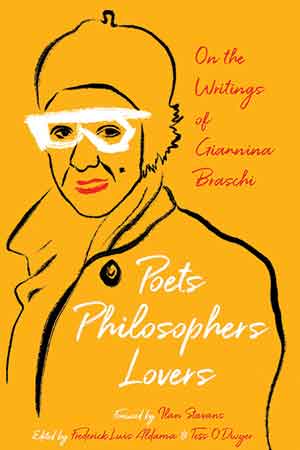

Poets, Philosophers, Lovers: On the Writings of Giannina Braschi

Pittsburgh. University of Pittsburgh Press. 2020. 168 pages.

Pittsburgh. University of Pittsburgh Press. 2020. 168 pages.

PUERTO RICO–BORN and New York–based Giannina Braschi is a strange writer. A poet and a novelist, over the last four decades she has published three books—the first, El imperio de los sueños, in Spanish; the second, Yo-Yo Boing!, in Spanglish; and the third, United States of Banana, in English. Together, these form a trilogy of sorts, a nonstop literary romp, which moves from experimental prose-poem, to novel, to theatrical dialogue. They are all shot through with a consistent philosophical and political exploration of the limits and ethics of language, the relationship between freedom and the imagination, and the Puerto Rican colonial situation. If it sounds excessive, it is. Braschi’s contemporary reader—educated after the postmodern heyday—is often at odds to explain what is happening, how it is allowed to happen, and why—despite all this—it works so well.

Poets, Philosophers, Lovers: On the Writings of Giannina Braschi is a collection of academic essays that attempts to answer these questions using the tools available to contemporary literary scholars: contextualization, comparison, exegesis, critique, and theorization. Edited by Frederick Luis Aldama and Braschi’s translator, Tess O’Dwyer, the book’s main thrust is to reintroduce Braschi to a wider academic public and reframe her, through the critical lens of the day, as “one of today’s foremost experimental Latinx authors.” For Aldama and the book’s contributors, Braschi participates in a long, albeit less visible, branch of Latinx writing that has been and continues to be driven by aesthetic and literary experimentation rather than explicit realist representation—like Isabel Ríos, Cecile Pineda, Gloria Anzaldúa, Guillermo Gómez-Peña, and Salvador Plascencia. This tradition has largely been sidelined in scholarly inquiries into both the Latinx experience and aesthetic and literary experimentation.

Braschi’s oeuvre, as Madelena González writes in the first essay of the volume, populated as it is by migrants and questions of language, colonialism, and politics, would seem at first sight to cry out to be analyzed from within the existing critical parameters of “postcolonial studies” and the study of “world literature.” Beyond mere obliviousness, then, why has its impact remained limited to certain literary and scholarly niches, alien to those who seek texts that tackle these problematics? For González the answer is simple. Take a book such as Braschi’s United States of Banana. Immediately upon reading, you will notice how it “obstinately refuses to conform to the protocols laid out for it.” Braschi uses “formalist concerns and the potency of style” to question and lay waste to “accepted values and interpretative strategies” at every level of the work, making most straightforward analysis troublesome. Anne Ashbaugh, another of the contributors to the volume, holds that Braschi’s writings participate in a constant motion that “prevents analysis” and makes it “impracticable to resort to traditional hermeneutical strategies.” In other words, both scholars insist that the challenge found between the covers of Braschi’s books is that these insistently work toward interrupting our literary expectations and critical habits at every twist in the road, making the reader uncomfortable and blowing her out of the water over and over again.

The best way to engage with Braschi, for Ashbaugh—and this applies to the tradition of experimental Latinx writing mentioned above—is, instead, to go along for the ride and think with her; to create a conversation between the work and the many other thinkers that pop up among her pages and explore and examine what might result. In her essay, for example, Ashbaugh stages a philosophical dialogue between Braschi and Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, a figure that is also fictionalized in United States of Banana. The comparison allows Ashbaugh to clarify the relationship between freedom and art in the text, and she concludes that whereas Nietzsche “frees the Will that has been colonized by religious paradigms,” Braschi “frees Latinx creativity that has been colonized by empires.” Both Nietzsche and Braschi, she writes, “share this concern for strengthening the human will, and they resort to creative experiences in order to instill self-worth in an otherwise ineffectual will.”

Like Ashbaugh’s, the best contributions to Poets, Philosophers, Lovers are those that engage in a similar manner with Braschi’s work, not by strictly analyzing its constitutive elements but by going along with it. Another such trip that deserves mention is Ronald Mendoza de Jesús’s, where a recurrent line in Braschi’s United States of Banana is put into a dialogue with Jacques Derrida that is, surprisingly, a pleasure to read. By unraveling Braschi’s refrain and engaging with her slippery and playful deployments of ideas of freedom, and then doing the same with Derrida’s last works, Mendoza de Jesús sheds light on what is and has always been at stake in Braschi’s (and Derrida’s) oeuvre: a resistance to the politics of power, to any force that preaches the ethics of servitude and obedience. For Braschi, as Madelena González points out, that resistance is embodied in the author’s commitment to art and poetry as practices of an insurgent, critical imagination.

Appropriately, Poets, Philosophers, Lovers closes with a conversation between Giannina Braschi and a scholar, Rolando Pérez. At one moment of their sprawling and meandering conversation, Braschi recounts an anecdote that captures something that I believe is essential in her work. Braschi is eighteen and living in Madrid. There, she meets an older poet whom she admires. The older poet applauds Braschi’s own work, sighs, and tells her that “to be a poet when you’re eighteen, twenty, that’s easy, but to be a poet when you’re fifty, that’s something else.” Something about those words echoes with Braschi, now an “older poet” herself, and she tells her interviewer: “How can you continue to believe in poetry, after all the blows that life has dealt you? How does one still believe in feelings and innocence?” She might not have had an answer to the question when she was eighteen, but today, we can say that over the last four decades, her work has offered a solid rebuttal and shown a path to continue believing in poetry’s force, not despite the battery of life and history but because of it.

Sergio Gutiérrez Negrón

Oberlin College