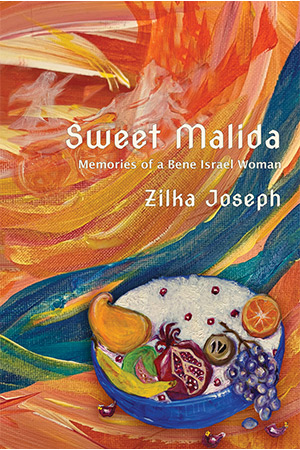

Sweet Malida by Zilka Joseph

Woodstock, New York. Mayapple Press. 2024. 66 pages.

Woodstock, New York. Mayapple Press. 2024. 66 pages.

I’m able to read Sweet Malida outside of my own Judaism and culture and appreciate Zilka Joseph’s meticulous research efforts on the subject of the Bene Israel Jews of India. She opens a doorway into a culture few in the West are familiar with. Malida refers to a typical Bene Israel custom, the preparation of ceremonial foods comprised of special ingredients particular to the people and their faith. When I add back my own Jewish heritage to my reception of Sweet Malida, I am overwhelmed by what Joseph has achieved. This Bene Israel woman has become a legitimized and enduring voice for Jews of Indian extraction, giving meaning and definition to a group of people with a fascinating history and juxtaposition within the myriad Indian cultures. Those who know of the community may still fall short of appreciating the challenge and beauty of being in two worlds, that of India’s rich tapestry and Joseph’s Jewish ancestry and faith.

Being Egyptian Mizrahi and French Sephardi Jewish myself, I intimately understand such hybridity. In a world where Judaism is dominated by the writing and culture of Ashkenazi Jews, the lesser-known groups’ unique cultures are often overlooked. Even Jews within the faith are unaware of these splinter groups and what they bring to the table of Judaism. Sephardi Jews, often called conversos because of needing to hide in Catholicism to avoid martyrdom, lost many of their cultural totems once in Mexico and are in the process of regaining them through an integration of their adopted Catholicism and the heritage of their ancestral Jews. Similarly, the Bene Israel had the bare bones of Judaism before Christians and Jews later reintroduced lost elements.

Identity, therefore, is hard to truly appreciate for someone outside this experience of assimilation and loss. Finding a way of locating this loss and reenergizing it through recognition and remembrance is hopeful and necessary to move forward. Like Joseph, I am also an immigrant to America, and located in her poetry, I recognize the same passions, sense of dislocation, and queried selfhood that I myself have contemplated. As a writer, Joseph strikes me as being fearless; she writes of all truths, and in such ways our eyes are reopened to what essentially matters both to a human and a Bene Israel Indian woman. Without knowing her heritage, I was reminded of how “Jewish” this trait is; to question and find oneself through inquiry and self-searching. As I have come to know Joseph through her writing, I can see the breadth of her experiences in multiworlds and how this has furnished her fine mind when addressing the historic contextualization of her people. The sensory evocation of “home” is especially relevant when you consider that for these Jews, home was the hearthplace of their faith as well as their ancestors, the two inextricably linked, lost through time and somehow regained:

he drew maps drew diagrams in his

own hand

and talked of Cairo and Alexandria

the friends he made

where are they now

my third eye is the unsleeping captain

of the dark

purple ink turns brown

writing fades. (“Leaf Boat”)

In “Leaf Boat,” an epic poem, the history and actual smell, color, and texture of the past is pulled from history and made real again. Like a Golem, it stands undisputed, inheriting the modern world with its rich history, one I have heard similar stories of from my grandparents. A story told to Joseph by her father, claimed over time again, is now immortalized in Sweet Malida, for future generations to inherit. What greater purpose has a writer than to uncover and protect knowledge for others?

Candice Louisa Daquin

Grasse, France