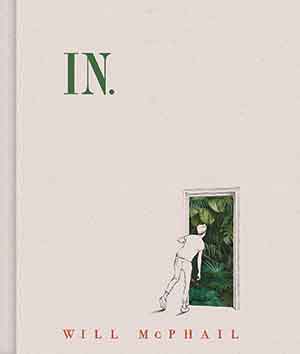

In.: A Graphic Novel by Will McPhail

New York. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2021. 272 pages.

New York. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2021. 272 pages.

IN AN ERA WHEN alienation and anomie are daily topics, Will McPhail’s graphic novel In. will resonate with many readers. His tale follows one fellow, Nick, from a brief glimpse of his childhood happiness to a young adulthood spent, it seems, moving from one coffee place or bar to another. Reflecting the gig economy, he tells us that, as a freelance illustrator, he tends to work in public places.

McPhail has great fun with these gathering-places-cum-work-stations, giving them terrific names and portraying them in well-drawn black-and-white scenes. Who wouldn’t want to drink in the “Your Friends Have Kids Bar” or grab a latte in “Gentrificciato,” or a macchiato at “Artisanal Kick in the Back” where the Wi-Fi password is “Dialogue Is Not for Exposition 2007.” Nick frequents them all as a loner, until one day he meets Wren.

But this is not a boy-meets-girl scenario; it is, rather, a scenario about a young man evolving, moving forward a few steps and then back a few. Authentic interaction with another human being is not easy for Nick, and much of this novel takes place in his head as he struggles for connection. The graphics finally explode not with sex but with Nick finding emotion, first of all, oddly enough, in a breakthrough conversation with a plumber when each of them admits his embarrassment and awkwardness in the world. The page turns, and we are in a world of intense color and dream-worthy landscape. McPhail brings us to his own version of Oz within Nick’s mind.

There is a great deal of verbal and visual wit here, wit that can be seen in much of McPhail’s work as a cartoonist for the New Yorker and Private Eye. A section where Nick is interacting with clients trying to direct his creative energies is filled with priceless babble and offers incisive observations about creative work designed by a committee. Asides about typefaces and his repartee with Wren are also witty but mostly superficial until the book turns much darker and Nick has to come to terms with his inability to relate to the world as an adult. Charmingly, his nephew creates color in Nick’s world with honesty, as does his mother, who demands to be seen as not only Mum but Hannah.

While this first graphic novel showcases McPhail’s style in the simple black-and-white drawings and outrageously gorgeous colorscapes, there is not enough depth to his characters to truly engage us. The story does turn heartbreaking but, ultimately, leaves us feeling that the narrative arc is thin. There is so much more to be fleshed out and felt in the world he has created. Maybe in his next work, or at least I hope so.

Rita D. Jacobs

New York City