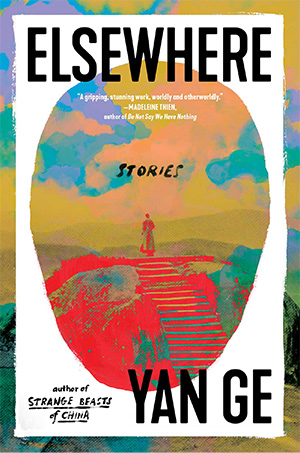

Elsewhere by Yan Ge

London. Faber & Faber. 2023. 304 pages.

London. Faber & Faber. 2023. 304 pages.

In her first collection of short stories written in English, Yan Ge presents tales that mesmerize and unsettle. Much like her Strange Beasts of China (2020), these stories offer the familiar, in that they have recognizable characters and locations, and strange, in that expected affect and context can subtly shift. For the most part, these are stand-alone stories, only “The Little House” and “Mother Tongue” sharing the same characters, but they all deal with similar themes: the power of words, how women go about making choices, birth and death, voices and silence, and the construction of identity within colonialist discourse.

Yan Ge uses nonlinear storytelling brilliantly, the stories unfolding rather than being expository. Her stories often begin in media res, and the context within which events happen to the characters is not always made clear, leaving the reader with an unmoored sensation accentuated by sudden bursts of body horror and swearing. The reader is never allowed to become too comfortable. In “Hai,” the longest tale, there is a punishment whereby a human is minced alive and then eaten. The body is transformed from whole to “mushed red flesh, putrified, oozing liquid.” The descriptions contain a discomforting relish that draws attention to the material aspects of our bodies.

The body horror, combined with the philosophical debates on time and writing in “No Time to Write,” and the musing upon identity-construction in “How I Fell in Love with the Well-Documented Life of Alex Whelan,” make the book as a whole difficult to classify. This seems intentional; another way that the texts encourage discomfort. The literary signposting within the tales, however, could be seen as a way in which the reader can orientate oneself. The most obvious intertext is George Orwell’s “Shooting an Elephant” (1936) in the tale of the same name, in which a Chinese woman, Shanshan, has her Irish husband’s dream of visiting Burma imposed upon her on her honeymoon. Other authors signposted are Camus, Kafka, Shakespeare, and Mishima, among others.

Even in tales where they are not overtly mentioned, one can see their influence. “When Travelling in the Summer” has Shakespearean intrigue and betrayal, while “Free Wandering” places Xiao Peng in a Kafkaesque landscape. This literary signposting can give the reader a way in, or at least something to grasp onto, after the startling beginning of the book and its discussion of geese intestines.

Rachel Franklin

Nottingham, UK