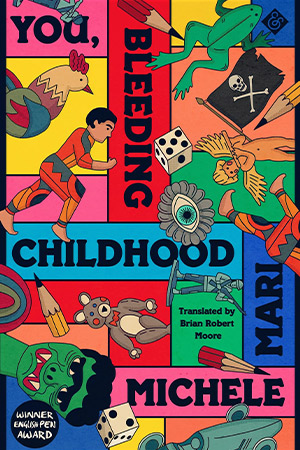

You, Bleeding Childhood by Michele Mari

Sheffield, UK. And Other Stories. 2023. 128 pages.

Sheffield, UK. And Other Stories. 2023. 128 pages.

If “childhood is another country” (as Saint-Exupéry suggested), few writers have mapped its topography, culture, and hidden cave systems as meticulously as Michele Mari in the prose pieces that make up his startling collection You, Bleeding Childhood. Originally published in Italian in 1999, the impressive English translation by Brian Robert Moore has now been released by And Other Stories. In parodic dialogue both with the elaborate literary anamnesis typified by Proust and with contemporary memoir (that easy effusion of retrospective anecdotage often mined for sentiment and nostalgie de la boue), Mari’s stories zoom in on the obsessive paraphernalia of a solitary childhood, bringing philosophical scrutiny to the comics, games, and genre fiction the young Michele would pore over and collect, reconfiguring the apparent frivolity of popular culture with the ludic panache of Roland Barthes in Mythologies.

Fetishized and fraught with subjective meaning, the treasured childhood artifacts Mari excavates from memory are also transitional objects (in Winnicott’s definition), vehicles for navigating the psychological journey toward individuation and managing anxieties about the adult world. In doing so, they also help foster interactions with the somewhat shadowy figures of his parents. When his father gifts him a book in the story “The Black Arrow,” it is invested with abnormal signification, since the son seldom sees the father—also, the fact that there could be two translations of the same text, two versions of the sacrosanct object, is a lesson in multiplicity, the unitary language of childhood fragmenting into the grown-up sphere of difference and plurality. Similarly, in “Eight Writers,” the succession of male maritime authors personified into heroic semblances (as though the authors had become their own doughty protagonists) may be seen as paternal surrogates imaginatively fleshed out via their tales of seafaring and adventure, transposed into the introspective loneliness of the boy Mari.

In “Jigsawed Greens,” he shares with his mother an obsessive passion for jigsaw puzzles, and another micronarrative of maturation is played out in the way that their symbiotic teamwork gradually shifts from maternal tutelage ( she “was the architect and forewoman, I the stonecutter”) to a level of extraordinary difficulty where “my mother was unable to follow me all the way,” increasingly undertaken as a separate, solitary activity. Again, the act of piecing together images through ever smaller components takes on a metaphysical dimension:

Following in these maternal footsteps, I learned the fragmentary nature of the world and the discontinuity of being, learned guilelessly the ways of gnosis, learned that no knowledge is granted that does not lead the multiple back to the singular or give form to what is formless.

“Jigsawed Greens” is also an example of how metafictive tropes are made to resonate throughout the book—all these childhood pastimes seem precursors to the formation of the adult writer, whose compulsion to make sense of experience through complex taxonomies of phenomena has its beginnings in these juvenile crazes. This assemblage of stories—beguilingly ambivalent as to how it is balanced between actual memories and fictive elaborations of them—is held up as another provisional taxonomy. In “The Soccer Balls of Mr Kurz,” even the old unseen neighbor, previously envisaged as a curmudgeonly hoarder (perhaps as deranged and misanthropic as his Conradian namesake), is startlingly revealed as an inveterate seeker of order, with nothing more to preoccupy him than the rare, fortuitous alighting of another stray football for his collection: an apt trope for the writer at his solitary desk.

Ultimately, You, Bleeding Childhood is a sophisticated, highly self-conscious work of fiction, playfully jamming together elements of autobiography and literary criticism against bizarre flights of imagination and fantasy, at times recalling the vertiginous fabulism of late Italo Calvino (an erstwhile mentor for Mari). For example, “War Songs” is chiefly concerned with the young narrator’s exhaustive, almost structuralist analysis of a single traditional song his mother used to sing to him, with its hauntingly macabre tale of a wounded, dying captain asking to be cut into five pieces. Yet the final two paragraphs spin off into a different, third-person narrative frame, with the dissection of the captain’s body being related as part of a story that veers strangely into science fiction mode (was the captain in fact an alien presence?) before again switching into the register of epic poetry, suggesting that war (and the war songs that arise from them) are both eternal and universal:

. . . and I, in certain nights, hear them, and think of Hecuba and Andromache, and say, barren land of Troy left sacked, land of Troy turned to glass, land loved ever more as time has passed, after light years and light years of railroad tracks.

Oliver Dixon

Hertfordshire, UK