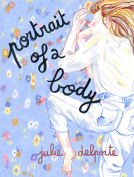

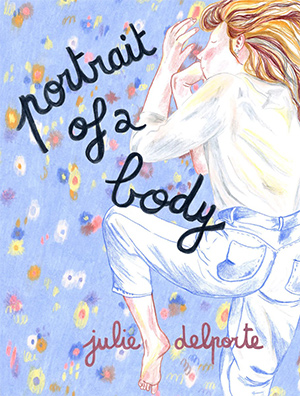

Portrait of a Body by Julie Delporte

Montreal. Drawn & Quarterly. 2024. 268 pages.

Montreal. Drawn & Quarterly. 2024. 268 pages.

Montreal-based artist Julie Delporte has made a name for herself with a body of graphic memoirs drawn in her signature colored-pencil motif. Through tender, heartbreakingly beautiful pencil drawings and text rendered in soft, curly cursive script, the French-speaking writer explores such weighty topics as identity, belonging, and the role of women and women artists in society.

Now her latest work, Portrait of a Body (Corps vivante in the original French), has been translated into English by Helge Dascher and Karen Houle and builds on a literary and artistic foundation combining the qualities of graphic novels, diaries, memoirs, and prose poetry. In intimate discussions and disclosures, the graphic memoir deconstructs sexuality and the expectations often thrust upon young women in our society.

These topics hold a particular relevance for Delporte, who has used her books as a public diary of her sexual evolution. And without spoiling a central premise of the book, one can safely say this new work is the culmination of a journey. It’s also rife with searing revelations. “Since forever, my physical body, this tangible point of contact with the world, has represented the possibility of assault,” she writes. “No wonder I dissociate.” Her attraction to men, which dates back to her teen years, comes in for novel scrutiny. “Sex was something I did to be loved. It was the price I paid for a bit of affection,” adding that rather than eroticize men, she would “fall for them the way you fall for a sofa in a Nordic furniture catalogue . . .”

Delporte is testifying to the complexity of modern life, and she is frank about how she’s been poorly served by people and institutions. This work, however, isn’t depressing. Indeed, for serial readers of Delporte’s work, the book represents a key, liberating chapter in what could be described as a lingering saga of uncertainty. The forty-year-old author of This Woman’s Work and Everywhere Antennas gives voice to the unsettling ambiguity at the heart of what it means to be human.

In previous books, Delporte often covered each page with dense drawings, leaving very little white space. You could argue the anxiety she chronicled in the text spilled over into the drawings on the page, which were busy with figures, scenes, homages. In this new book, that’s not as much the case—her serenity is manifesting itself in more blank space. The drawings, of course, remain singular and exquisite. Here she lingers on imagery evoking flora and fauna while in previous books, the drawings depicted people and places more often. It is reminiscent of much of Georgia O’Keeffe’s most celebrated works of art, and the southwestern American artist is very briefly referenced on the title page. Gorgeous textiles, thankfully, remain a focus of her pencil, and some of the most striking images in the new book are of clothing. One of the boons of reading Delporte’s work is that her books are like scrapbooks that report on her artistic influences and the works of art she is absorbing while creating ones of her own. She revisits her interest in the Finnish comic strip author Tove Jansson, who had an immense influence on Delporte and whose work is explored in greater detail in previous Delporte books. She also references the French author and Nobel laureate Annie Ernaux, whose work has been praised for opening up new avenues and modes of expression, especially to women authors. Here Delporte comments on something that was said of Ernaux: that she’d read too many novels. Delporte pleads guilty to the same.

In a prose-only novel or memoir, these references would consist merely of words. But in a graphic memoir, the author is free to illustrate this influence. In the case of Jansson, for example, Delporte creates drawings that mimic Jansson’s style. It’s testament to so many things—Delporte’s fertile imagination, the richness of the graphic novel/memoir genre, and so forth.

Delporte, a fascinating artist, bears witness to the richness of Montreal’s literary scene and is a model for any writer aiming to take readers on a multisensory, sentimental journey.

Jeanne Bonner

West Hartford, Connecticut