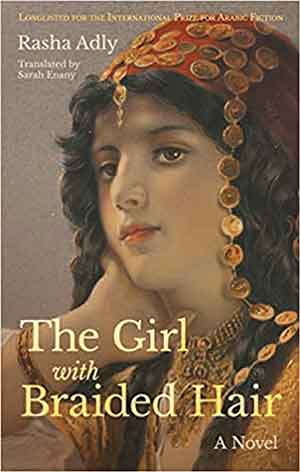

The Girl with Braided Hair by Rasha Adly

Cairo. Hoopoe. 2020. 324 pages.

Cairo. Hoopoe. 2020. 324 pages.

RASHA ADLY'S NOVEL The Girl with Braided Hair tells parallel love stories, with one set in contemporary Egypt, post-2011 uprising, and the other during Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt. The main character in the present, Yasmine, an art history professor, is intrigued by a painting from the French occupation—and the novel revolves around solving the mystery of the Egyptian girl’s identity in the painting and the story of the painter, who was not listed in Napoleon’s official retinue.

The basic premise of the novel—the quest for the “lived story” behind a historical object—is a deceptively promising one. Abd Al Rahman Al-Jabarti’s The Marvelous Compositions of Biographies and Events is certainly the right historical source for this novel since he witnessed the French invasion of Egypt. Writing historical fiction is a tightrope act for a writer, balancing between historical fact and storytelling with characters who should seem as flawed and human as our friends and neighbors. One should acknowledge the ambitious idea for this novel; however, the book is a mélange of orientalist stereotypes, soap opera clichés, and a pastiche of previous novels that have dealt with similar themes or premises.

The most engaging sections of the novel are those that rely on Al-Jabarti’s account, incorporated into the painter’s diary of his experience during Napoleon’s occupation. For example, the painter describes the First Cairo Revolt in 1798 when Egyptians rebelled against the tyranny of French occupation: “None had forgotten the scene when Al-Azhar had been violated, when they had galloped on their horses and blasted off cannons, burning and defiling the Quran.” He also describes the dire situation during the plague: “The corpses were washed with vinegar in lime, then transported on ox-drawn carts, these carts whose bells and squeaking never stopped sounding.”

In other places, historical detail is not always folded in so seamlessly. Quite frequently, dry facts are delivered through dialogue that sound like art history lectures. Yasmine goes to France for an art history conference, where she meets up with another expert who provides her with clues to the identity of the anonymous painter. Many of their exchanges are basic historical facts about Napoleon’s expedition, facts that a professor would already know.

Character and plot echo soap-opera melodrama and cannot be substituted for carefully drawn characters who feel palpable and respond plausibly. For example, Yasmine’s mother killed herself because her father had an affair. Upper-class Egyptian women might be enraged by their husbands’ infidelity, but it just doesn’t ring true that they would kill themselves over a single affair. In the parallel story during the French occupation, could Zeinab, the girl in the painting, become fluent in French in such a short time? The painter in love with Zeinab, who is dying of bubonic plague, begs Zeinab to come and see him on his deathbed.

Of course, writers might be influenced by the literary tradition or even the current literary market, but one is reminded a little too obviously of Girl with a Pearl Earring (1999), by Tracy Chevalier. Chevalier’s novel focuses on the famous Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer—and the servant in his house, who modeled for his eponymous painting. Zeinab, “the native Egyptian” girl, catches the eye of Napoleon and an obscure painter, Alton Germain, who is part of his expedition. She is pimped out to Napoleon by her father, Sheikh El-Bakhri, a collaborator with the occupiers. Like Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion, she is reeducated and redressed by Napoleon. At the same time, he is excited by her exoticism—and she is told to belly dance for him after he has given her a lecture on Cleopatra.

Sufism is conjured briefly in the tale but disappears just as quickly. Other novels have done this more successfully. For example, the Arabic novel The Snow of Cairo (2013), by Lebanese novelist Lana Abdel Rahman, explores the story of a young Syrian woman coming to terms with her identity and purpose in life, weaving themes of reincarnation and Sufi mysticism within a suspenseful narrative of self-discovery and understanding of the past. The Turkish novelist Elif Shafak’s The Forty Rules of Love (2009) also has a parallel story that explores the synchronicity of characters from the present and the past with Sufi themes. Here, we are given a lecture on the basic tenets of Sufism through dialogue when Sherif, Yasmine’s boyfriend, has his spiritual awakening in Konya. It is odd that the novel, which was written originally in Arabic, assumes that Arabic readers would not have the foggiest idea about Sufism.

Writing about sex and love is a challenge for any writer, but fresh language can make the experience surprising for the reader. Yet Adly falls back on stock phrases from romance novels. Even if translator Sara Enany is mimicking the translation of a Frenchman into English, the translation seems stiff and unnatural. In the painter’s diary, he worries about Napoleon’s intentions toward Zeinab: “The man’s words inspired fear and worry in me. Was this man truly grooming Zeinab to be his bedmate?”

The novel concludes with Yasmine in France, solving the mystery of the girl in the painting from the French occupation of Egypt. We learn the fate of the Egyptian girl as well as the artist who loved her, who was punished by Napoleon and his work excluded from museums and the Description of Egypt. Yasmine feels that she has been sent a message through the painting like “a voice sent through ether.” The message is unclear to the reader. Is it a feminist critique that a sixteen-year-old courtesan will always be broken on the rack of conservative society? Or does the author’s ambition remain at the level of a dime-store romance?

Gretchen McCullough

American University in Cairo