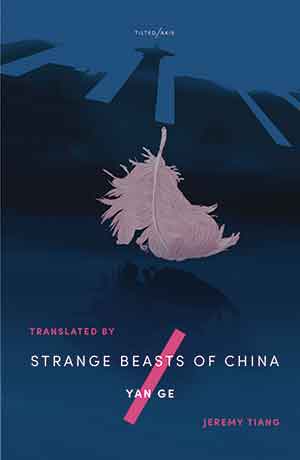

Strange Beasts of China by Yan Ge

Sheffield, UK. Tilted Axis Press. 2020. 220 pages.

Sheffield, UK. Tilted Axis Press. 2020. 220 pages.

YAN GE’S Strange Beasts of China immerses you in its world through a series of interconnected tales, each one focusing on a different type of fictional beast that lives in the city of Yong’an. Through these tales, a writer, with a background in zoology, seeks the truth about her own identity. Her world is one of deception, insults, and cruelty; and it is against these forces that she tries to assert her agency through writing.

The book maintains a lighthearted tone that, accompanied by the sometimes bizarre behavior of the characters, gives the tales a whimsical feel but never dulls the impact of the dangers the writer faces while navigating her world. Indeed, it often contributes to a sense of tragedy, which pervades the narrative as a whole. For instance, one of the most striking things about the tales is how they are full of laughter. This laughter, however, is often propelled by anxiety and heartache. The construction of a text with such a mixed tone, which never becomes jarring, is one of the highest achievements of Yan Ge’s book and that of her translator, Jeremy Tiang.

In many ways the tales are difficult to categorize into a single genre. They have elements of magical realism, romance, fairy tale, and also a strong dystopianism. One of the most dystopian tales is “The Heartsick Beasts,” in which we are introduced to beasts who have been manufactured to be companions and moral guides to children. These beasts are created to be temporary, and after a certain number of years they are removed from their families. The writer, as with the beasts in the other tales, aims to bring light to their hidden stories. In many ways this forms part of the book’s meditation on the importance of writing in exploring, and making sense of, the world. It can be used to perpetuate or challenge, and it can also be a way to seek identity and catharsis.

The sometimes-complicated twists of the narrative mean that it benefits from a rereading. The threads leading to the revelations at the end become clearer, and an understanding of the narrator develops. A rereading does not dampen its disquieting and mixed tone, however, nor does it reduce the impact of the psychologically threatening situations that the narrator faces. The book is unsettling and remains so. Prospective readers should expect to be presented with a narrative world in which answers are actively hidden from the narrator while pushing for explanations leads to cruel rebukes. This does not mean that there is no room for a cautious optimism within the narrative, though, and this optimism is provided by writing.

Rachel Franklin

Nottingham, United Kingdom