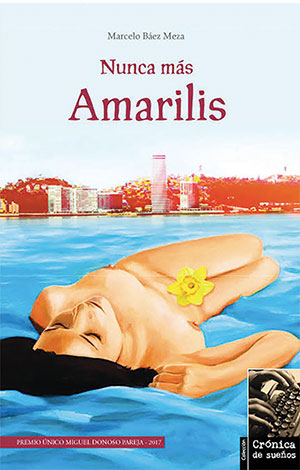

Nunca más Amarilis: Bioficción definitiva de Márgara Sáenz by Marcelo Báez Meza

Quito, Ecuador. Libresa. 2018. 254 pages.

Quito, Ecuador. Libresa. 2018. 254 pages.

This roller coaster of a “biofiction” is a report to an academy that is more Bolañesque and an escape from institutionalized literary constraints than a Kafkaesque performance about human transformation. The kernel for its careful reimagining of how to novelize an un-Churchillian “riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma; but perhaps there is a key” is a truthy story about the apocryphal Ecuadoran poet Márgara Sáenz and the literary mischief surrounding her paper life. Were this work published in a Spanish-language publishing center instead of by a national press in a “peripheral” country with a purportedly small or minor literature, this award-winning novel would attract translations and greater accolades, considerations that Nunca más Amarilis textualizes indirectly.

The objective is not settling scores with a literary domain (predominantly Peruvian and Ecuadoran) that is more and more a parody of itself but an analysis of authorial evasions. Márgara’s initial words are “Be careful with the people you invent because it can turn out they exist.” Many do in the forty-three sections that make up the novel, as do names known to national and international audiences; while others are taken from fictions by canonical authors (in one of her appearances, J. M. Coetzee’s Elizabeth Costello meets Sáenz at a Guayaquil book fair) or critics. Underlying that trans-historical scaffolding is a searing critique of the abandonment with which authors—like the ones of the real anthology Poemas de amor erótico (1972) through which Sáenz came to life—assume their irresponsibility, condemning subsequent critics and readers who take hoaxes to be truthful.

To substantiate that she is not the invention of the poets who compiled that anthology, or the author of the poem “Otra vez Amarilis” attributed to her, Sáenz contends that hers is a definitive “biofiction,” conscious that in cyberspace the poem is better known than she. To set the record straight, she questions the limits of scholarly attention by minutely examining her reception as “the most famous Ecuadorian poet of all time,” which is, of course, the real fiction! Drawing from major and minor prose genres, adding six narrative “biobibliographical chronologies” that fuse real and imaginary items, Báez Meza shows that the rule of deception is that there are no rules in an era of post-truths and fake news.

If one reads Nunca más Amarilis as a vindication, Saénz dislikes Amarilis (an appellation associated with determination and strength) because of the travails she has undergone at the hands of powerful male literary types, providing Báez Meza a reason to document various problems of Latin American literature’s unreliable narrators from the perspective of women—i.e., Cortázar through Edith Aron, Borges through María Kodama. Other critiques take not too subtle spins, as when Márgara pinpoints how Miguel Donoso Pareja, a minor Ecuadorian novelist and progressive critic, “corrected” Bolaño’s acerbic fictional portrayal of him (and supposed grammatical and syntactical errors) in The Savage Detectives, making the pettiness of social- realist writers stranger than fiction. World literature is also present in the larger connections, as in the brief “Historia universal de la impostura metatextual.”

Uproarious precursors—like Augusto Monterroso, Julian Barnes, Bolaño, and Alejandro Zambra’s Multiple Choice come to mind—in the section “Examen del Primer Parcial Literatura Ecuatoriana IV,” a mock examination in which all questions and answers have Sáenz as a protagonist. Bolaño’s modus operandi is now vital to Latin American authors of Báez Meza’s generation and to assorted millennials. He is well aware that the avatars of autobiografiction quickly become their own literature of exhaustion and, with that in mind, has sought novel ways of renewing the twists and turns of contemporary narrative structure, which include lists, as in other world literatures. To parody academic discourse, Báez Meza had to know it well, and his enthusiastic research for doing so is evident.

It is no coincidence that many Latin American prose writers now filter delicate subjective experiences through the prism of illusory characters to partake of the cultural history shaped by mass media and the institutionalization of talent. Yet, allusive on just about every page, Nunca más Amarilis can be a contrarian wellspring for affect theorists, for Márgara’s world (the first

biobibliographical chronology is all about her) is not shaped by atmosphere, mood, or structures of feeling but by unsentimental acts that the hoaxes of literary patriarchy studiously impose on her life and achievements. This counternovel is ultimately a taxonomy of the ethical boundaries of authorship, deftly drawing readers to larger questions.

Will H. Corral

San Francisco