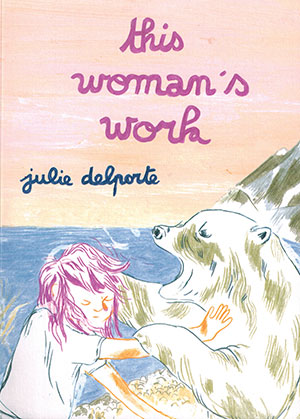

This Woman’s Work by Julie Delporte

Montreal. Drawn & Quarterly. 2019. 256 pages.

Montreal. Drawn & Quarterly. 2019. 256 pages.

The first thing you notice about This Woman’s Work is the image of struggle on the cover—a girl pushing away a polar bear—a metaphor that is investigated more fully within. Next come pages of evocative line drawings awash with color in a slightly muted yet rich palette. The text is intimate and self-revelatory and takes the form of a journal, but if this is a diary of sorts, it is one that is informed by a much larger arena than the self: that of the role of women and especially women artists in a world that privileges men.

Julie Delporte is a French-speaking artist and writer whose work is steeped not only in her own experience of being an artist but in her perceptions and reading of women artists through time. This book was originally intended as an exploration of Tove Jansson, the mid-twentieth-century Finnish artist and writer best known for creating the Moomins, a family of trolls whose adventures are adored by children. But the narrative evolves with Jansson as not the subject but as an inspiration for Delporte as she travels in Jansson’s footsteps to Finland and Greece. In fact, the essence of this graphic memoir is the quest for a role model, a woman artist who is not tied to the male gaze. Hence, there are cameo appearances by Chantal Akerman, Geneviève Castré, and an homage to Kate Bush, whose song gave the English translation its title, as well as images drawn in the style of Mary Cassatt and other women artists.

Delporte’s struggle with her male partners, her own self-confidence as an artist, her early sexual trauma, and her fear of motherhood come to some resolution with a dream of women who live communally and raise orphan girls. But it is, of course, a fantasy, and Delporte must come back to the real world where she ends as she begins, with a fear of pregnancy. There is anguish here as well as a good deal of naïveté, as befits a young woman for whom a large question seems to be whether a man would be able to live with a feminist. Of course, we are informed by our language, and, as Delporte notes, in her native French the masculine always takes precedence over the feminine. The book is beautifully drawn, charming, and often moving, yet in many ways it lacks the depth that would elicit higher praise.

Rita D. Jacobs

New York City