent example of a first book of fiction, Variations on the Body personalizes hardship through concrete individual actions, asking more of its readers with every sentence.

Zoe Goldstein

Harvard University