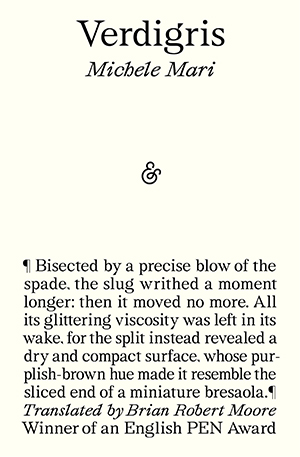

Verdigris by Michele Mari

Los Angeles. And Other Stories. 2024. 240 pages.

Los Angeles. And Other Stories. 2024. 240 pages.

Michelino has grown up spending summers at his grandfather’s estate near Lake Maggiore in northern Italy, immersed in the stories of horror and mystery from his grandfather’s library and captivated by the peculiar groundskeeper, Felice, an older man of uncertain age who appears both genial and frightful in Michelino’s young eyes. Now, on the cusp of the 1970s at thirteen years old, Michelino’s wonder and imagination over the groundskeeper’s nature increasingly occupy his mind upon learning of Felice’s onset of memory loss.

Yes, he was considerably ugly, he had a face bloated and deformed by growths, cavities, marks, scars; he had that purple . . . those encrusted and perennially shut eyes . . . he hawked phenomenal gobs of spit . . . then there was his intimacy with the terrible verdigris, as though immune to the poison, and the violence with which he butchered and skinned rabbits. . . . But was all this sufficient to turn him into a monster, or had my own will to supplement these qualities been necessary from the beginning? His recent memory loss, meanwhile—didn’t it only help to humanize him?

Though supposedly precipitated by an inherited disease, the memory loss makes the supposition hard to verify, as Felice’s parentage is lost to the fog of history, as are the records of how he came to be on the estate prior to its purchase by Michelino’s grandfather from exiles of revolutionary Russia. Michelino takes it upon himself to try and help the old man stave off memory deterioration through the use of mnemonic devices. Simultaneously, he interrogates Felice for any remaining recollections about the past. Gradually, Michelino’s investigation uncovers deeper mysteries, including a hidden room with skeletons dressed in Nazi uniforms, doppelgängers, blood-filled wine bottles, and legions of “French” red slugs that Felice zealously slaughters to stop voices that hauntingly speak to him from the earth.

In an interview with the New Yorker, Michele Mari has explained how his stories tend to “focus on a moment from [his] childhood, a period in which everything is fateful and foundational.” In Verdigris, Mari constructs a coming-of-age tale upon a gothic core. Michelino’s fascination with the engimatic and uncertain monstrosity of Felice and his ancestry represents that defilingly gothic desire to pursue what one fears, even knowing that “all knowledge ends in pain.” Michelino’s confrontations with Felice’s condition, and events of the past, propels him into maturity, with the previously frivolous curiosity of the unknown world turning inward, morphing into self-realizations.

. . . my condition has always been one of doubleness; although I have never succeeded in ascertaining whether this split is only psychological, or ontological too. According to Felice, inside of me lived both a dead person and a living person: must I consider myself a coward if I never wished to get to the bottom of the matter? The charm of that whole story, moreover, was bound up in the fact that it concerned another, not to mention those quintessential others who are monsters; but to discover that I, too, was a monster was not so amusing, especially if I had to trust what an old wine-guzzler told me.

Mari uses the gothic elements of the novel to explore changing perceptions of history and how truths lie between the factual and the storied. The title of the novel itself symbolizes this theme. Verdigris physically appears in the novel as the copper acetate solution that Felice spreads on plants to poison pests that would consume the crop. But, like much in the novel, there is a duality to that verdigris, a symbolic sense beyond the material. Verdigris implies a significance beyond the sense of blue-green, turquoise-adjacent color. Long associated with the renewals and rebirth of spring, natural verdigris is actually a constantly changing color. As with the Statue of Liberty made of copper that was once brown, only the passage of time and the chemical activity of oxidation has created the color we observe today. And it continues to change, even as we see flecks of the past within it. The title thus also ironically serves to contrast against the physical and mental decay of Felice.

Mari further mines the concepts of continual change and symbols to play with the ever-fluid nature of language. For each moment of macabre or darkness, Verdigris has twice as many passages of lighthearted humor that explore the nature and limits of reason and memory. The wordplay and love of language inherent to Verdigris makes it both enticing and exceptionally challenging for translation. In his afterword, Brian Robert Moore writes an illuminating perspective on this challenge, explaining the changes required to capture the joys of Mari’s Italian text, particularly the idiosyncratic dialect of Felice.

“So why call ’em pins? An’ to think ’f it, ’em thingsits in lasses’ hair is called pins too.”

“Yes, but clothespins are pins because they pin things down, I think, not because they have sharp ends that give you a pinprick.”

“Usin’ the same word for what a lass be puttin’ in her hair an’ for wha’s goin’ on her draw’s, sure ’t seeems mighty quare to me.”

Not long after this passage, Michelino notes that “by playing with words, one always ended up with the same result: nonsense.” Again, Mari uses irony here, highlighting throughout the rest of the novel the meaningful observations that come from his impressive manipulation of words.

Though Michelino is only thirteen at the time of the events of the novel, he relates things as a fifty-year-old character’s memories. As such, Michelino’s dialogue never reads like something coming from the mouth of a young teen. Instead, it is filled with the observations and experiences of a middle-aged man. This allows Mari to pair the coming-of-age plot with reflection that mines references from philosophy and literature, from the schema of Kant to the “what ifs” of Hegelianism; the horror of Lovecraft or Poe to Borges’s conundrum of whether a writer writes their story, or if the story writes them.

Verdigris is a novel full of connections between literature, metaphysics, and philosophy. There is a profound depth to it that could involve multiple readings to catch and appreciate. Yet the novel is also exceptionally readable and compelling, with excellent pacing and a central plot of mystery on its surface for readers to engage. The successes of this edition of Verdigris are certainly in no small part due to the talents and artistry of Moore in translating the book so effectively. I will now seek more work from a new author who is among my favorites. This is a magical novel not to be missed.

Daniel P. Haeusser

Canisius College