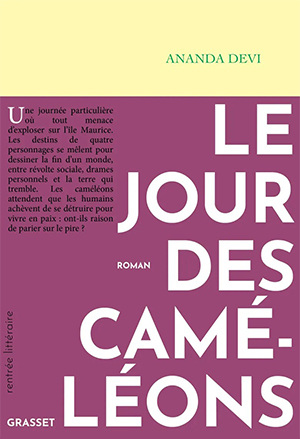

Le Jour des caméléons by Ananda Devi

Paris. Grasset. 2023. 272 pages.

Paris. Grasset. 2023. 272 pages.

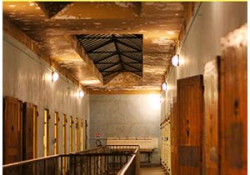

The Indian Ocean island nation of Mauritius, which is known for its ethnic and linguistic diversity, has produced three particularly notable novelists who write in French: Nathacha Appanah (whose latest book, La Mémoire délavée, was published in 2023); the 2008 Nobel Prize winner J. M. G. Le Clézio; and Ananda Devi (winner of the 2024 Neustadt Prize). Best known for such novels as Ève de ses décombres (2006), Le Sari vert (2009), and Le Rire des déesses (2021), Devi now lives in a French town with a remarkable literary history: Ferney-Voltaire. Her fifteenth novel, set in Mauritius, begins with the arrival of a small group of chameleons on the island. Having hitched a ride on a cargo ship, these ominously solemn characters will silently observe a developing ecological and social disaster, while telling themselves: “Le temps des hommes est compté” (Time is running out for humans).

In alternating chapters named after the main characters, the same series of events is successively and gradually narrated from differing points of view. While riding in a dilapidated car, the withdrawn and defeated René and his strangely mature young niece Sara come across Nandini, a middle-aged woman who has just left her egotistical husband but who now has nowhere to go. Meanwhile, a young street gang leader who goes by the name of Zigzig wakes up in pain, after having been beaten and left for dead. Now high on drugs, he is out for revenge against a rival gang. These mostly desperate inhabitants of the island will converge in an unlikely way onto a desolate stretch of the coastline, with devastating effects. Along with the human and animal characters, the volcanic island of Mauritius intermittently expresses itself, thus playing a role that is reminiscent of the chorus in a Greek tragedy.

The overall plotline of “The Day of the Chameleons” could be described as the slow unfolding of a foretold apocalypse, with hardly any instances of comic relief. Urban poverty, depression, drug use, rape, armed gang rivalry, and a massacre of tourists in an upscale area all combine to create a paroxysm of violence in one place, one day, at the end of which the chameleons come out to watch, even as a volcano is still rumbling portentously. Within the generalized chaotic atmosphere, there are isolated moments of redemption. The brutalized and brutish Zigzig, who is described in the last pages as a “leper messiah,” unexpectedly sacrifices himself to save the young Sara. However, this does not change the overarching thrust of the narrative, which depicts the downfall of society and of the island itself.

This allegorical novel could be categorized as part of the dystopian genre, but the storytelling ends at the tumultuous moment of societal collapse, the imminence of which might be construed as either limited to Mauritius or broadened to the rest of the world. At once somber and fascinating, Devi’s latest novel is one of her most memorable.

Edward Ousselin

Western Washington University