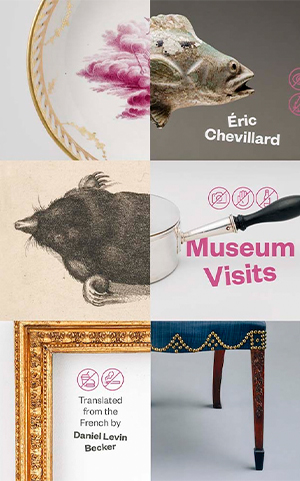

Museum Visits by Éric Chevillard

New Haven, Connecticut. Yale University Press. 2024. 152 pages.

New Haven, Connecticut. Yale University Press. 2024. 152 pages.

Fifty-nine-year-old Éric Chevillard is revered in France as one of its most original postmodernist authors. He has published twenty-two novels, written a weekly column for Le Monde, and blogged himself silly through many a restless night. The elite surely welcome him to their soirees, looking forward to being entertained by his outrageous musings. But when one looks closely at some of Chevillard’s most moving pieces, it is impossible to ignore a certain tenderness that rustles quietly beneath his text.

In his new work of beautifully rendered miniature pieces, Museum Visits, we hear the outlandish rantings of a man who finds the world fatiguing and suffused with needless idiocy. Chevillard claims he only feels alive while writing text, and we feel this intensity throughout these pages. It doesn’t surprise us that his idols are Beckett and Michaux because he believes they were beholden to no one, and he admires their bravado along with their disinterest in glory and reliance on their own instincts. We see that in Chevillard. He can slip into the narrative voice of a literary bandit or provocateur easily; in fact, he seems comfortable doing so. Many seem to think he is some sort of hardened absurdist who trades in clever mockeries and put-downs, but I see nothing of the sort. Despite his mock aggressiveness, I can only hear him crying for a relief that pathetically continues to elude him.

In his opening monologue, he ruminates about the places where “raindrops landed on Dante’s forehead” and “Vincent van Gogh combed his hair with his fingers.” In another meditation, he speaks of his love of writing, but uses the word ejaculating instead of writing, presumably to grab our attention. “Ejaculating saved my life,” he writes. “I’m not afraid to say it. If I hadn’t ejaculated I wouldn’t be here today. More than once I have wanted to die, to kill myself—yes—and instead I ejaculated.” He adds, “I deny nothing when I ejaculate.” We recognize that the word ejaculate, which caught us off guard, was put there to do precisely that. He needed to find a way to show us how writing has shaped and saved his life, and this struck him as the perfect solution to our sluggishness.

Elsewhere he discusses the idiocy of a chair, noting how annoying it is to bump into at night. He marvels at how when we sit in one, “in the space of a second, it breaks you into thirds.” We listen and laugh but recognize the chair actually scares him. It represents surrendering to the forces around him rather than fighting to live and write for another day. He sees the chair, despite its finite nature, as a sort of quicksand that can consume you if you are careless.

He visits museums not to see the work of the masters but rather to marvel at how the paintings are displayed. He loves looking at the floors of the museum and listening to the creaks they make when he walks gently upon them. As for the paintings, he focuses his eyes only on the frames. “Frames—now that’s something else,” he writes. “Speak to me of frames! Here is the highest expression of art, where it finally reaches its full potential.” When he accidentally catches sight of a painting, he is revolted by the same images of Napoleonic splendor, or Jesus on the cross, or some ceremonial burial. He describes his dismay: “My eye nerve revolts. My eye rolls back in its socket, and once again I take the bitter measure of my solitude. The enigma of the world is unbroken, my whole sensory experience brutally invalidated by mute, obtuse reality.”

In a simpler telling, he speaks about visiting the place where Hegel’s cap is displayed and wondering if any of the brilliance Hegel possessed is present still in his cap. Soon enough, he is describing his dismay with the sky, which he finds overrated and wishes it could be blocked from his view. He spends a few pages contemplating the life of his goldfish, wondering why it is so often still and then, unexpectedly, will start swimming around the small tank as if about to explode. What would cause such a change? Soon enough, he is off to his disgust with doors and his wish they could all be unhinged and turned into giant sleds we could ride around the world, seeing things that might make us understand the mysteries that surround us. Still elsewhere, he writes about the strange, exotic, engorged beauty of a face after it has met a fist for the first time; how it looks in its bloody splendor.

Whatever Chevillard is speaking about, he is always really talking about something else. We read him on both levels; understanding that his astonishing wordplay and absurdist fantasies are really stand-ins for the inner torments of his soul. We hear his desperation, and we mourn alongside him. But we laugh too, for he allows us to feel less alone. We somehow learn to see the world anew. A chair isn’t really a chair. The sky is only a big blotch of blue, and not even the prettiest shade of blue. Perhaps we leave parts of ourselves lying in different places we have visited without knowing we have done so. Like Hegel’s cap. Could it hold some of the secrets of Hegel’s brilliance? For once, we are not so sure. Chevillard has shown us that things are often not really what we think they are. We must continue to look, and then look again.

Elaine Margolin

Merrick, New York