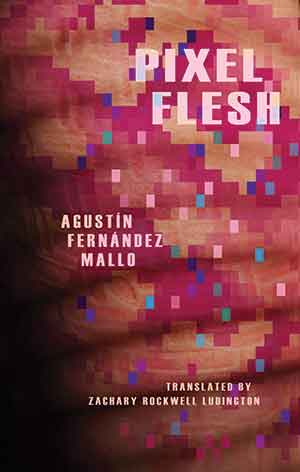

Pixel Flesh by Agustín Fernández Mallo

Phoenix. Cardboard House Press. 2020. 128 pages.

Phoenix. Cardboard House Press. 2020. 128 pages.

WITH AGUSTÍN FERNÁNDEZ MALLO’S Pixel Flesh, translated by Zachary Rockwell Ludington, Cardboard House Press brings to readers the first English translation of the poetry of a noted Spanish advocate for the intersections of art and science in “postpoetic poetry.” Mallo is a radiation physicist working in biomedical engineering on cancer therapies and author of The Nocilla Trilogy. Pixel Flesh emerges from the idea that science is human creation and representation, which must therefore have an aesthetic dimension. Through the premise of pixel as the smallest unit containing visual information, Pixel Flesh sets out through repetitions and fractal, fragmented snapshots to circle around a scientific aesthetic on the page.

This is a conceptual work, and the text is designed to show more than it says. The movement of time in the text resembles electromagnetic rays, both wave and particle; “I saw clearly at that instant [sum of instants],” the speaker reflects. The prose poems progress in iterative descriptions by a first person addressing an abstract “you”; what has elsewhere been read as love is perhaps better described as shared experience, obsession, and projection. Mallo’s interest in writing through cultural detritus informs this approach of using a set of trite tropes that generate a loop and ultimately demonstrate the deterioration of meaningful human connection in the face of technological static. The text repeats images of the speaker and his subject circling the city, crying in the rain, offering a Lucky in a vintage aura of recycled frames.

Translator Rockwell Ludington reflects in the translator’s note that “it is repetition that most profoundly marks this collection of poems [poems? Polaroids? samples?]. The repeated scenes and pop references constitute and define the speaker and his partner, but this repetition also means each image or attitude is a copy of something prior, at the same time eager to transfer its anxieties to its next incarnation.” The translation becomes itself a rich commentary on the representation of fractal self-similarity. Ludington explores how to knowingly translate oddness in the original, exposing the valences of fractal deriving from the Latin for “broken” or “fractured.”

Concrete images dissolve as the speaker posits that memories and people “mutate into fleshless characters, just vectors of ideas.” The speaker addresses a “woman” who remains only ephemeral, the feminized subject of the speaker’s projections. The speaker admits, “It’s true, there was a lot of night, rain, a woman, etc., but in reality I’m only talking about myself, because that’s all I have.” All perception becomes the projection of this detached, mechanistic, heterosexual masculine figure evading the “slime of true contact.” This archetype of the basic unit of Enlightenment science attempts to continue self-replicating as it becomes more evident that the only relationship which exists is with his own manufactured representation.

Mallo employs poetic form in a pertinent conceptual commentary on virtual spheres and the technological wastelands bisecting human relationships.

Honora Spicer

El Paso Community College