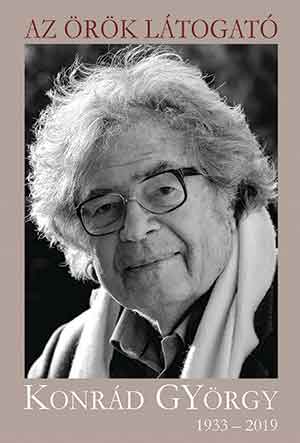

Az örök látogató – Konrád György (1933–2019)

Budapest. Noran Libro. 2020. 264 pages.

Budapest. Noran Libro. 2020. 264 pages.

THE HUNGARIAN WRITER György Konrád passed away in September 2019 at the age of eighty-six. His death is commemorated in a book of reminiscences and tributes by fifty Hungarian and foreign writers, journalists, and friends. Konrád was well known outside Hungary thanks to his presidency of the International PEN Club (1990–93) and the German Academy of Arts (1997–2003), as well as through frequent reviews of his books in the English-speaking world.

The present collection, Az örök látogató (The eternal caseworker), compiled by József P. Kőrössi and edited by Károly Szarka, consists of three parts: individual reminiscences, selected views of Konrád’s first novel, The Case Worker (A látogató in Hungarian), two interviews (Pál Várnai, Júlia Váradi), plus a warmly nostalgic evocation of Konrád by his widow, Judit Lakner. Most contributors rate highest among Konrád’s many books The Case Worker, The Loser (A cinkos), and Anti-politics (Anti-politika). One could add to these the more recent essay-novel Leaves in the Wind, Archeological Dig 1 (Falevelek a szélben, Ásatás 1), discussed by this reviewer in World Literature Today (May 2018).

As is usual on such occasions, the personal reminiscences vary in terms of both length and quality. The most memorable are by friends such as Róza Hodosán, László Lengyel, and the sociologist Iván Szelényi. More anecdotal, but in some ways rounding out the picture, are pieces by the Berlin-based György Dalos and Konrád’s German translator, Hans Henning Paetzke. From these we learn about such curiosities as why Konrád was reluctant to attend concerts (though he loved music) and which of his fellow writers were secretly jealous of his international success. Four localities where Konrád lived for longer periods—Budapest, Berlin, Csobánka, and Hegymagas—are vividly evoked in several essays.

Az örök látogató also includes several texts on Konrád’s influence as a political thinker; in this context I found particularly interesting Csaba Gy. Kiss’s essay, which shows that the novelist’s pre-1990 writings and activities commanded respect even among his political adversaries. In fact, Konrád—by temperament not a political animal—after 2010 took a stand once again, expressing strong criticism of Viktor Orbán’s creeping authoritarianism, for as László Lengyel put it, “he had devoted his life to the cause of free and democratic Hungary.” Or in the words of the poet Mátyás Móritz: he “was more interested / in the truth than in power.”

Let us hope that posterity will remember György Konrád—novelist, essayist, sociologist, and political thinker—in the light of these estimable opinions.

George Gömöri

SEES–UCL